Will COVID-19 change attitudes to unemployment?

While advice abounds about how to use your newly found ‘spare time’ productively, to learn a new skill or catch up on your Netflix viewing list, the reality of being in the dole queue is hard – practically and emotionally – and many will be finding their first experience of Centrelink more demoralising than supportive.

So if you find yourself in this situation, what can you do?

Thousands more Australians now have first-hand experience of the unemployment system.

Stigma is not personal

The first piece of advice is not to take it personally – what you are feeling isn’t about who you are, it is the product of many years of messages on what we have all been told to think about people who are unemployed and who turn to Centrelink for help.

Despite the government committing $17.6 billion in stimulus packages and over $130 billion to unemployment benefits and wage subsidies, and aside from the practicalities, the reason accessing these supports remains hard is one of cultural and political stigma surrounding unemployment and its associated systems of relief.

What this crisis has done is shine a light on the stories we have been told about the unemployed, including who they are and how to ‘manage them’.

Since the 1980s, successive governments have delivered consistent messages about the unemployed based not on social factors that stopped a person finding work such as the declining manufacturing sector, age-based discrimination or the rise of casual and short term contracts, but on the deficiencies of individuals.

A social contract

These messages were based on ideas such as the need to require ‘active participation’, that support is a contract of ‘mutual obligation’ between individual and the state, and that without strict requirements for these concepts, unrestricted support for individuals will be the foundation of welfare dependency.

The way these messages were packaged for the wider community, however, was in the language of ‘welfare cheats’, ‘dole bludgers’, ‘lifters not leaners’. For the last thirty years the community has been consistently fed the stigmatising idea that unemployment is a lack of individual moral fibre.

Accessing unemployment support remains hard because of cultural and political stigma.

Economically successful governments have taken no responsibility for unemployment but instead laid this at the feet of defective Australians who must therefore be lazy and angling for a free ride.

The reality of the health and economic crisis that we now find ourselves in, is that it highlights the degree to which this messaging has become culturally accepted and normalised.

Thousands more Australians are unemployed

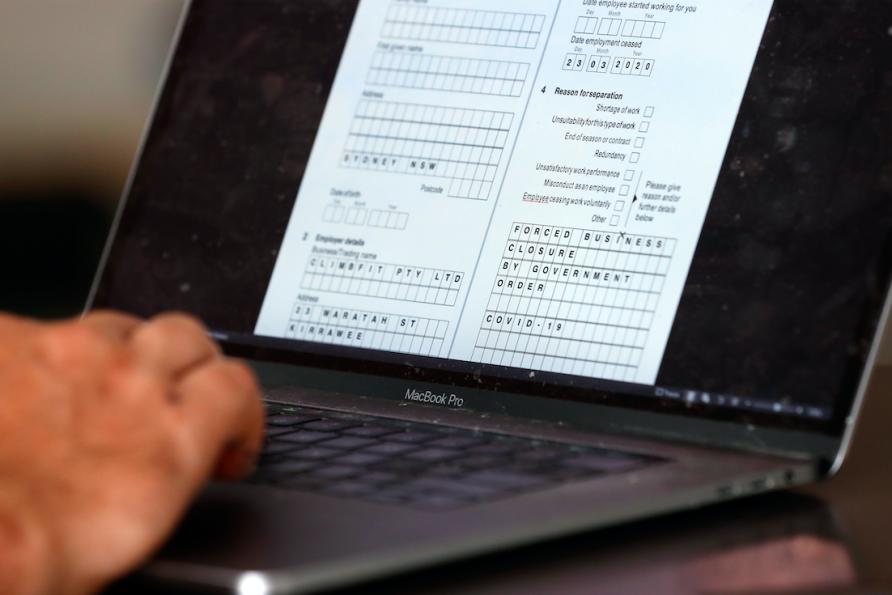

On March 23 alone, over ninety thousand people found themselves in the ‘dole queue’ either in person, online or on the phone. In this moment they shifted from ‘lifters’ to ‘leaners’ in the government’s longstanding message.

Thousands of quiet Australians now have first-hand experience of how these complex systems designed to punish ‘bludgers’ into self-sufficiency, can also make people legitimately applying for help, feel ashamed and unsupported.

In need of immediate financial assistance, people have been forced to make applications, ascertain the documentation required and going forward will need to justify why unemployment continues.

Research shows however that these hurdles to support can leave people questioning if they are ‘deserving’ of this or any other assistance, damaging their sense of self-worth and their emotional wellbeing.

The practical challenges of applying for benefits through Centrelink are also part of this government messaging, so again, when you are struggling to understand the online system or get through on the phone line, it’s not you, it was built this way.

Application processes for financial support can take far more time than those that cut you off.

A complex system

Over time, the focus on individuals taking responsibility for their own circumstances has led to increased complexity a range of areas, with vulnerable individuals struggling to navigate and make the most of systems designed to support them.

Centrelink processes online and by phone are complex and restrictive, staff numbers have been cut dramatically with a reduction of 1,280 staff in the 2018-9 Budget, and provisions are at just meagre levels of support ($556.70 per fortnight for an individual with no dependents).

Not only do people in this system not receive enough funds to subsist upon, they also owe a level of compliance in the form of recording keeping and activity to demonstrate their worthiness even of that.

In the announcement of the current stimulus package Prime Minister Scott Morrison has drawn a clear delineation between those who were unemployed before the COVID-19 crisis, where increases to Newstart would be mere “unfunded empathy” and those who are unemployed as a result of it, where Jobseeker shows twice the support is required to subsist.

The measures the current government has taken to support the economy, business and workers are extraordinary (the $130 billion JobKeeper package to assist businesses keep workers off Centrelink queues is the largest single spend by an Australian government ever recorded).

Many systems have been simplified and compliance relaxed. However, despite this and when forced to engage with the bureaucracy of Centrelink, it is difficult for people to shake the very normalised image that being in the dole queue equates to personal failure.

Firsthand experience of the unemployment system has the capacity to generate real empathy for people in similar situations.

Will attitudes to unemployment change?

The second piece of advice is not to be too dazzled by the shiny new stimulus package. The ‘snap back’ to systems and messaging of old foreshadowed by the Prime Minister, says this is a temporary change of attitude not a fundamental change of ideological heart.

As with Centrelink – where application processes can take far more time than those that cut you off – the transition from the ‘underserving’ unemployed to the ‘pandemic (and therefore deserving) unemployed’ was slow, but eventually in the financial favour of many quiet Australians.

The ‘snap back’ however is likely to be far more swift, with generous payments ending and little systemic memory of an individual in need. For those seeking assistance when the pandemic is deemed to have ended, the indication from the government is that the generosity of funds, spirit or ideology is unlikely to last.

So the final piece of advice is to think carefully about the messages you have been sold in the past. How do they resonate with what you are experiencing now? Firsthand experience of the system has the capacity to generate real empathy for people in similar situations.

It can help us see beyond stereotypes which are the foundation of stigma, and see clearly the social, political and ideological barriers that must be battled in the fight for employment.

For many quiet Australians jobs will return, the dole queue will become a distant memory, but treating those looking for work with the respect they deserve need not be.

The question is often posed, how will we change as a country after this? Holding on honestly to our collective memories of the Centrelink experience will be the first step.

Retaining our empathy and compassion for the people who will inevitably still need government assistance, and keeping our gaze set on the barriers in their way, rather than their fictionalised individual deficiencies, will create a significant change for the better.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Jennifer Davidson is an Associate Lecturer in the School of Social Work at the University of Melbourne. Her research interests include workplace practises and social work in a time of change.