White supremacy and the Australian politics of race

When an Australian white supremacist killed 50 people, and injured 50 others, in two New Zealand mosques last week, the politics of race and religious hatred merged into one. Questions were raised of how Australia, or New Zealand for that matter, provided ground for this depth of hate to develop.

In neither country is racially inspired violence of such magnitude unprecedented. Massacre was colonial strategy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Indigenous peoples well remember.

Nevertheless: ‘This is not us’ summarises the New Zealand Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern’s powerful and unifying response to Friday’s massacre.

In Australia it ‘is not us’ in the sense that nobody of consequence has supported the targeted killing of this multi-ethnic, largely immigrant group, at peaceful worship.

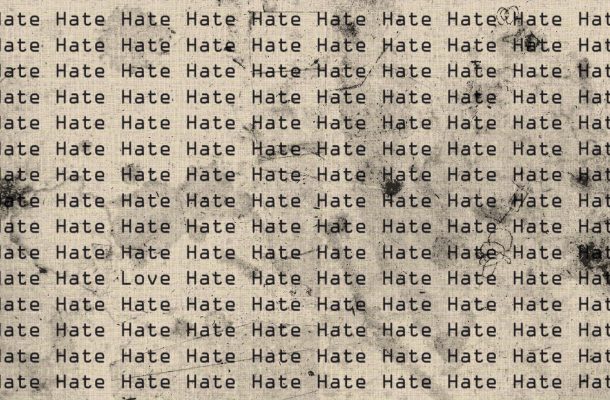

But it is ‘us’ in the sense that white supremacism, the ideology driving the Christchurch killer, is prominent and influential in our politics.

Fraser Anning and Pauline Hanson express it blatantly and explicitly. In his first speech to the Senate in 2018 Anning used Nazi rhetoric to propose a ‘final solution’ to non-white immigration. While leaders of the Government and Opposition denounced the speech, the independent Member of Parliament, Bob Katter, called it ‘magnificent’.

For Hanson, there was an ‘absolutely disgusting’ prominence given to Indigenous dance in the opening ceremony of the 2018 Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast. In 2017, she explained her view of Islam: ‘Let me put it in this analogy – we have a disease, we vaccinate ourselves against it’.

Anning cannot be dismissed as a fringe voice, whom the voters will reject at the election in May.

He did attract just 19 personal votes at the 2016 election. But in an electoral system where people choose, in the main, to vote for parties not individuals, that is meaningless.

250,000 people in Queensland voted for Pauline Hanson’s One Nation. Although later falling out with Hanson, Anning was elected from her ticket. But these are not the only people who think ‘it’s okay to be white’.

The corollary is not that it’s equally ‘okay to be black’. It’s ‘ok to be white’ is a widely used white supremacist slogan supported, although apparently by ‘mistake’ by Government senators, when Hanson put the proposition to the Senate in 2018.

McGrath’s Senate colleague Amanda Stoker was also in the photograph.

When the Morrison Government withdrew permission for the political activist Milo Yiannopoulus to visit Australia following his comments on the Christchurch massacre, Stoker objected, saying that she was ‘troubled’ by the decision and that Yiannopoulus was ‘entitled to his opinion just like everyone else in the world’.

The solution for those who don’t like his ideas, the Liberal National Party Senator said, is for others to promote ‘other, better ideas’.

One better idea is respect. Another, which Jacinda Ardern put to the US president Donald Trump, when he asked what his country could do to support New Zealand after the massacre was ‘sympathy and love for all Muslim communities’.

McGrath and Stoker are not fringe players. They are members of the Australian Government. They represent a party that attracted more than 960,000 Senate votes in Queensland.

The Labor leader Michael Daley’s campaign for the premiership of New South Wales was also marked by the politics of race.

Though he denies his comments to a party fundraiser about ‘Asians with PhDs’ ‘taking our kids’ jobs was an intended racial slur, his party has been forced in to damage control among voters in marginal seats, where the Asian vote is sufficient to make a difference.

Last-minute advertising in Sydney’s Chinese newspapers failed to undo the damage done. Race was used to put people on the margins; just as Section 25 of the Commonwealth Constitution envisages when it provides for the exclusion of members of some races from the right to vote:

Daley says that he didn’t intend to cause offence; that his words were poorly chosen. But it is clear that the ‘our kids’ to which he referred are just some not all of ‘ours’.

In a multicultural society with 49% of its population either born overseas, or the child of at least one overseas one parent, excluding, marginalising or vilifying so many is dangerous.

Indigenous, immigration and refugee policies are developed and debated as a politics of race.

The Senate will censure Anning, though the motion will not have Hanson’s support, just as it took exception to the One Nation leader’s wearing of the burqa in the Senate to vilify Muslim women in 2017.

The Senate cannot and should not expel Anning as 1.3 million petitioners have asked. That is the people’s job at the election if that is the democratic wish.

Racism’s pervasive influence is a deeper problem for which decisive and unequivocal national leadership is required. The Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition have provided that in statements over the last week.

However, it is not clear that Australia’s political system will support enduring leadership of that kind.

Dominic O’Sullivan is Professor of Political Science at Charles Sturt University and Adjunct Professor in the Centre for Maori Health Research at the University of Auckland University of Technology. His recent publications include ‘We Are All Here to Stay’: citizenship, sovereignty and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Sharing the Sovereign: Recognition, Treaties and the State.