How will the arts recover from COVID-19?

Supporting artists during COVID-19

The first has arisen through on-going concerns about accessing financial support. The Federal Government has resisted calls for a nation-wide industry stimulus package.

The closure sign on the door of multi-arts centre Carriageworks in Sydney.

An array of initiatives at local, state and sector levels (like the ABC’s $5m development fund) are welcome, but piecemeal, with widely varying eligibility requirements and application procedures.

The sense of crisis in the performing arts was compounded in early April when the Australia Council for the Arts announced the results of its coveted four-year funding round.

As theatre scholar Caroline Wake reports, with a reduced overall budget and a greater proportion going to the major performing arts groups, the number of small-to-medium companies receiving four-year funding has dropped by 34 per cent from 144 in the 2015 round, to just 95 today.

There is a wide perception within the sector, articulated most forthrightly in a recent article by theatre critic and author Alison Croggon, that the fallout from COVID-19 has intensified a longer-term pattern of decline in support for the arts in Australia.

Claims by Federal Arts Minister Paul Fletcher that the JobSeeker and JobKeeper schemes between them represent the “single biggest government investment to support our arts and creative sector that we have ever seen” have cut little ice.

Many arts workers are reliant on serial short-term contracts, meaning they have struggled to qualify for the JobKeeper package, which is primarily targeted at employees who have been working for the same company for at least a year.

The cultural sector adapts to lockdown

The second theme to have emerged during the pandemic concerns cultural responses to the lockdown itself. For many – especially in the hard-hit performing arts – skilled, resource-intensive and invariably highly collaborative work has simply stopped.

Other individuals and organisations have set about adapting existing materials as best they can to the newfound restrictions, luring users with all manner of digitised archives, virtual tours and streaming performances.

Still others have explored the middle ground by working with both the limitations and opportunities of online interfaces.

These have ranged from playful appropriations of Zoom’s instantly recognisable ‘gallery view’, to live-streamed festivals finding new global audiences for what would otherwise be local gatherings, to time-sensitive screenings and watch parties, aimed at recreating some semblance of a shared experience.

These developments have arrived on our computer screens so thick and fast, it is easy to overstate their novelty. However, if the pandemic has crystallised longer-term trends in arts funding, the same can be said of the move to online content delivery. It reflects changes with a much longer tail, in this case, concerning the impact of technology on artist-audience relationships.

Post-pandemic changes to art and audiences

Accelerated and intensified by the lockdown, key developments stand to shape the post-pandemic future of the arts industry in three ways.

Marking Time: Indigenous Art from the NGV Collection at NGV Australia available to view via Virtual Tour on the NGV Channel.

First, the phased easing of restrictions means that arts organisations will have to rethink what they understand a public event or exhibition to be.

Limiting tickets, managing queues, maintaining social distance and increasing levels of sanitisation are only the most rudimentary of a wholesale renegotiation of the relationship between venues and their missions. The idea of being ‘open to the public’ and maximising use will need to be revised.

The same will apply to arts workplaces. There, social distancing stands to impact not only how people work together, but the kinds of work that gets made, be it a dance without contact or, as reported by the ABC, in the case of shooting the popular television soap Neighbours, camera trickery “to make physically-distanced actors look more intimate.”

Second, the digital genie is well and truly out of the bottle. This has left Australia’s theatre sector looking particularly flat-footed.

By comparison with the wealth of streaming material on offer from Europe and Asia, relatively little Australian content has been available. This is the result of a combination of restrictive contracts, limited resources, and a long-standing – and arguably misplaced – emphasis on the ‘purity’ of the live experience.

One cannot imagine this situation will continue. During lockdown, those organisations that can afford it have significantly enhanced their digital assets, like for example educational and ‘behind the scenes’ materials. We can expect to see them put to extensive future use in audience development, alongside an expanded digital sensibility.

Processes of recording and mediation will increasingly be integrated into production for purposes of streaming-standard documentation. This sensibility is also likely to inform the creative process itself.

While multi-media events are nothing new, the development of transmedia narratives and hybridised, AR (Augmented Reality) experiences will be on the rise.

The third consequence of the lockdown will be changes to how artists and institutions work. Many artists whose careers survive the pandemic will emerge with an altered sense of what they do, and of their place in society.

A generation of artists has been compelled to see their labour, tax liability and employment status from the state’s point of view. Institutions have had to confront existential questions about who among their employees count as ‘essential’, and in what way.

Meanwhile, the search for alternative income streams has seen many individuals reframe their skills and talents as services for hire.

More broadly, we can expect to see a reconfiguration of the relationships between the various stakeholders in the cultural sector, though this will vary from place to place.

Some state governments have offered more support than others, while the ‘targeted’ sum of $27m that has been forthcoming from the Federal government has been directed at regional and Indigenous arts in a way that may signal a larger shift in priorities.

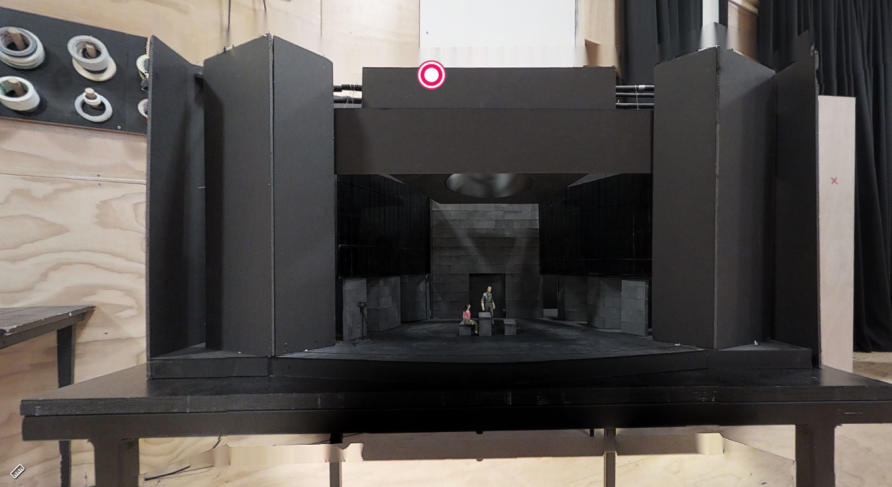

Still from the Melbourne Theatre Company’s virtual tour.

Relationships with the cultural sector

New support networks and institutional partnerships – like universities engaging artists in student mentoring programs – have been forged that will endure long after lockdown.

On the other hand, antipathy towards the Coalition government has been a constant of much arts commentary during the pandemic, and some existing tensions internal to the sector, like those between the major performing arts organisations and the small-to-medium and independent companies, may be exacerbated.

Calls are now growing for a sector-specific recovery package that might mitigate some of these challenges. Whatever the changes, however, one thing is certain. It remains the job of those working in the cultural sector to give voice to who we are, and form to ways of living together.

These are unique skills that will be all the more necessary as we look ahead to the creative challenges of recovering and rebuilding our society in the coming months and years.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Paul Rae is an Associate Professor In Theatre Studies at the University of Melbourne. He is the Senior Editor of Theatre Research International, and is currently completing a book entitled Real Theatre: Essays in Experience.