Friends, family, lovers – these are three mainstays in our intimate lives. We typically expect familial relationships to be solid, essentially for life. In our romantic lives, we search for the “one” to be with for life.

Friendships seem less important, at least in comparison. It is easy to think about friends as people who come and go with the seasons of life. This could be a massive miscalculation. There is a case to be made that friendship is not the third wheel to these other, more significant relationships.

Losing friends can be extremely painful. I was working as an ordained minister in the Anglican Church when I gave up my faith and ran off with a fellow church worker (who is still the love of my life). This had profound consequences, as you can well imagine. One of the most painful was that, almost overnight, I lost almost all of my friends.

I remember having lunch with one of them in the months after my sudden fall from grace. We had been best friends since high school. We had moved out of home together, shared a room together, played guitar together. We had been inseparable.

I tried to explain to him what I was thinking, why I could not believe what I used to believe. He looked me in the eyes and said, by way of conclusion, that the problem was not Christianity. “The problem is you.”

He refused to come to my wedding. That was 17 years ago and I don’t think we have spoken since.

Philosophers – both ancient and modern – have a lot to say about friendship. Aristotle theorised about friendship and has influenced our thinking about it ever since. In contemporary times, philosophers such as A.C. Grayling have written entire books about it.

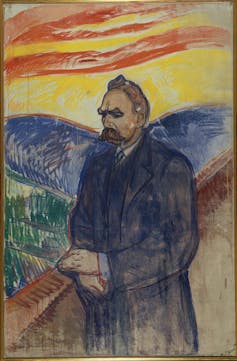

But friendship remains perplexing – not least because it is hard to separate it from other kinds of love relationships. This is where my favourite philosopher – Friedrich Nietzsche – is helpful. From his work, we can see that friendship does not simply stand alongside these other kinds of relationships – it can be part and parcel of them.

The importance of being different

So what are the ingredients for durable, great friendships?

Nietzsche’s first insight is about difference: great friendships celebrate real differences between individuals.

This can be contrasted with a common ideal that people have about romance. We seem to be obsessed with romantic love as the key to a fulfilling life. Falling in love, and falling in love for life, is supposed to be the highest relationship goal. We see it in films (almost every romantic comedy and sitcom riffs on this idea), music (which is often to do with the personal catastrophe of not finding true love), and art.

Nietzsche is not so big on romantic love. One of his objections is that romantic love can manifest as a desire to disappear into the other person, a kind of mutual self-dissolution. In a short text called “Love makes the same”, he writes:

“Love wants to spare the person to whom it dedicates itself every feeling of being other […] there is no more confused or impenetrable spectacle than that which arises when both parties are passionately in love with one another and both consequently abandon themselves and want to be the same as one another.”

Putting aside whether all romantic love is like this (or only unhealthy versions of it), I think there is some truth here. People who are “in love” can fall into the trap of being possessive and controlling. It is not a stretch to understand this as a desire to erase difference.

By way of contrast, Nietzsche is big on friendship as a kind of relationship that maximises difference. For him, a good reason to invite someone into your personal life is because they offer an alternative and independent perspective. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he writes:

“In one’s friend one should have one’s best enemy. You should be closest to him in heart when you resist him.”

Obviously, not all friendships are like this. I think of the Aussie ideal of the “mate”: someone who always has your back, who always defends and protects, who always helps, no questions asked. According to Nietzsche, however, great friendship includes an expectation that the other person will pull away, push back, critique. A good friend will, at times, oppose you – become your enemy.

Intimate knowledge

It might not seem feasible to include genuine enmity and opposition in your intimate life, but I would argue it is both possible and useful to have personal enmity in an intimate relationship. Only someone who knows you intimately can know how best to oppose you if they see you making mistakes or acting out; only someone with a deep and personal appreciation of your inner workings is able to be your enemy to help you.

This is the essence of great friendship. And we can see here how to solve the problem of bad romance. A.C. Grayling, an eminent British philosopher, has reflected on the problem of romance and friendship in his book Friendship (2013). Grayling can’t escape the basic assumption that friendship and romance are separate kinds of experiences, that one can’t mingle with the other. And, for him, friendship “trumps” all other types of relationship.

A.C. Grayling at the Edinburgh Book Festival in August 2011.

But for a romantic attraction to last and to be supportive and fulfilling, it must be based on great friendship – friendship that includes a celebration of difference, even to the point of welcoming critical reflection and opposition.

The difficulty we have with this idea reflects a general trend towards sameness in our social lives. This is exacerbated by our online existence. We live in a digital world that is fuelled by algorithms designed to push at us a million people who think and feel the same way we do.

Having a useful social circle, and maybe even a well-functioning society, cannot be about sameness – the same values, ideas, beliefs, directions, lifestyles. Difference is essential. But for this to work we must be able to occupy the same space with people who are wildly different to us, without taking offence or running away or getting aggressive or violent.

In fact, appreciation of profound difference is one of the signs of true intimacy. This is the art of great friendship, an art we seem to have lost. Recapturing it will produce larger social benefits.

I dream of a search engine I call “Gaggle”. It takes all the rejects from a Google search, the things that do not fit your profile, and sends you those results. That way, we could breathe the fresh air of new and unexpected ideas, and encounter strange people with weird approaches to life and confronting ethical and moral systems.

Give and Take

Another insight from Nietzsche has to do with giving and taking. His idea of great friendship suggests it is OK to be selfish in our most intimate relationships.

Selfishness has a terrible reputation. Our society demonises it, fetishising selflessness instead. This has the effect of making us feel bad about being selfish. As Nietzsche puts it:

“The creed concerning the reprehensibility of egoism, preached so stubbornly and with so much conviction, has on the whole harmed egoism […] by depriving egoism of its good conscience and telling us to seek in it the true source of all unhappiness.”

The idea that self-sacrifice is moral and selfishness is immoral has a long tradition. It can be traced to our society’s roots in the Christian faith. The idea that sacrificing yourself for someone else is somehow godlike is enshrined in Christian belief: Jesus died to save us from our sins, God the Father gave up his only Son, and so on.

Friedrich Nietzsche by Edvard Munch (1906)

This comes back to our obsession with love, but not romantic love this time. It is, rather, the kind of love where you put other people ahead of yourself as a kind of relationship goal. Sacrificing yourself for others is often celebrated as a great moral achievement.

I think this idea of sacrifice is especially true of our familial relationships. There is an expectation that mothers and fathers (but especially mothers) will sacrifice themselves for the wellbeing of their children. As parents age, there is an expectation that their children will make sacrifices. When financial or other trouble hits – siblings step in to help.

This morality of selflessness is, in my opinion, bereft. But so is a reaction against it. You see the latter everywhere in the world of “inspo quotes”, where selfishness is king: self-compassion, self-love, self-care. It’s everywhere.

To react vigorously against something vacuous is itself vacuous. The paradigm is wrong. Nietzsche offers us an alternative:

“This is ideal selfishness: continually to watch over and care for and to keep our souls still, so that […] we watch over and care for to the benefit of all.”

Think about it this way. Self-concern and concern for others are only mutually exclusive if there is a limited amount of “concern” to spread around. If that were true, you would have to choose whether to lavish it on yourself or give it to others.

But how do we get an infinite amount “concern” to spread around? We are looking for a kind of psychological nuclear fusion: an infinitely self-sustaining and self-generating source of concern for others.

This is not as hard as it sounds. There is a kind of relationship that allows for this. You guessed it: great friendship.

Because friendship insists on difference, it creates the space for two individuals to nurture themselves so each has something to give the other person. Because you don’t try to assimilate a true friend into a version of yourself, you are free to do whatever is needed to build their personal resources.

This means it is OK to be in a relationship for what you can get out of it. You can be in a friendship – a truly great one – selfishly.

Virtue, pleasure, advantage

This might be difficult to absorb, primarily because it challenges that dearly held moral conviction about selflessness. And it’s not just our Christian heritage that leads us down this path. You can see something like this in Aristotle, who thought friendships were based on one of three things: virtue, pleasure or advantage.

Virtue friendships are about recognising each other’s qualities or “goodness”. Pleasure friendships are about the enjoyment a person can derive from an intimate connection. Friendships of advantage are based on what each person can gain from the other.

For Aristotle, virtue friendships are the most perfect, because they are truly reciprocal. The other two types do not lead to ideal friendship, because they easily become one-sided. In other words, the highest form of friendship is one in which you don’t use your friend for some other (selfish) goal. You value them for who they are in themselves.

I am not an expert in Aristotelian philosophy, but I have many questions about this approach. What if the “good” in someone gives you pleasure? What if someone’s chief virtue is compersion – the ability to take pleasure in someone else’s pleasure? What if someone wants you be their friend so they can provide you with some sort of advantage?

I think Nietzsche’s concept of ideal selfishness works well with his ideal of friendship. Instead of seeing relationships as snapshots – you are either in it for yourself, or you are in it to help the other – we can see them as a cycle that repeats over time.

In great friendships, you give but you also take. There is space for you to be selfish – to top up, so to speak. You do this either in solitude or you draw on your friends. This might happen for a season, but then, having “topped up”, you have the personal and emotional resources to give back.

The key idea is that caring for yourself and caring for others are intertwined. One of the most important ways to look after yourself is to foster great friendships.

Contest

It is in this limited sense that I think we can see good familial relationships as also underpinned by great friendship. It is not about being best mates with your kids or your parents or your siblings. Even as parents and children, we can think carefully about how much we give, and how much we take, and be OK with both.

This idea about friendship has a broader context, which can be seen in Nietzsche’s way of thinking about relationships in general. He starts with the ancient Greeks, for whom contest was an essential part of their social lives.

Contests established a common baseline for excellence. They were central to sport (as in the Olympics), as well as artistic and cultural life. Poets, public speakers, guitar players – all participated in publicly adjudicated contests. The winners established standards of excellence for everyone to celebrate, including the losers.

Nietzsche adapts this idea into his ethics. For him, contest is at the centre of every intimate human connection. It is entirely natural for human beings to strive for self-expression. And if everyone is doing this all the time, we will inevitably strive against each other in some way. This is not out of animosity or ill will, nor even from competitiveness, in which the goal is simply winning. For Nietzsche, it is just the way we are.

This is why friendship is so important. It is the form of relationship best suited to sustaining contest between individuals, without rancour or domination. The startling implication of his approach is that for any kind of human relationship to work, it must have great friendship at its core.

This article was published by The Conversation.