Back of the net, Buntaram

The crowd of 5,000 Victory diehards who turned up at AAMI Park to watch the Victory-Bali United game was a far cry from the euphoric celebrations in Western Sydney when the Wanderers beat Al-Hilal way back in 2014. Little else encourages attendance more than winning.

Bali United and Melbourne Victory players tussle for the ball in the Asian Champions League.

The game, however, was played only a few metres away from the site of Indonesia’s greatest footballing achievement: a 0:0 draw against the mighty USSR during the 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

Football (or soccer as it’s known in Australia), as with sport in general, is a reflection of our cultural and ideological biases and prejudices. Playing sport is a means to establishing networks and alliances.

Who we look to play with indicates with whom we identify.

Our great sporting rivalries are often against those who we are most similar to, but also, who we seek to assert our minor differences from.

There is no natural rivalry between Victory and Bali Utd as the two clubs come from vastly different contexts. Appearances however can be deceptive –both clubs are successful in their own domestic leagues which are both on the path to increasing professionalisation and commercialisation.

Indonesia’s influence on Australian soccer

Bali United, founded in 1989 in East Kalimantan as ‘Putra Samarinda’, changed its name and moved to Bali in 2014 to improve its marketability.

But there are few signs that this marketability is working in Australia, with little engagement with Indonesia in the A-League. The Indonesian and Australian leagues are developing along different tracks; each largely ignoring the other.

Bali United was the first soccer club in Southeast Asia to list its shares on the stock market.

There is however some interest in Australian teams from Indonesian sponsors. The noodle company IndoMie appears as a sponsor on the shorts of Melbourne City players, and Brisbane Roar is owned by the Bakrie Group, a conglomerate with interests in mining, oil and gas, property development, infrastructure, plantations, media and, of course, sport.

The Bakrie Group, problematic as it is, clearly sees some kind of commercial relevance in being in the A-League. But Brisbane Roar fans have been disappointed with the Bakrie Group’s ownership of the proud – but currently middling – club.

The match between Melbourne Victory and Bali Utd had some local coverage in Melbourne, but nationally, it was limited. There was some reportage by AAP that appeared on Victory’s own website and on SBS’s The World Game. Indeed, this was about as low-key as possible for an international competition of ‘the world game’.

This indifference contrasts with the coverage of fan violence in Indonesia which seems to dominate Australian coverage of Indonesian football.

The ABC’s Foreign Correspondent story on the issue shows fans in a largely decontextualised setting in which fan violence is largely divorced from everyday social and political complexities.

Presented with the opportunity for a football story; sports journalists and mainstream media don’t seem interested. When presented with an opportunity to cover violence, a full program is dedicated to it.

Coverage of Indonesian fan violence seems to dominate the coverage of Indonesia football in Australia.

Indonesian fans were represented as “fundamentalist” and likely to “run amok”. This focus on “violent hooliganism’ was an “an easy pitch”, according to the journalist, David Lipson, who covered it.

But the roots of the country’s football violence is related to ongoing corruption in Indonesia’s football association PSSI, bureaucratic mismanagement, the financial instability of clubs, stadium design and security, as well as poor urban design and policing.

Strong supporter bases

While clubs in the A-League remain effectively indifferent to Asia, there are other examples which indicate more positive respect for Indonesia and Southeast Asia.

During the early 1980s, when the professional Galatama League was taking off in Indonesia, famous English club Arsenal lost 0:2 to the now defunct Niac Mitra, despite playing their best team. This is ancient history in the context of changes in sporting economies.

The English Premier League and Italy’s Serie A teams, however, have established strong supporter bases in Indonesia. These official fan groups further strengthen interest in the clubs as global brands.

They present fans with opportunities to win tickets to watch giants like Liverpool, Juventus and others, at their home grounds. The clubs themselves though have made recent visits to Southeast Asia.

The Japanese football player Keisuke Honda’s year-long stint at Melbourne Victory didn’t have a significant increase on crowd size or on-field performance. And he is arguably the best Asian player of his generation.

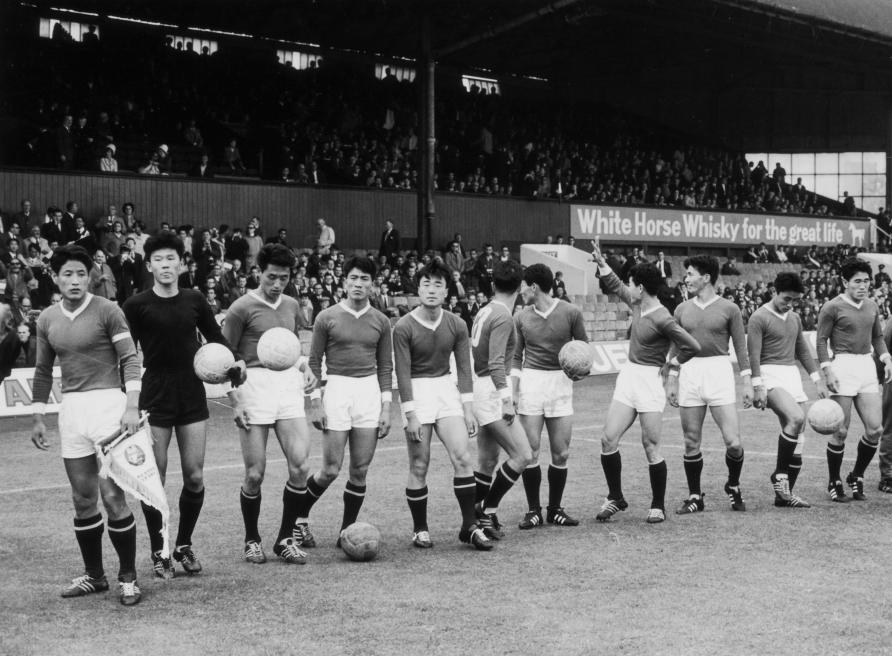

The North Korean team that beat the Australian national team over two legs to qualify for the 1966 World Cup.

Following in Europe’s footsteps

A-League clubs could do well to follow the example of those European clubs working throughout Asia.

But, perhaps, the argument is that the Australian clubs are too cash strapped and are yet to establish their own brand in Southeast Asia.

They would be following in the footsteps of the early incarnations of Australia’s national football team, which toured to the not-yet independent Indonesia in 1928 and 1931.

The late Australian soccer player and commentator, Johnny Warren, wrote of his ignorance and respect for the North Korean team that beat the Socceroos over two legs to qualify for the 1966 World Cup – “they were skilful, disciplined and … professional. […] They had given us a startling and revelatory eye-opener into the quality and depth of international football.”

The Socceroos lost 6:1 in front of a crowd of 60,000 in Phnom Penh.

Sportswriter Joe Gorman, in his book on Australian soccer, wrote that in 2014-15, “I began to think we were approaching an historic Asian moment.”

But the paucity of coverage and knowledge of any Asian leagues, the indifference to the Asian Champions Leagues and the rarity of Asian players in the A-League all indicate that Gorman’s sense was somewhat optimistic.

Australia perpetually stutters in its engagement with Indonesia – this is seen diplomatically, linguistically and culturally.

Playing sport can be a means to establishing networks and alliances.

The former head coach of the Australia national football team, Ange Postecoglou, was rightfully proud of his success guiding the Socceroos to becoming the champions of Asia. He is also suitably proud of his recent success in Japan’s J-League.

As Postecoglou writes in his book Changing the Game “if football in Australia wants the benefits of Asian membership, then it has to also endorse Asian football.”

“We can’t pick and choose, the relationship can’t be one of convenience. It must be symbiotic.”

This article was published by Pursuit.

Dr Andy Fuller researches Indonesian literature, the politics of sport and urbanisation and the negotiating of Indigenous identity in Australian sport at the University of Melbourne.