Learning in the homelands

In the traditional lands of the Yolŋu in Australia’s North East Arnhem land there are a network of small ‘Homelands’ schools, officially called Homeland Learning Centres.

Many Australians may not know about the Homelands Movement. It was initiated in the 1970s and involved the movement of small Indigenous communities back to their ancestral lands. Homeland Learning Centres (HLC) have been established in some of these intentionally and remotely positioned communities.

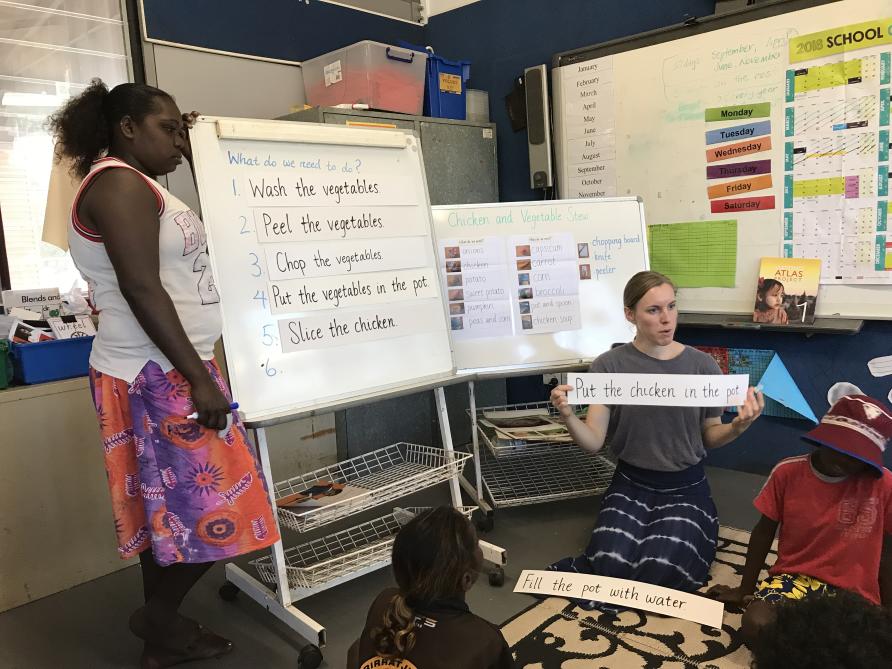

For those teachers visiting the Homelands Schools – there is much to learn.

They travel from the hub community of Yirrkala to HLCs in a light aircraft or 4WD, staying as guests to teach physically alongside Yolŋu educators who live permanently in these Homelands. When the school day is over, teachers will often go hunting or fishing with families – learning about the land they’re on. And it’s here that the tables are turned and power is flipped, as the Yolŋu children become the ‘teachers’ and the teachers become the students, as they share their knowledge.

In Yolŋu communities hunting isn’t just a recreational activity; it’s a time when important intergenerational knowledge is imparted and vital stories of the land are shared. Elders have continually stated that they want non-Yolŋu teachers to learn with families so that they understand the knowledge that students bring to school.

And this sharing is critical in strengthening the practice of both Yolŋu and non-Yolŋu teacher’s in remote Australia.

As educators, becoming learners together is an important part of understanding the context. The generosity of this sharing helps develop an understanding of the students’ worldview, including the linguistic diversity that exists in communities around the country.

University of Melbourne has partnered with Yirrkala Homelands School and the local public Yirrkala School since 2011 to provide selected pre-service teachers with the opportunity to complete a two or four-week, self-funded placement.

For the pre-service teachers privileged to undertake a placement in these remote Homeland Learning Centres, it’s an invaluable lesson in developing empathy, humility and a sense of place. And it works.

There are currently 10 Melbourne Graduate School of Education (MSGE) teachers working in schools in the Northern Territory as a result of this placement program. Recruiting staff to these remote locations as well as retaining them is a chronic problem, so the fact that MGSE teachers return to these remote areas is really something to celebrate.

Indigenous education is a highly political space, often characterised by deficit and theories around gaps that need to be filled.

Often, the conversation in Indigenous education in the NT is dominated by what students, and the remote communities in which they live, can’t do. But we are interested in what they can do.

We can learn from these unique schools and educators. In particular, we need to acknowledge the strength and contribution that this region is making to the development of pre-service teacher education.

To acknowledge strength isn’t to minimise the challenges faced by these remote schools, not the least of which is bridging the language and cultural differences between Yolŋu and westernised teaching.

Neither does it deny the importance of English literacy and other skills that support access and choice. But understanding and building on the strengths of these schools and communities is an important part of addressing these challenges.

For pre-service teachers, the opportunity to learn how to connect with Yolŋu students and their communities, and draw on the resilience and knowledge of Yolŋu educators, is a valuable experience. Understanding this will support their teaching practice throughout their careers wherever they decide to teach.

For many years Yirrkala has been committed to developing learning alongside local Indigenous knowledge systems. These distinctive educational approaches push the boundaries of what pre-service teachers have previously conceived education to be.

As MGSE student Carlo Manley, explained after a four-week placement at Yirrkala:

“I didn’t expect to see so much explicit integration of Yolŋu culture and knowledge and to have planning begin with Yolŋu people and consulting elders on content. Western knowledge is included where and when it’s appropriate – I didn’t even know that this was a thing in Australia. I’m excited by this.”

As another student teacher, Marcus Pedersen reflected after his placement:

“It has taught me to challenge a lot of stereotypes that I didn’t even know I had. In a Melbourne context the expectations I had on myself and the concept of what engaged classrooms look like, you know listening, eye contact, asking lots of questions and lots of writing. Here I’ve learnt about the importance of silence and staying comfortable with the silence”.

This place-based teaching makes strong links, not only with the national curriculum, but also with the locally developed curricula in a way that encourages a student’s identity and knowledge.

Being immersed in this environment and witnessing the depth of learning that occurs through place-based teaching, provides educators with an opportunity to engage in a reflexive practice. Importantly, it helps them challenge any of their own assumptions of knowledge, education and place.

Since 2011, more than 60 students have participated in placements, in rural and remote settings, that includes North East Arnhem Land. Of these, 18 graduates have returned to teach in NT schools.

Crucially, those from the MGSE program who have returned to work in the NT have stayed for longer than two years.

In fact, many are still currently working in remote locations – including Carlo, who has taken a position in a remote NT school and plans on staying there.

In 1969, Australian anthropologist Ted Stanner famously said: “There are perhaps too many, theories about our troubles with the Aborigines. We can spare a moment to consider their theory about their troubles with us.”

Professor Stanner’s words still resonate today. Rather than finding problems with communities, maybe a commitment to strengths-based learning and genuine partnerships would lead to more ‘success’.

It isn’t until you listen, really listen, to the voices of Yolŋu educators who have clearly articulated the vision of education for their children over many years, that you can see the depth of wisdom and vision.

Maybe the answers are located in place.

This article was written by Bernadette Murphy, a Research Fellow at Melbourne Graduate School of Education, Lombiŋa Munuŋgurr a Homeland Centre teacher in Garrthalala and Claire Rafferty, an Educator and PhD Candidate in the National Centre for Indigenous Studies at the Australian National University. It was published by Pursuit.

Bernadette Murphy is a Research Fellow, Lecturer and PhD Candidate in the Youth Research Centreat the Melbourne Graduate School of Education in the University of Melbourne.