DFAT’s budget squeeze damages Australian interests

Our research, published in Australian Foreign Affairs, shows that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is now at a new low point at just 1.3 per cent of the total federal budget.

DFAT funding is at a new low point of just 1.3 per cent of the total federal budget.

This is a long-term trend across Australian governments over more than a decade. In the last five years, DFAT has been a particular target for cost-cutting with reports that at least 25 per cent of the cuts across government have fallen on this one department.

This might not be a problem for Australia if the world were getting easier to deal with. But it is not.

In a speech this month, Prime Minister Scott Morrison eloquently described “the new and challenging world that Australia faces” with a new economic and political order still taking shape.

He listed challenges including “a new era of strategic competition”, technological disruption, dependence on global trade, automation, artificial intelligence and continuing security threats from terrorism, extremist Islam, anti-Semitism, white supremacism and “evil on a local and global level”.

This suggests that it’s not the time to be reducing the ability to grapple with these challenges.

Again, the cuts to DFAT might make sense if there were cuts across the board. But these cuts have not been mirrored in other areas such as defence and intelligence.

In the two decades since the 9/11 attacks, from 2001-02 to 2019-20, the Department of Defence budget has increased by 291 per cent, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation has grown by 528 per cent and the Australian Secret Intelligence Service by 578 per cent.

Australia is investing way too little in the core national interest of influencing the world beyond our shores.

To give a sense of the scale involved, Australia’s 2019–20 combined defence budget at $A59 billion is more than nine times the combined budget for diplomacy, trade and aid at $A6.7 billion.

In our research, we benchmark what would be a reasonable investment in foreign affairs to promote Australia’s interests in the world.

One option is to compare Australia to other developed countries with similar-sized economies such as Canada, which spends 1.9 per cent of its national budget on diplomacy and aid, or the Netherlands which spends 4.3 per cent.

Arguably Australia should invest more than these countries, as it is located in a more turbulent region.

Another benchmark would be the last time that Australia faced a similarly challenging world: after World War II, when a new global order was being built.

In 1949, the combined diplomacy, trade and aid budget was almost 9 per cent of the federal budget compared to the current low of 1.3 per cent.

All of these benchmarks suggest that Australia is investing way too little in a core national interest: influencing the world beyond its shores.

To change this thinking, we need to make the case of what diplomacy gives us: a way to influence the world.

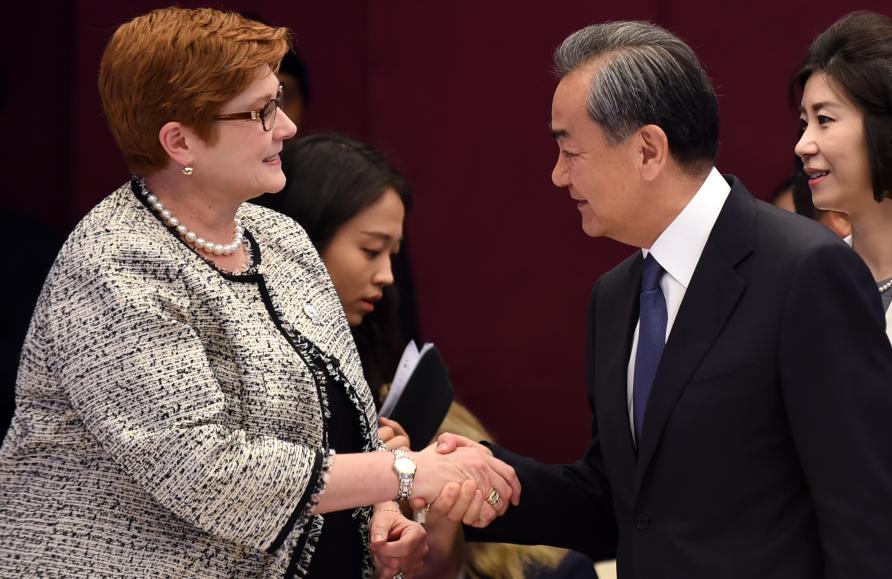

Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne meets China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

Diplomacy helps make us safe against threats: whether it is cooperation on global pandemics, coordinated action against international crime or competition for influence to promote our values.

It helps our economy by assisting business to access new markets, providing the space to build relationships with potential investors and showcasing Australian products to the global marketplace.

Diplomacy is about creating a more favourable world for Australia’s interests.

The Prime Minister has explained clearly how what happens internationally affects Australians:

“Whether directly or indirectly, these changes impact Australians. On our jobs, what we earn, our living standards and the essential services we rely on, that depend on a strong budget and strong economy…

“On our environment… On our safety, that depends on our national security, afforded by our alliances, our defence, diplomatic and intelligence capabilities, our adherence to the rule of law and our ability to enforce the law.

“On our freedom, that depends on our dedication to national sovereignty, the resilience of our institutions, and our protections from foreign interference.”

Diplomacy is about creating a more favourable world for Australia’s interests.

In the words of another prime minister, Kevin Rudd: “Given the vast continent we occupy, the small population we have and our unique geo-strategic circumstances, our diplomacy must be the best in the world.”

We can’t get the best diplomacy with bargain basement investment.

Voters need to understand the cost of failing to invest in the tools to project Australia’s national interests, to convince governments of the future that DFAT isn’t an easy target when there are cuts to be made.

This article was written by Melissa Conley Tyler and Mitchell Vandewerdt-Holman of the University of Melbourne. It was published by Pursuit.

Melissa Conley Tyler is a Research Fellow at the Asia Institute in the University of Melbourne.