The ANZAC Book

On 26 March 2010, I had the honour of giving a speech at the launch of The ANZAC Book at the Australian War Memorial. It’s a great book, and as we all get back to work following the ANZAC day long weekend, I’d like to share this transcript of what I had to say on the day.

I guess many of you here today would know of the English author Antony Beevor, who’s famous for his account of the battle of Stalingrad.

I had a yarn to him in Melbourne last year when he was here to promote his new book, which is on D-Day (D-Day: The Battle for Normandy).

I made the remark – and I thought it sensible at the time – that he was fortunate that so many survivors of D-Day were still alive and able to tell him things.

He surprised me by saying that this didn’t count for much.

Why? I asked.

Because, he said, ‘I’m not so much interested in what they think now. I’m interested in what they thought then.’

It’s a nice point. And it’s one of the charms of this book we’re here to launch today. The book tells us something of what men thought then – in 1915, on Gallipoli and cut off from the world.

The Anzac Book is a true Australian artefact. It’s a child of adversity. And, as the Director says in his preface, it’s also a time capsule. There’s no war book that I know of that’s quite like it.

It was conceived and written and sketched on scraps of paper by men who lived in holes in the ground and who were under fire twenty-four hours a day.

All of the content came out of the tawny ridges above Anzac Cove, a foreign place – much more foreign then than it is now – and yet much of what is in the book is hopelessly Australian in character. The ghosts of Henry Lawsonand C. J. Dennis rise out of the pages.

We should say at once that this book is not the story of the Gallipoli campaign. That would have been too terrible to tell back then — and in truth much of it couldn’t have been told for reasons of security.

This book is mostly about Australian humour and whimsy, about the Australian custom of making a joke out of adversity – be it a drought or a war – and about the old Australian habit of not taking oneself too seriously, and of not taking those in authority seriously at all.

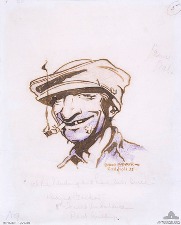

I think the sketch that best captures the spirit of the book is this one [p. 35] by David Barker.

I think the sketch that best captures the spirit of the book is this one [p. 35] by David Barker.

Look at the mischief in the eyes. He’s been to what C. J. Dennis called ‘the flamin’ war’ — but it hasn’t got him down. He’s lost most of his teeth but he can still smile, probably because he’s just won at two-up and bandicooted someone’s cigarettes. He’s had dysentery and strangers have been shooting at him and the brass has been picking on him – but who cares? You just know this bloke is a practical joker and a scrounger and a larrikin and that he’ll always come up smiling.

You only see faces like this in country towns these days. That’s another thing about The Anzac Book. It’s about the old Australia which, for better or worse, is now mostly gone.

When Charles Bean, the editor, called for contributions, the Australians had been on the Peninsula for more than seven months. They were still pretty much trapped in the shallow beachhead that had been defined in the days after the landing. The August offensive, the true climax of the Gallipoli campaign, had failed with frightful losses. The men by now knew that their generals were out of ideas. Ten thousand Anzacs were dead and the survivors were worn out.

Yet out of this world came this book. Few books of such good humour have been produced in such wretched conditions. Bean received some 150 contributions, and, as with most, anthologies the material is uneven.

General Birdwood strikes a false note in his introduction by invoking the Harrow school song, which, when you think about it, wouldn’t be that well known in the boot factories of Collingwood or the shearing sheds along the Darling.

But there is lots of gentle humour. The bit I like best is in the classified ads at the back. It comes under the heading ‘Warning’ and reads:

Men are advised to keep their eyes open for an individual wearing pink pyjamas, green glasses, straw hat and khaki mackintosh. It is thought that this is a spy in disguise.

And in this edition, thanks to Ashley Ekins, the Head of Military History here, we see for the first time some of the contributions that Bean rejected. Across the years some academics have claimed that Bean used The Anzac Book to present an idealised view of Anzac legend. We need to touch on this briefly.

As I said earlier, this isn’t the story of the Gallipoli campaign and Bean would never have claimed that it was. And, yes, it’s true that as early as 1915 Bean had become the keeper of the flame, and, yes, Bean occasionally exercised a sanitising hand.

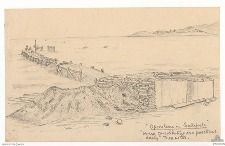

There’s one pencil drawing I would have loved to have seen in the book. [p.XXV] It shows a derelict pier stretching away from a derelict dugout and carries the caption: ‘We are consolidating our positions daily.’ This is a send-up of the absurdly optimistic reports General Sir Ian Hamilton sent back for publication throughout the campaign.

There’s one pencil drawing I would have loved to have seen in the book. [p.XXV] It shows a derelict pier stretching away from a derelict dugout and carries the caption: ‘We are consolidating our positions daily.’ This is a send-up of the absurdly optimistic reports General Sir Ian Hamilton sent back for publication throughout the campaign.

But, equally, I can understand why Bean felt he couldn’t use the drawing at that time. And there’s another small point to make here.

Editors are meant to edit, and editing isn’t objective. It’s about one person’s perceptions of taste and tone and of what constitutes good prose. So we shouldn’t be too literal. We shouldn’t assume that the omission of a piece or a sketch automatically amounts to censorship rather than the exercise of that oxymoron people in my vocation call editorial judgement.

Generations of Australians owe Bean so much, and I think we should see this book for what it was meant to be – a diversion, something to amuse the men as they prepared to spend winter in a hellhole.

It was certainly the most successful book Bean was associated with, selling 100,000 copies in 1916 alone.

Now, ninety-four years later, we have the book again, this time as an Australian curiosity, and I must congratulate Kathy Bail and the University of New South Wales Press for such a splendid production, right down to the deckle edges.

I should also thank the many people at the War Memorial who brought the material together and edited it, and particularly Ashley Ekins, whose introduction offers the most balanced perspective I’ve read on the book.

Right … after all that the book is launched and congratulations to all, but I’d just like to say one last thing.

Last time I launched a book here I ended by saying: Please buy a book because we need the money.

Well, that was a while ago and since then, to quote Damon Runyon, we’ve begun to feel the economic depression keenly. So why not buy one and one for a friend? It’s not often you can buy deckle edges for less than fifty dollars.

Les Carlyon is an Australian writer. He has been editor of Melbourne's journal of record, The Age, as well as editor-in-chief of The Herald and Weekly Times Ltd, and has twice won the Walkley Award for journalism. In 1993 he won the Graham Perkin Australian journalist of the year award. His book Gallipoli was published in 2001, and met with critical and commercial success.