Learning the lessons from bushfires – again and again and again

The Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria, which claimed 173 lives and destroyed 2,133 homes, were the worst bushfire disaster in Australian history. After the devastation, a Royal Commission was called to investigate how the fires occurred and caused so much destruction.

The Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission ran for 18 months, called 434 witnesses, produced 67 recommendations and cost an estimated A$90 million. But, this Royal Commission is only one of over 50 formal inquiries into bushfire management in south-eastern Australia since 1939.

So, we have difficult questions to ask ourselves:

Why do we need so many public inquiries? What effects do they have on bushfire management and bushfire risk? What role do universities, training and research organisations have in improving bushfire management?

Fixing a flawed system

There are two broad reasons to hold these kinds of formal inquires.

The first is to fix a flawed system – making it more effective, efficient, sustainable, responsive and/or accountable. The second reason is to provide a new direction in fire management vision, culture and/or philosophy.

But, more often than not the public and media want someone to blame, and to take legal and financial responsibility for personal, business and public losses. This multiplicity of purpose often leads to these inquiries not achieving their intended goals and objectives.

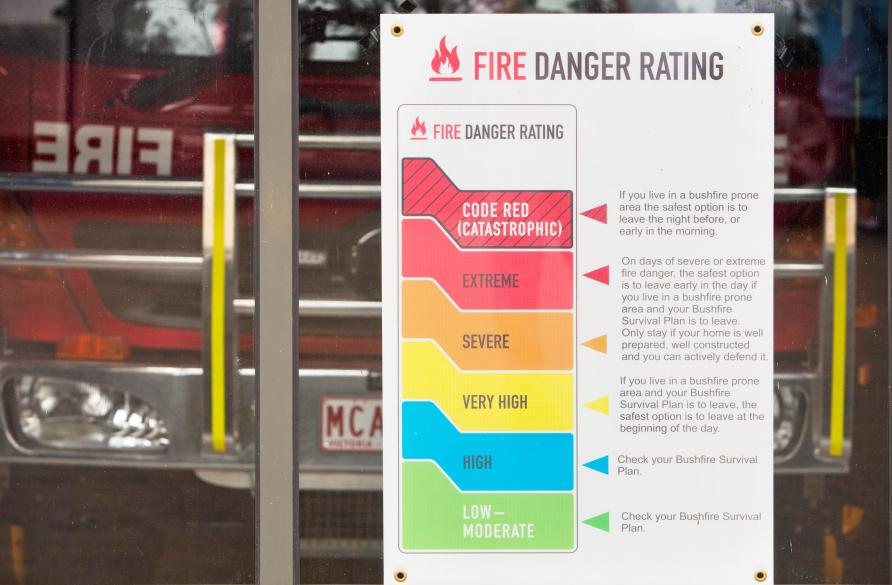

The Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission acknowledged that the responsibility for preparing and responding to bushfires is a “shared responsibility” between people as individuals, families, and members of the community and the government, through various government agencies like the Country Fire Authority (CFA) and Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP).

But, the implication of the recommendations was that the “government” needed to be more accountable and take control in bushfire emergencies through efforts like appointing an Emergency Services Commissioner. This then largely down-plays the role and responsibility of the public.

The elected government has also reinforced this mis-interpretation of the Royal Commission’s recommendations because it wants to be seen as strong, reliable and empathetic and, as a result, deserves to be in power and to govern.

The Government and its agencies has also been timid in applying land-use planning regulations in bushfire-prone areas. While the CFA, with its experienced and specialist bushfire planning staff, has been removed from its role as a planning authority with the power to accept or reject planning applications for buildings and developments in bushfire-prone areas.

The CFA is asked for their opinion, but it is local councils, and their planning staff, that ultimately decide whether or not a planned development should proceed.

Balancing the risks

Government agencies, such as DELWP, Parks Victoria, and CFA, have been charged with undertaking fuel hazard reduction programs on public land, but, there is little effort to reduce fuel hazards on private land.

Fuel hazards on private land in some areas may represent up to 70 per cent of the bushfire risk to the community, but little or no responsibility is given to the private land owners on whose land the fuel hazard exists.

Any hazard reduction programs can also be seriously hampered by public and media concern about smoke impacts and the occasional escaped burn.

In fact, some of the implications of the inquiry into the Lancefield escaped planned burn in November 2015 have gone well beyond improving planned burning and implementation, to significantly reducing the extent of planned burning – and this means an increased level of bushfire risk.

But little effort has been made by government agencies to balance the level of landscape bushfire risk, with the risks of local losses from escaped planned burns. Escaped burns occur fewer than two out of every hundred operations, and escapes with the impact of the Lancefield fire are more like one in a thousand.

What was saved

Today, with government agencies primarily responsible to the Government of the day rather than to the public, there’s a high expectation of having to be fully accountable for their actions (and rarely to any inactions) to a board of inquiry.

To this end, the level of documentation and strict compliance to process, outweighs the need to be effective and efficient.

A significant amount of effort and attention is given to matters that might attract criticism, but much less attention and effort is given to what can be achieved.

For example, on Black Saturday, 173 people died, but about 15,000 people were in the fire-affected area. Little attention was given to the reasons behind so many people’s survival.

Similarly, about 2,000 houses were destroyed, but about 9,000 houses were in the fire affected area. We do not know as much about the 7,000 houses that survived as the 2,000 houses that were burnt.

Our bushfire future

This attention on reducing negative criticism misses the opportunity to recognise and build on the successes and to evaluate the bushfire emergency efforts on the day in terms of what was saved against what was lost.

Since Black Saturday, we have not been able to change our thinking and management to negotiating the real and acceptable level of bushfire risk we want and can afford to have.

The propensity for inquiries has had the perverse effect of making bushfire management less effective and efficient than it should be.

Politicians and public agency leaders have not been prepared to have a fair-dinkum engagement with the community so we can truly “share the responsibility” and not just shed the blame.

Education, research and training organisations have the ability to train better decision-makers for our bushfire future; but that is pointless if the demand is for bureaucrats and public relations consultants.

This article was published by Pursuit.