On a computer in suburban Melbourne, hundreds of tiny dots flicker and jump off an otherwise muted screen. On the face of it, it’s just a pretty image, but in fact each sparkling pixel represents a snapshot of humanity – Ukrainian people tapping into a lifeline; the internet.

At 5am on the 24 February, Russian forces began their invasion of Ukraine and, although some 14,000 kilometres away from the unfolding crisis, a team of researchers from Monash University immediately began analysing the impact.

Day and night since, Associate Professor Simon Angus and his team at the Monash IP Observatory have been analysing the impact of the Russian invasion in real time, and every illuminated speck provides precious data that gives an invaluable insight into the embattled nation’s internet usage and connectivity; the connection Ukraine maintains to the outside world.

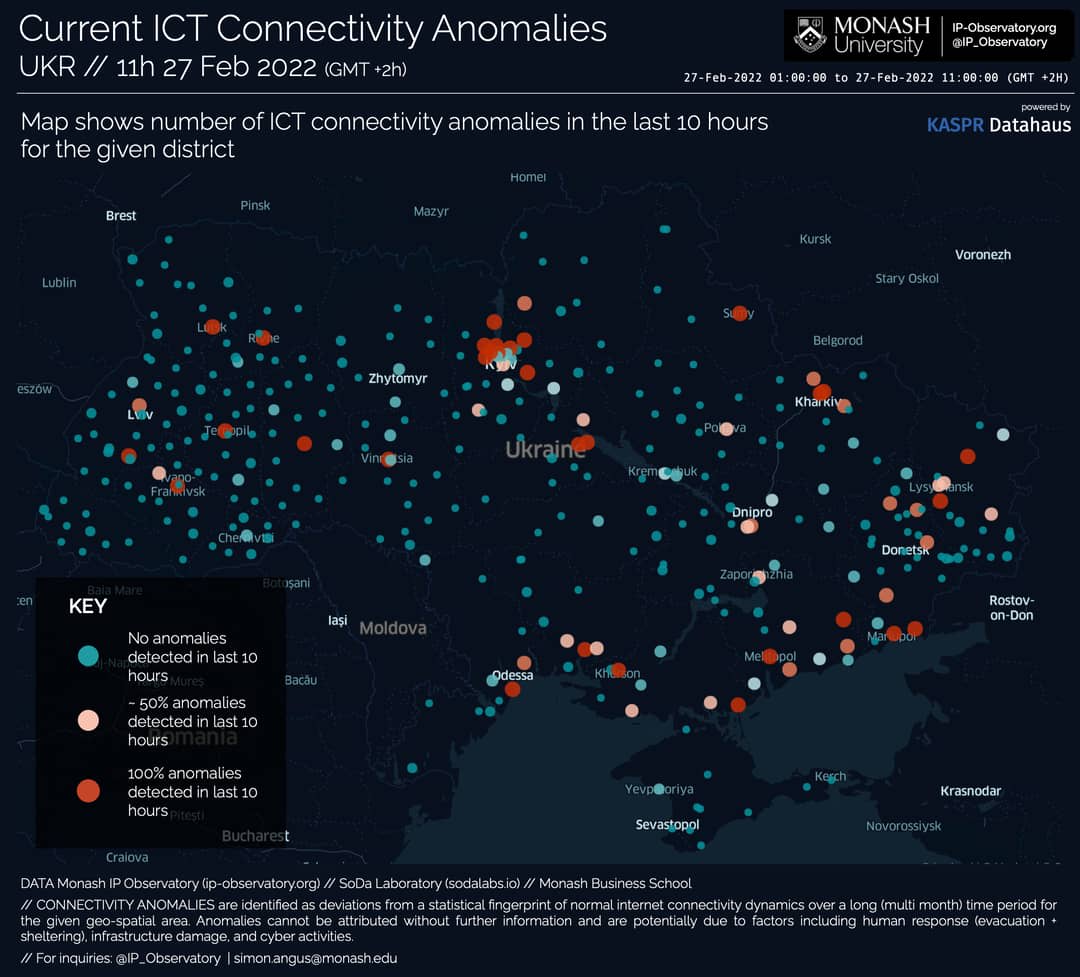

“So far, the Ukrainian internet is holding up. After the initial shelling, several districts within the major cities of Kyiv and Kharkiv experienced a sudden drop in their connectivity, but there’s been only a few major drops since,” says Associate Professor Angus.

“Over the first weekend of invasion we noticed gradual reductions of between 10-25%, most likely due to human behavioural changes, such as people sheltering, evacuating and not being online at fixed broadband locations such as their homes or offices, but these have stabilised and remained remarkably steady since.

“However, it’s likely that a shift in the offensive strategy by the Russian military, as analysts predict, to more intensive artillery shelling of the main cities, will result in further sudden drops of connectivity as infrastructure is damaged.

“We’ve seen this in Mariupol, which has been effectively offline since the early hours of the 2 March after the Russian shelling destroyed all electricity, heating, and water infrastructure.”

The Monash IP Observatory is a global research platform that remotely measures 400 million unique internet addresses in 20,000 district-level regions globally, and can observe the activity and quality of the internet at any location around the world at any given time. The technology behind the observatory has also been commercialised and licensed to a Monash spin-off, KASPR Datahaus Pty Ltd.

Since its inception four years ago, Associate Professor Angus and his Monash Business School colleagues Professor Paul Raschky and Dr Klaus Ackermann have been collecting data on critical world events as part of a unique global research project that seeks to understand the impact of human behaviour using internet activity.

They’ve previously monitored world events such as the 2018 Russian presidential election, the Hong Kong protests, the Puerto Rico earthquake in 2020, and most recently, the impact of the Tongan volcanic eruption.

Right now, their focus is on the unfolding crisis in Europe, and they’re monitoring the Ukrainian internet around the clock. Communications and connectivity, the ability for Ukrainians to access information and share on-ground information with the world, is a vital weapon in the battle for the country’s freedom. Alarmingly, Associate Professor Angus says it’s possible for Russia to completely shut down the Ukrainian internet, the effects of which would be devastating.

“If the Russians overtake the entire country, then yes, they certainly could,” he says.

“This is a major concern. In our experience of observing shutdowns in times of political turmoil such as Myanmar, shutdowns are typically the pretext for atrocities against civilians.

“An internet shutdown delays or extinguishes the opportunity for eye-witness audio and footage to be shared outside the country. Right now, the United Nations Human Rights Council is developing a resolution on internet shutdowns and their role in human rights violations.

“Keeping the internet up in Ukraine is vital both as a deterrence and a means of accountability and justice.”

History repeats: Propaganda and war in the past

The suppression of information and the spread of propaganda was a key tool used by Hitler during World War II.

He created the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, which handed out daily instructions to all German newspapers, Nazi or independent, on how the news was to be reported.

Hitler’s preferred method of communication was radio, because he knew he was a persuasive orator and he used it to great effect, with Germans gifted millions of radios to tune in to the 11 hours of Nazi programming each day. Joseph Goebbels called radio the eighth wonder of the world for its ability to promote the Third Reich.

By contrast, across the border, Polish citizens who were suffering shocking atrocities were banned from listening to the radio, a crime punishable by death, and had little means of communicating news of their worsening plight to the outside world.

As this current crisis unfolds, Russia has adopted laws that make the publication of “false” or “mendacious” information about the military, such as reporting atrocities in the Ukraine, punishable by up to 15 years in prison. History repeats.

There’s no doubt that the current mass of real-time content streamed around the world by Ukraine’s citizen reporters has united and galvanised the world’s response.

Live broadcasts of bombings, images of the injured and women and children sheltering in bunkers, has rallied global leaders.

If connectivity is impacted, the world will immediately know about it, thanks to the work of the Monash IP Observatory.

“Russia has continued to invest in its disinformation strategies. It’s most likely to consider the internet an instrument of state control and keep it on, but embark on major filtering and disinformation efforts,” says Associate Professor Angus.

“However, if they see the internet as too much of an informational risk, they could seek to shut it down immediately. This would be a sign that they’ve lost control of the informational environment, or more darkly, a sign that they’re about to embark on a major round of devastating attacks on civilians.

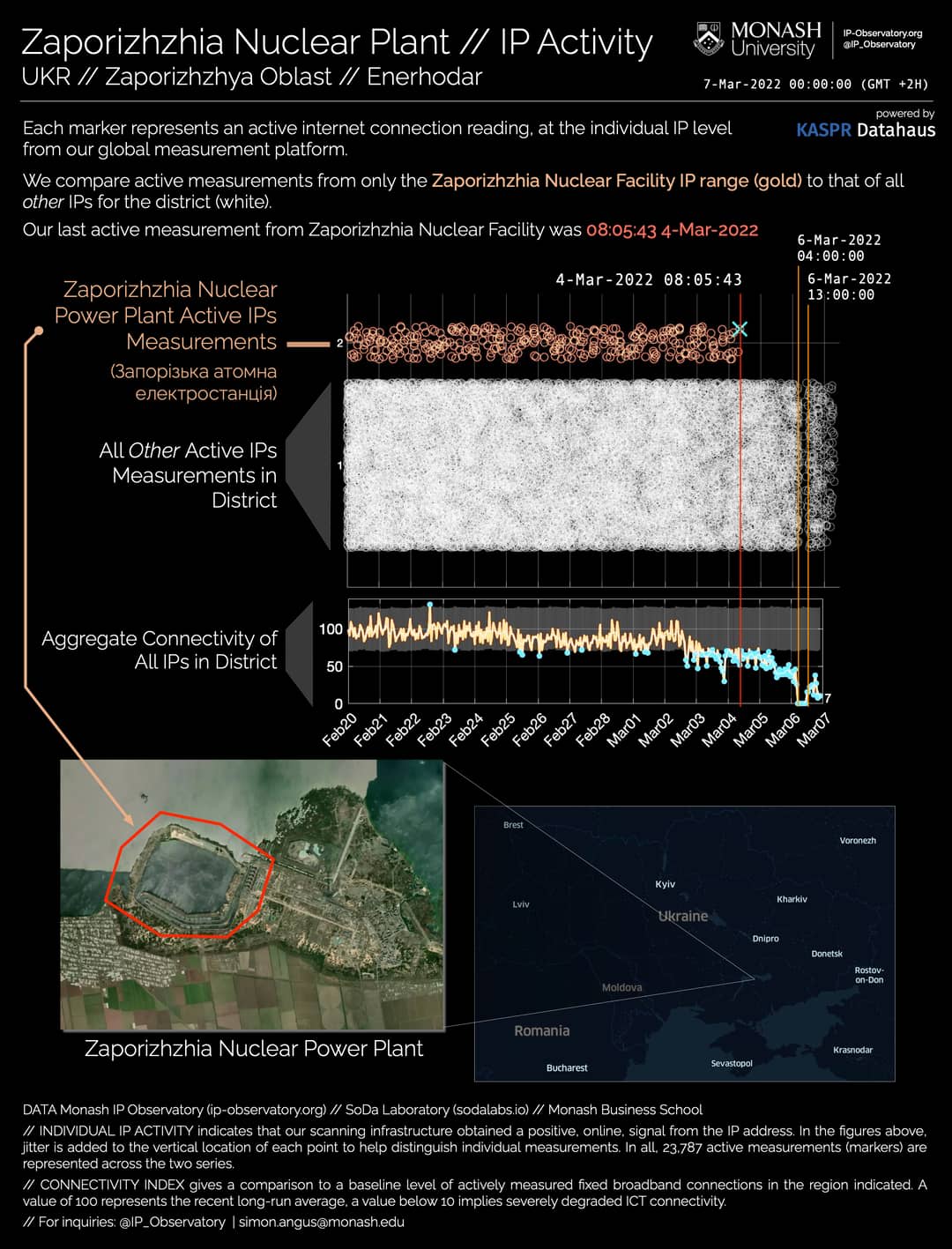

“Perhaps the most worrying sign has been the evidence we’ve found of the first highly targeted shutdowns. For example, the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the biggest in Europe, was attacked by Russian forces, and set on fire, during the 3 March attack.

“We’ve analysed our consistent measurements of the plant’s internet connections and saw them disappear completely on 4 March at 8.05.43 in the morning; – and none since.

“Since we continued to see active internet for locations very near the plant, the evidence points most strongly to the Russians intentionally disconnecting the plant itself from the internet.

“This is a major issue for all of Europe, and the world, as each nuclear facility is required to report continuously their operating data for the IAEA to monitor.

“This is reckless by Russia, endangering our people and planet well beyond the conflict zone,” he said.

How will Ukraine keep SpaceX’s Starlink internet service online?

Keeping the ground terminals powered is becoming increasingly problematic. #UkraineRussianWar #Ukraine #Starlink— George Thomas (@FordPrefect747) March 4, 2022

Right now, Ukraine remains well-connected to the world and has received additional support from Elon Musk, who delivered hundreds of StarLink internet terminals that provide internet connection via a constellation of low-orbit satellites.

“This will be an important backup for Ukraine to stay online,” says Associate Professor Angus. “One StarLink terminal means one internet connection, but a small local network could be created off these. And there are some risks – such as the communication signature providing a target for bombing, but experts online have been quick to provide support to Ukrainians to mitigate these risks. StarLink is a small but potentially important contribution, depending on how the invasion unfolds.”

This article was written by Simon Angus, an Associate Professor in the Department of Economics of Monash University, Paul Raschky, an Associate Professor of Economics; and Klaus Ackermann, a Lecturer in Econometrics and Business Statistics at the same institution. It was published by Lens.