Australia’s flesh eating bug requires urgent research

You might mistake it for an innocuous insect bite – a small painless lump on your arm or leg. But within weeks it’s eating away the skin and tissue underneath, and unless treated with strong antibiotics, it could grow into a gaping ulcerated wound that may take a year to heal and even need surgical reconstruction.

It is the Buruli ulcer, a rare tropical disease caused by bacteria related to leprosy and tuberculosis. But in parts of Australia’s temperate south eastern Victoria state it is now neither rare nor tropical.

Localised outbreaks in the Mornington and Bellarine coastal peninsulas south of Melbourne are suddenly at epidemic levels with 275 new infections in Victoria last year. And scientists have no clear idea of how people are catching it.

“We are now in an urgent situation where we have a huge scientific gap that we need to fill,” says Associate Professor Daniel O’Brien, a clinician and researcher on the frontline treating the disease. He is now leading the call for urgent research into how to prevent it spreading and infecting more people.

Rising infection and severity

A few years ago, Associate Professor O’Brien was typically treating about 10-30 cases a year. In 2017 he saw 110. And the cases are becoming more severe.

“This is a terrible disease that is just getting worse, but how do I tell people how to avoid it if I can’t tell them how they are catching it in the first place?”

He knows of one family who simply fled the area after one of their loved ones contracted the disease.

“We have lots of ideas and theories but it is now getting out of control,” says Associate Professor O’Brien, an infectious disease expert based at Geelong Hospital’s Barwon Health and the Royal Melbourne Hospital. He is also an honorary researcher at the University of Melbourne. “If we are to design effective prevention strategies and health messages, we need answers now.”

In an article published in the Medical Journal of Australia (MJA), Associate Professor O’Brien and colleagues are calling on Australia’s federal and state governments to respond to the epidemic with immediate new funding for research into where the bacteria lives and how it spreads.

The Buruli ulcer (also called the Bairnsdale or Daintree ulcer in Australia), is associated with wetland and coastal areas and there are theories that it spreads into new areas through infected water, possibly via irrigation and flooding.

There is evidence that human-to-human transmission can’t occur, but exactly how people become infected is still unclear. There are suggestions the bacteria might be breathed in, or that it invades the skin through cuts and insect bites.

There are also theories that insects like mosquitoes might carry it and that animals, possibly possums, may act as hosts. In 95 per cent of cases, infections occur in people’s arms or legs, which suggests that insect bites and/or environmental contamination plays a role.

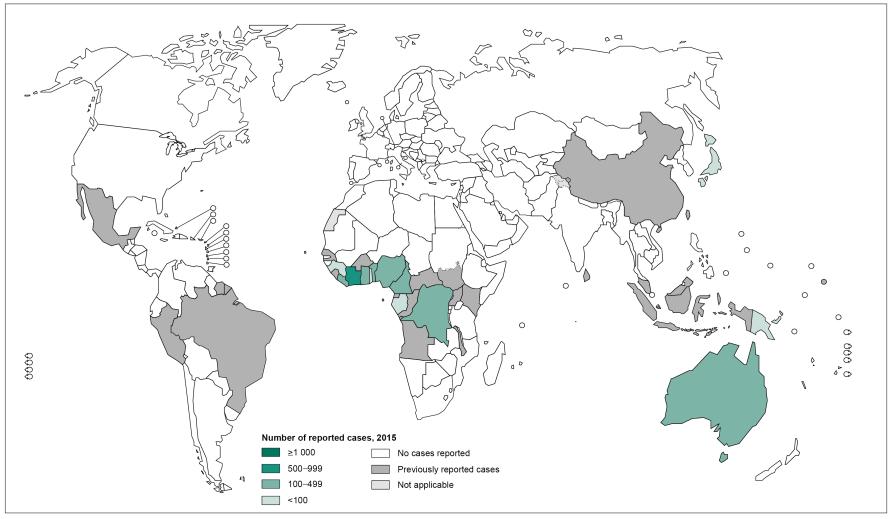

Globally about 2,000 people are infected with the disease every year, mostly in West and Central Africa, and in most affected countries the incidence is declining. But in Australia it is getting worse.

The global distribution of Buruli ulcer in 2015. Infections are concentrated in central and west Africa, but Australia is one of the few places where the number is rising.

In 2016 the number of new infections in Victoria jumped by 72 per cent to 182 and increased by a further 51 per cent in 2017. While some infections occur in tropical parts of Australia’s north and occasionally elsewhere in the country, the great bulk are appearing across these two adjacent temperate peninsulas in Victoria.

And this disease isn’t new to Australia.

The bacteria was first diagnosed in Victoria in the 1930s in the Bairnsdale area on the south east coast. It later emerged in the Bellarine Peninsula, but as recently as 2012 it spread to the nearby Mornington Peninsula.

Curable but traumatic

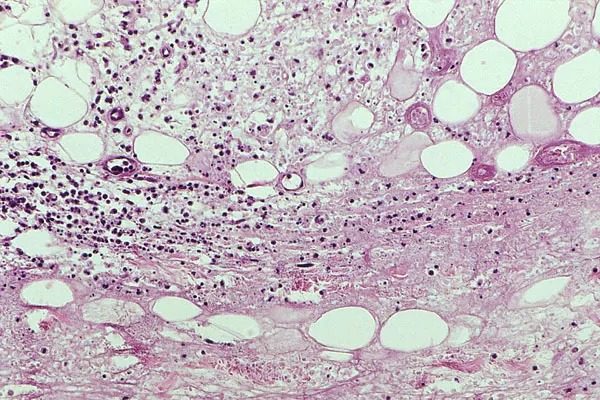

The bacteria that causes the disease mycobacterium ulcerans, is a particularly “nasty and clever” one, says Associate Professor O’Brien. It produces a toxin that not only kills the skin, it suppresses the immune system and contains an anaesthetic that means the initial infection is often painless and can go unnoticed.

The good news is that it is readily treatable, and the need for amputation in severe cases is very rare. However, the cure and recovery can be highly traumatic. The antibiotic treatment takes two months and comes with significant possible side effects such as inflammation of the liver, rashes, nausea and diarrhoea. It can take six months to a year for serious wounds to heal, and surgery and rehabilitation is needed in severe cases.

“Overall a patient faces significant psychological and material costs, so prevention is very much better than the cure,” says Associate Professor Daniel O’Brien.

In the MJA, he and his colleagues write that the direct and indirect cost of treating each infection averages about A$14,000, and that the total cost of the disease in Victoria in 2016 was likely more than A$2.5 million.

Key Questions

They argue that urgent research is needed to analyse soil, water, insects and animal excreta as well to measurement population movements, housing developments and landscape disturbances.

Genomic sequencing of the bacteria is also needed as part of a molecular analysis that could shed light on what factors make the bacteria more virulent.

In particular, they argue there are six key research questions that need to be answered:

-

- Where does the bacteria natural live and multiply?

- How is it transmitted to humans?

- What role do animals and insects play?

- What environmental factors allow the bacteria to grow?

- Why is the disease spreading into new areas?

- Why are cases becoming more severe?

For Associate Professor O’Brien, he’s now gone past his 500th patient with the disease, and he says the time for just focusing on treatment is well and truly past.

“It has always been a neglected disease in terms of research, and it is a complex one that needs resources if we are to understand it. Until recently it had been highly localised with few cases so there hadn’t been an urgent need investigate it in detail.

“But we are now facing a worsening epidemic and we lack the knowledge and tools to address it. We’ve haven’t got time anymore, we need action.”

This article was published by Pursuit.