The maths and ethics of minimising the COVID-19 toll

Over the weekend, several Australian states announced shutdowns of non-essential activity, including New South Wales and Victoria.

But what’s still unclear is the strategy the Federal Government is taking. There are really just two options.

The Australian Government needs to outline what our country’s endgame is.

An excellent piece published in The Conversation by Professor John Daley of the Grattan Institute argues that we – actually, the Government – need to announce what our country’s endgame strategy is.

Is it audacious and ‘go for broke’?

This means a nearly complete societal lockdown and very vigorous containment (as we’ve seen in Wuhan), with the aim of eradicating the virus from Australia within two to three months. Then keep the borders completely locked until a vaccine is available. This is what Professor Daley calls Endgame C, the ‘stop then restart’.

Or is it ‘flattening the curve’?

This approach aims to reduce harm from the pandemic while slowly building up herd immunity. Professor Daley calls this Endgame A. And it appears this is what most countries are pursuing – but often without clear articulation.

Professor Daley also offers a third option, Endgame B, tracing and tracking every infection, but we think of this as part of the toolkit for Endgames

A and C.

We need to protect our older people and people with chronic disease from coronavirus, but there’s the other side of the coin that we don’t really like talking about.

If we are flattening the epidemic curve, we need our young and healthy citizens keeping critical parts of the economy going and being infected at higher rates to build up herd immunity.

New South Wales, Victoria and other Australian states have announced drastic shutdowns.

But is asking our fit and healthy younger citizens to do this fair? And what is the rationale?

It is a matter of great urgency that governments everywhere, including Australia, announce their strategy; are they having a crack at eradication with ‘stop then restart’ (with its attendant additional level of short-term social and economic disruption, but a flickering light at the end of the tunnel), or keep on ‘flattening the curve’?

But since any eradication strategy might not be adopted or might fail, we still need a good understanding of ‘flattening the curve’ as the comparator.

How many deaths might we have under flattening the curve?

COVID-19 has a reproduction number (R₀) of about 2.5 in society functioning ‘normally’ – it is lowered by social distancing.

For the epidemic to peter out under ‘normal’ societal functioning requires that about 60 per cent of people are infected and become immune (1 – 1/R₀ = 60 per cent).

This is herd immunity – when a higher enough percentage of the population is immune, due to either infection or vaccination, that reintroduction of the virus will not see it able to take hold.

A recent study by Imperial College in the UK estimated that mortality rates among those infected by age vary enormously from 0.002 per cent among zero to 10 years old, up to 9.3 per cent for people 80.

This is a pattern that is consistent with what was reported in a large Chinese study.

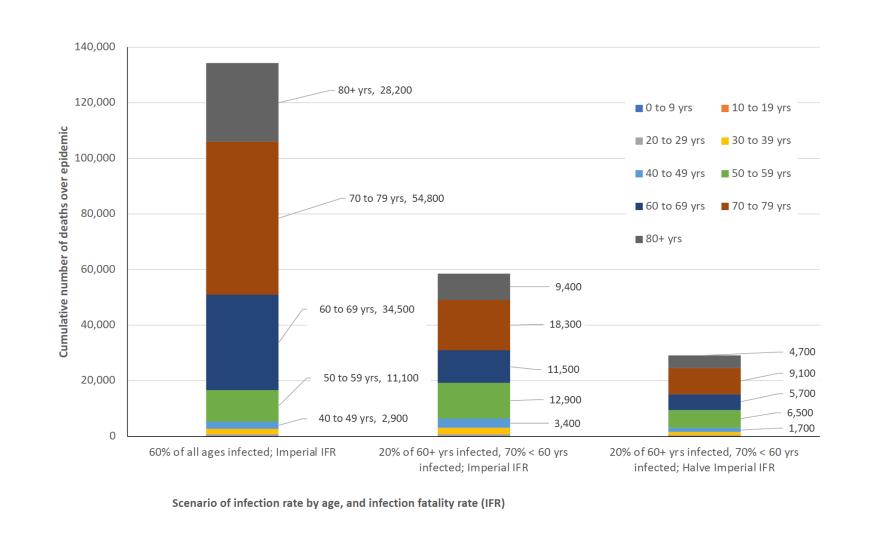

Deaths by age group for three scenarios under ‘flattening the curve’ until 60 per cent of the Australian population is infected.

If by the epidemic’s end 60 per cent of all age groups are infected, this is (a shocking) 134,000 deaths in Australia.

Can we do better than this? Yes.

If we protect, which unfortunately also means ‘isolate’, people over 60 years old really well.

Let’s assume by epidemic’s end only 20 per cent of people over 60 have been infected. The corollary is that 70 per cent of younger people need to become immune through infection to get the average infection rate to 60 per cent to achieve herd immunity.

But this ‘simple’ measure has a profoundly beneficial effect, halving the total number of deaths to 58,600.

Why? Because the 118,000 deaths among the over 60s are reduced to 39,000, with a compensatory increase from 16,700 to 19,400 deaths among younger people.

Can we do better than this? Almost certainly.

Let’s assume that improving knowledge about treatments and healthcare organisation for people with COVID-19 leads to a 50 per cent reduction in the case fatality risk.

‘Flattening the curve’ aims to reduce harm from the pandemic while slowly building up herd immunity.

This is speculative but a lot of re-organisation of healthcare systems is currently underway to improve managing COVID-19 cases which should see reductions in case fatality.

This results in a halving of the number of deaths to 29,000 – approaching the 21,000 deaths per year from tobacco in Australia (although this only serves to remind us how disastrous the tobacco epidemic is, year in year out.)

Can we do better still? Probably.

What has not been factored into the above calculations is that below the age of 60, the majority of deaths occur among people with chronic conditions like respiratory and heart disease.

If we wrap protection around these people as well as those over 60, the death rate will fall further – but again this will rely on young healthy people having high infection rates and becoming immune.

Is this ethical?

Under a health gain maximising utilitarian framework, yes.

So long as the total life years saved by protecting the old and unwell exceed the life years lost among the increased numbers of young people dying – which it likely does.

Improving knowledge about treatments and healthcare is likely to lead to a reduction in COVID-19 fatalities.

There are other ethical and philosophical analyses that could be made – the ‘fair innings’ argument for example that puts more weight on saving younger lives.

But the ‘flattening the curve’ strategy means we are then obligated to consider a societal contract.

If young (and healthy) people are expected to keep working and experience higher infection rates, the small proportion of those young people unfortunate enough to get very sick deserve prioritisation of critical care facilities over the elderly and people of all ages with chronic conditions.

Does this type of analysis help decision-making?

It should do.

Leaders in Canberra have some numbers to inject into this tough decision.

Let’s assume that a ‘stop then restart’ eradication strategy – if successful – still results in 5000 deaths before eradication is achieved.

Assuming about five years of life lost per death (as they will mostly be in the elderly or those with chronic conditions), that is 25,000 life years lost.

Under the alternative ‘flattening the curve’ strategy there are perhaps 25,000 to 55,000 deaths, or 125,000 to 275,000 life years lost.

We need to protect our older people and people with chronic disease from coronavirus, but there is a cost.

But we need to factor in the chance of success of an eradication policy which, based on NSW’s and Victoria’s announcement, may be what these States are pursuing – but they have not outlined what their goal is here.

Let’s assume eradication only has a 25 per cent chance of success, and therefore a 75 per cent chance of failure, or defaulting back to ‘flattening the curve’.

That means the expected life years lost under eradication = [25 per cent × 25,000] + [75 per cent × 125,000 to 75 per cent × 275,000] = 100,000 to 212,500 ‘expected’ life years lost.

It is the difference (or what economists call the increment) between the scenarios of eradication and flattening the curve that really matters.

Combining worst- and best-case math, the expected gain for eradication over flattening the curve is 25,000 (125,000 minus 100,000) to 62,500 (275,000 minus 212,500).

Not as good as we might have hoped, but contingent on the above assumptions.

How much do we spend to try to reap this expected gain? Based on rules of thumb in the health sector (e.g. decisions on which medicines to approve and fund) – about $A100,000 per life year.

This implies that as a society, and considering all differences in costs between attempted eradication versus flattening the curve (e.g. in the health sector, across the economy – and factoring in that eradication may be better in some aspects through a more ‘normal’ economy in three months time), society might be prepared to spend up to $A2.5 to $A6.25 billion more to ‘give eradication a go’.

These are quick calculations. There are other considerations too, like allowing mathematically for morbidity and the capacity of the system.

Our calculations could and should be improved.

The Government has 48 hours to do so. We hope this helps.

This article was written by Professor Tony Blakely, of the University of Melbourne, and Professor Nick Wilson of the University of Otago. It was published by Pursuit.

Nick Wilson is a medical doctor who subsequently specialised as a public health physician and then moved into university-based research. He is currently a Professor at the University of Otago in New Zealand where his research encompasses infectious disease epidemiology and control.