Praising what is lost makes the remembrance dear

Our understanding of Shakespeare benefits from appreciation of the plays that he was responding to and influencing in the repertories of the London-based companies, but most of the play-texts from those repertories have been lost.

Recent estimates suggest that for the period of 1567 to 1642, while only 543 plays from the London commercial theatres have survived, as many as 744 plays are identifiably lost, with hundreds more completely untraceable.

Surviving plays constitute the distinct minority of the total dramatic output for the period.

The advent of the Lost Plays Database in 2009 and the publication of instalments of Martin Wiggins’ multivolume Catalogue of British drama (since 2012) have been instrumental in making this information available. But what can be done with all this new knowledge?

Plays become lost for a variety of reasons and appeals to ‘quality’ as the basis of non-preservation are not genuine explanations: without comparative data, ‘quality’ is unmeasurable.

Unfortunately for us, the great variety of causes of loss means that the surviving drama is, statistically speaking, atypical precisely because of its survival; these plays constitute the distinct minority of the total dramatic output for the period.

Unpredictable and arbitrary causes including fire and vandalism, for example, are responsible for the loss of a large number of play-texts.

John Warburton (1682-1759) notoriously claimed that his invaluable collection of unpublished play manuscripts was lost through the callousness of his cook Betsy, under whose care “they was unluckily burnd or put under Pye bottoms”.

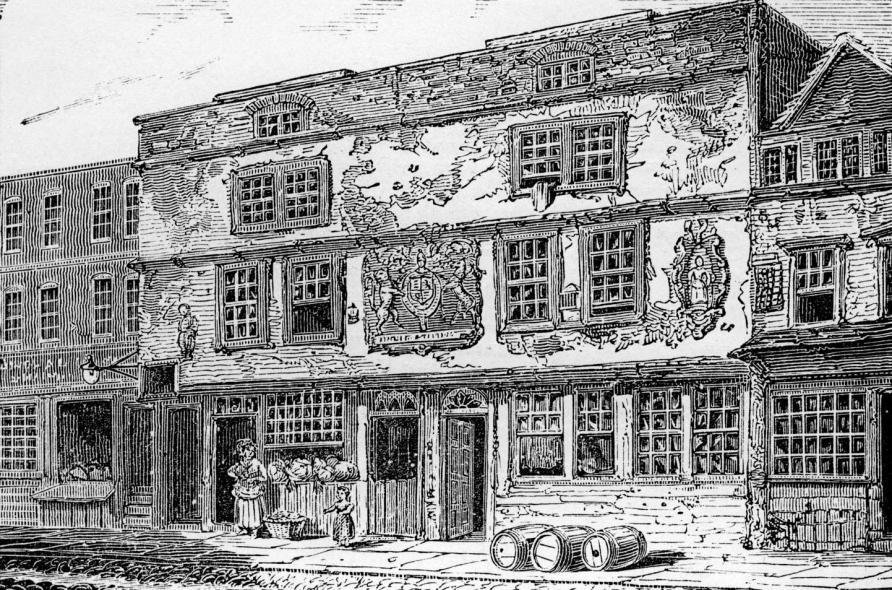

The tragedies that befell the playing companies who occupied the Cockpit and the Fortune playhouses are less contentious, in that they demonstrably did occur.

On Shrove Tuesday, 1617, the Queen’s Men became the victims of the riots accompanying what was the traditional holiday for apprentices.

Thousands of rioters took to the streets, some of them breaking into the Cockpit theatre in Drury Lane and (as one contemporary letter-writer reports) “cutting the players apparell all in pieces, and all other theyre furniture and burnt theyre play books and did what other mischief they could”.

The Fortune playhouse was burnt down in 1621, taking all of its plays with it.

The immolation of the Fortune playhouse in December 1621, in which all the “apparell and play-bookes” were lost, likewise struck a significant blow to the survival rate of plays in the repertory of the Palsgrave’s Men.

Censorship has also played a hand in the loss of drama. Most famously, performances of Ben Jonson and Thomas Nashe’s seditious ‘Isle of Dogs’ play (1597) almost brought about the tearing down of playhouses and the suppression of playing across London and further afield.

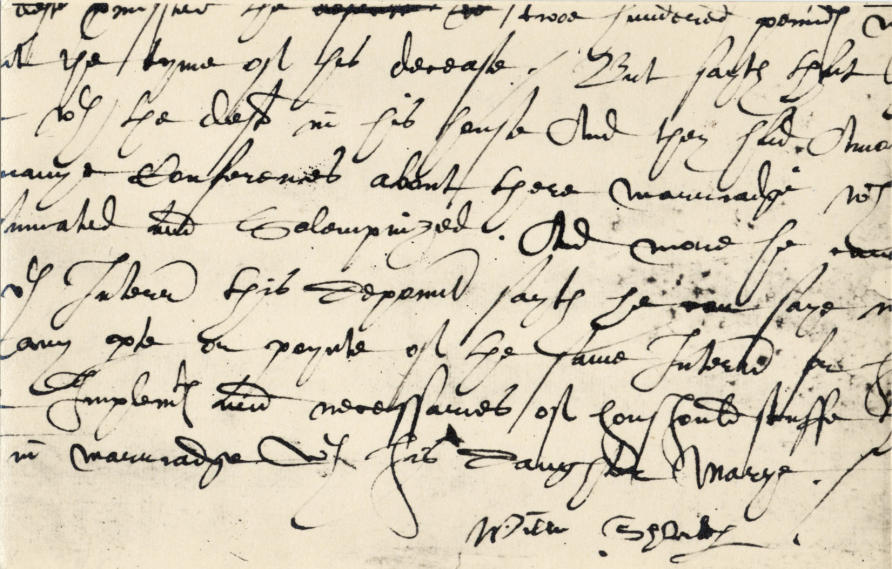

Quite how the play caused offence is a matter of conjecture and dispute. But whatever the supposed offence, the Privy Council instructed the governmental inquisitor Richard Topcliffe to ascertain ‘what copies’ of the play had been circulated and to “peruse soch papers as were fownde in Nash his lodgings”.

Wilful destruction of play-texts also accounts for the loss of some plays.

Sir Fulke Greville, first Baron Brooke of Beauchamps Court, is best known as the author of short poems and Senecan closet dramas including Mustapha (c.1596) and Alahum (c.1600).

He also wrote a play about Antony and Cleopatra, but it perished in an act of self-censorship. In the wake of the failed coup and subsequent execution of the Earl of Essex in 1600, Greville realised that the play he had recently written might be misconstrued as dangerous political commentary.

Fearing the repercussions of such an identification, Greville decided to burn his manuscript himself, even though he maintained that no such allegory was intended. (He likened himself to the Greek philosopher Thales, who was so preoccupied with gazing at the stars that he fell down a well).

Sir Fulke Greville’s play about Antony and Cleopatra perished in an act of self-censorship.

The logistics involved in bringing a play from the stage to the page were also undoubtedly a contributing factor to the loss of so many play-texts.

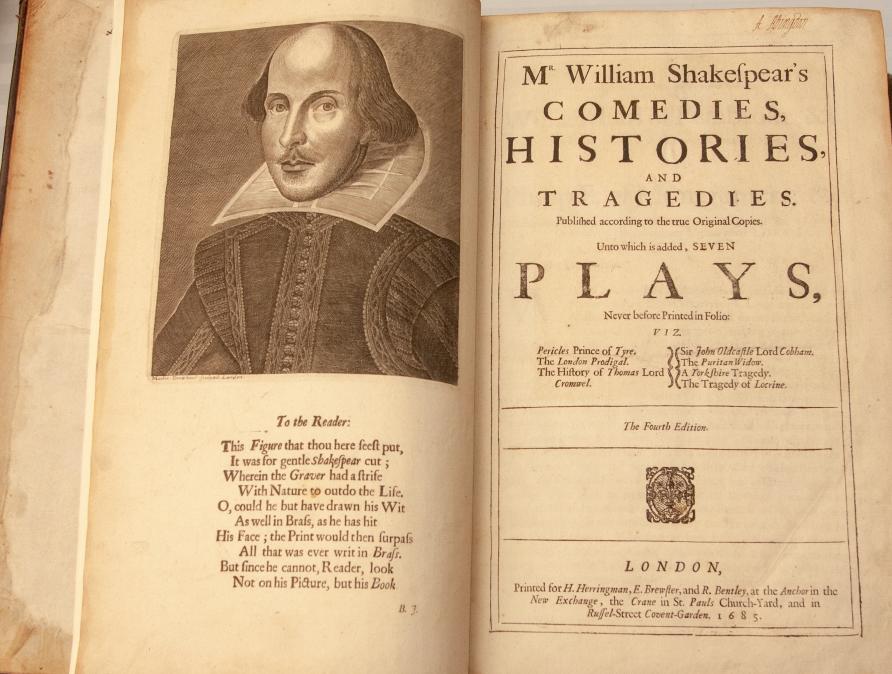

Claims that half of Shakespeare’s plays would have been lost had they not appeared in his First Folio of 1623 are somewhat overstated (presumably attempts would have been made to publish at least some of them in cheaper formats), but it is certainly the case that eighteen plays by Shakespeare appeared in print for the very first time in Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies.

Unlike Ben Jonson, Shakespeare could not assist with the publication of his collected works, having died in 1616.

Play selection seems to have been determined by availability (what the stationers involved in the project already had rights to or could acquire) and perhaps some other principle of aesthetic resembling Jonson’s criteria for folio inclusion.

All is True (Henry VIII), co-authored with Fletcher, was included, but The Two Noble Kinsmen and ‘Cardenio’ (also Fletcher collaborations) were not, and neither was Pericles, co-authored with George Wilkins. ‘Love’s Labour’s Won’, which was apparently in print by 1603, was also omitted.

The plays that were included stem from a variety of copytexts of varying quality: it was not simply the case that the ‘best’ were published.

The ‘mudslide’ of the Folio offers a just cause for celebration, but the process of its creation also helpfully illuminates the various contingencies associated with attempting to preserve plays in print.

Partial list of plays from an inventory. From top: marchant of vennis, taming of a shrew, knak to know a knave, knak to know an honest man, loves labor lost, loves labor won.

The versions of extant plays that survive are not necessarily the most recent, authoritative or any other ostensible index of quality – they might be old or inferior copies that happened to still be available when the Folio editors began their project of assembling Shakespeare’s works.

The above editorial inferences can be supplemented with historical evidence from 1623, the year that the First Folio was printed, when the Master of the Revels had to re-license for the King’s Men “[a]n olde playe called Winter’s Tale’ since ‘the allowed booke was missinge”: the licensed text was not available, but clearly the company had recourse to an alternative manuscript, and the play was printed that year.

Certainly, some early modern readers accorded little value to playbooks.

Sir Thomas Bodley famously classed “Englishe plaies” alongside almanacs and pamphlets as “riffe raffes” and “baggage books” that his first Keeper, Thomas James, should take care not to admit into the Bodleian library (“hardly one in fortie” of them being “worthy the keeping”).

With the central tenets of repertory studies well and truly established, and a gradual elevation in the status accorded to lost plays by critics, it is now possible to do what was unthinkable thirty years ago and focus primarily on lost plays as the context for understanding Shakespeare’s work and the commercial marketplace of the London theatres during his lifetime.

At the same time, it is imperative that we acknowledge that lost plays are lost to us; that we do not assert, over-confidently, what they were about or how they handled their subject matter.

It is now vital to restore lost plays to their natural environment and commercial context alongside the surviving drama from the London companies’ repertories, offering a timely critical reassessment of early modern drama.

The surviving versions of plays were not necessarily the final drafts.

In this book, I approach the question of coping with loss by thinking in pragmatic terms about how scholars can and should incorporate discussion of lost plays into their work on substantially extant texts.

At its heart is my desire to better understand Shakespeare’s plays by restoring them to their most immediate and pressing context: the lost drama of the day, which also constitutes the majority of drama of the day – and thus the most severely neglected yet relevant of all contexts.

This is an edited extract of Dr David McInnis’ new book Shakespeare and Lost Plays: Reimagining Drama in Early Modern England published by Cambridge University Press. The book is available for purchase online. This article was published by Pursuit.

David McInnis is an Associate Professor of Shakespeare and Early Modern Drama at the University of Melbourne. He is author of Shakespeare and Lost Plays and Mind-Travelling and Voyage Drama in Early Modern England.