How not to make a bed – synthetic drugs in Australia

Sophisticated synthetic drugs are flooding the Australian market, and for every drug banned there are five others lurking in the wings. Emergency consultant and illicit drug expert Dr. David Caldicott says a temporary ban on these products is just a starting point to buy us some time.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Santayana, G. (1906): “Reason in Common Sense” in The Life of Reason Vol.1.

The illicit drugs market has undergone a revolutionary change in the last decade. Home-grown marijuana, home-made methamphetamine and imported heroin have all been eclipsed in profile by the new kids on the block, the novel psychotropic substances (NPSs).

In retrospect, we should have seen it coming. Like Cassandra, some of us did, but were unable persuade anyone that a storm was on its way.

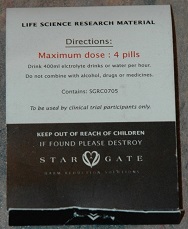

Photos: ‘Ease’, the ancestor of current legal highs in Australia (© Dr David Caldicott, ACTINOS Collaboration)

Back in 2005, at a conference in Sydney, pills were being handed out for free, with the reassurance that they were completely legal (photo). We took them back to Adelaide for analysis and demonstrated that they were pharmaceutical grade methylone, a product that none of us had even heard of, and which was the first legal high that we had collectively ever seen. In 2007, we identified, for the first time in Australia, mephedrone in capsules, now widely regarded as the ‘Queen of the New Stoned Age’. These were the first spots of rain in what was to become a monsoon.

As medical professionals, what could we expect to emerge from such an evolutionary crucible, where the principal selection pressure was merely enforced limitation of drug supply? If the illicit market were a virulent infectious disease, one which was largely being treated for 50 years with only a single antibiotic – let’s call it ‘Interdict-icillin’ – we would have been stunned had resistance not developed. The only surprise about the emergence of more nimble markets is that anyone is surprised.

Let us be very clear here – this is a mess of our own creation. Evolutionary pressures on the more traditional and cumbersome markets, from both the supply and demand sides of the equation, have rendered them uncompetitive. On the demand side, an insatiable search for novel sensations, coupled with the unique selling points of a general inability of standard screening tests (or sniffer dogs) to identify NPSs, and their ambiguous legal status, has resulted in a huge surge of interest from the consumer.

The perfect storm is finally achieved by an explosion of information, immediately available on the World Wide Web, describing products as they emerge. The spread of ideas, including drug trends, has become more virulent, and using the virtually impregnable Silk Road and its successors as a source of acquisition has meant that the street corner dealer has been made redundant, replaced by the more cheerful and significantly less armed-and-dangerous postie.

On the supply side, why wouldn’t suppliers elect to provide a product of ambiguous legality and unquestionable purity, with minimal risk of seizure or confiscation? The products currently on the market are far too sophisticated to be the creations of meth-addled tweakers working out of car-boots and cheap hotel rooms. They are sidelines of inconspicuous multinational industrial chemical plants, the owners of which have realised that it is as profitable to produce a 100kg batch of novel product on demand as it is to produce 100 tonnes of their rather duller industrial solvent. The traditional clandestine routes from South West China remain the same – all is already in place for a risk-averse supply chain. The new market is intelligent, reactive and dynamic, and for every drug banned, there are five lurking in the wings, waiting to take its place.

Like the emergence of a new strain of influenza, we are faced with something more than the innocuous yearly antigenic ‘drifts’ in drug consumption – this represents a tectonic antigenic ‘shift’. It presents an opportunity to re-evaluate how we deal with the issue of recreational drugs in modern Australian society, an opportunity that may not present itself again for a generation. A temporary ban on these products is a good starting point, to at least buy some time to decide what we want as a country.

There is an excellent tradition of harm-minimisation in Australia, but every generation of drugs requires its own specific tactics. The NPS market is attempting to regulate itself, and this should be welcomed and guided rather than dismissed. New Zealand legislators have been prepared to bravely embark on a trial of legalized social tonics, marking a fresh approach to the issue which is unlikely to be worse than current global policy, and which may yet yield very positive health benefits.

In addition, we need to get a handle on the population harms caused by these products, and not just the dramatic and tragic examples selected by the media for our consumption. How much harm do they cause compared to our traditional illicits, especially compared to our true ‘legal highs’, alcohol and tobacco or to diverted pharmaceuticals? To truly reduce harm, we need to be able to identify and accurately measure it, rather than rely on sensationalist anecdote and politically charged rhetoric. One measure of medical harm which might seem obvious to the lay reader is to record the acute medical harm associated with emergency department attendance; however, no robust system of recording these harms is in place in Australia.

There is a real risk of disconnection between consumer and legislator if credible control options are not used. Simply banning products as they turn up on the market merely turns up the temperature in the crucible, encouraging the emergence of products never before seen in human poisoning. This is a dangerous place to be, ensuring that emergency medical professionals charged with treating overdoses may never be able to fully get a handle on what they will be faced with.

Merely banning the packaging of legal highs, as most recently proposed by several state governments, is a laughably inefficient use of resources, akin to the use of sniffer dogs in Australia, or the hilarious-if-it-wasn’t-serious suggestion by the previous federal government of banning any plants that contained dimethyltryptamine. The latter would have resulted in the outlawing of several native state and federal floral emblems, including wattle and the Sturt desert pea, plant species more likely to spontaneously become carnivorous than to become significant players in a new drugs panic.

Worse than merely being a failure, “The War on Drugs” has been an unmitigated disaster, a slow motion train-crash that has cost trillions of dollars and adversely affected the lives of billions of individuals – with no real net gain to public health. In the recent federal election, one of the most uninspiring in living memory, neither of the major political parties displayed the moxie to take a position on drugs policy. It has been a greater crime in Australia to appear to be ‘soft on drugs’ than to propose any meaningful policy other than the now out-dated approach of prohibition. With the re-election of a party traditionally committed to an ideological agenda on illicit drug use as opposed to a medical one, AOD workers around the country are nervously hoarding their grant money in mattresses, while the suppliers of sniffer dogs lick their lips in anticipation.

The author cited in the beginning provides us with another quotation to finish with: “Fanaticism consists in redoubling your efforts when you have forgotten your aim”. As a society, as a species even, on the issue of recreational drugs, we need to decide what our aim is, and who it should fall to decide what our aim should be.

Should it be left in the hands of those whose job depends on the result of a popularity contest, whose position can be swayed by the influence of lobby groups, and for whom a ‘moral panic’ is not necessarily a bad thing? Or does the public have the right to expect that our policies be based on independent, peer-reviewed evidence, conducted by individuals who have worked in the field for a lifetime?

Is it more important to stop individuals from consuming drugs, no matter what the consequences, even if those consequences are that more young people contract blood-borne viruses, or diseases yet to be defined, or even if it means more of them have to be incarcerated or actually die as a lesson to their peers? This is the essence of prohibition. Or should we do whatever we can to stop young people getting hurt, even if it means providing them with messages about how to stay safer during their overwhelmingly self-limiting drug-using career?

It is the responsibility of physicians to inform these policy choices and to insist that the tyranny of dogma is not given the opportunity to suppress evidence. This is a time for evidence-based policies, and not policy-based evidence. This is our bed, and it’s our choice as a society not only how we and our children lie in it now, but also how to make it for the next generation of young Australians.

The opinions in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those held by Calvary Hospital or ACT Health.

Dr. David Caldicott is an Emergency Consultant at the Emergency Department of the Calvary Hospital in Canberra and a Clinical Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Medicine at the Australian National University. He is a spokesperson for the Australian Science Media Centre on issues of illicit drug use and the medical response to terrorism and disasters. Dr. Caldicott designed and piloted the Welsh Emergency Department Investigation of Novel Substances (WEDINOS) project in the UK, a unique program using regional emergency departments as sentinel monitoring hubs for the emergence and spread of novel illicit products, and is currently replicating this work in Australia with the ACT Investigation of Novel Substances (ACTINOS) Group.