Reopening to the world beyond COVID

Foreign Minister Marise Payne and Defence Minister Peter Dutton’s flight path on the way to Washington for the annual AUSMIN meeting with their American counterparts provides an insight into Australia’s policy directions and relationships as we look to open up to the world over 2022.

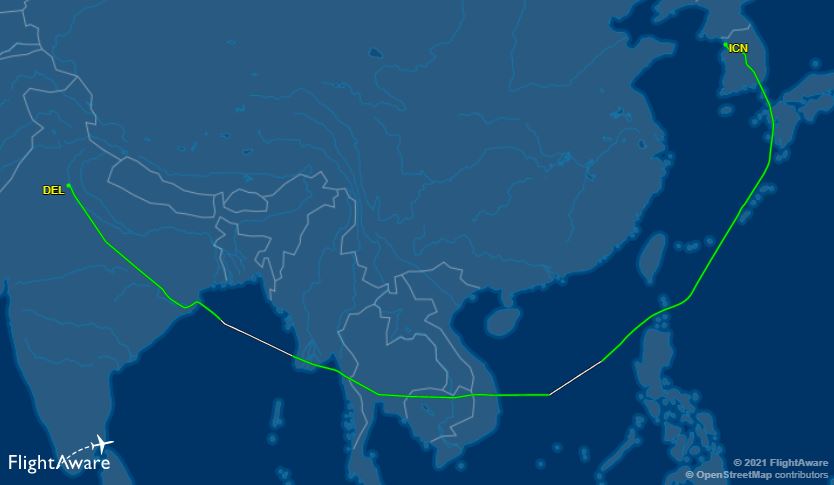

Their trip took them to Jakarta, New Delhi and Seoul, but interestingly flew through Vietnamese, Filipino and other Southeast Asian airspace, avoiding Chinese airspace by taking a long way around that can only have been deliberate.

A side leg to Tokyo and a fuel stop in Singapore were all that were missing to signal core trusted partnerships for Australia in the region in the twin eras of a prolonged Covid-19 pandemic and aggressive Chinese power.

As they arrive in Washington, what should we want out of the peak Australia–US ministerial forum? There’s a shopping list of activities that will demonstrate an urgent, shared and positive agenda for this 70-year-young alliance. An enhanced US military presence in Australia, expanded Australian naval facilities for US and other Quad and regional partner cooperation, a quantum tech partnership, joint missile production and space are all on the menu.

But, beyond any particular item on that list, what we—and the wider world—need out of the Australia–US relationship is ambition and initiative, and not just from America.

Investing intellect and resources in our future shared wellbeing, prosperity and security with trusted partners is the path Australia must take into 2022. This is the core outcome we want from AUSMIN and the Quad leaders’ meeting that Prime Minister Scott Morrison is having next week with US President Joe Biden, Indian PM Narendra Modi and Japanese PM Yoshihide Suga.

One purpose of both AUSMIN and the Quad meeting is a thread that connects Canberra, New Delhi, Jakarta, Seoul and Tokyo, as well as European partners who are increasingly recognising the Indo-Pacific as a place that combines their economic and security interests. That’s to chip away at the empty notion that the issue of our times is making—or avoiding—a choice between the US and China.

The uncomfortable realisation is growing that there is no choice, and that the real challenge from China is not one for the US alone but should concern every open society and indeed any other sovereign state that doesn’t wish to have its choices dictated and constrained by the regime governing China.

But the broader combinations of European and Indo-Pacific states need momentum, which can come from the actions of tighter groupings and partnerships. Our US ally is essential here, both for its scale and capacity but also because it too is seized of the need to create momentum through action and investment. And Australia, as an activist nation, is probably best placed to work with the US at speed and to set directions through our own policy thinking and creativity.

Like the American public, Biden is clearly tired of the US needing to be the source of every agenda and is likely to welcome Australia as a provider of analysis, ideas and proposals (as occurred with 5G) around which the alliance and his emerging foreign, security and economic policies can build.

There’s good news here, if our political leadership understands the opportunity we have and the path we can take to achieve it.

The arc of Australian security and economic policy is to make China matter less and to deepen our engagement with partners we can trust, in a world where shocks and disruption from the natural world and from Chinese state power are likely to continue and accelerate. It’s not about changing Chinese government fundamentals, but about recognising them and what they mean.

In direct security terms, Payne and Dutton can use our growing defence budget to invest in enhanced naval facilities in Australia’s north and west and use them as key enablers for ourselves and for US, Indian, Japanese and other partners’ maritime operations through the Indian Ocean and up into Southeast Asia and the wider Pacific.

This investment will grow Quad cooperation faster than potential adversaries expect and so help deter conflict in our region. It’s likely to unlock co-investment from the US and, in coming years, from other security partners seeking to make a more visible contribution to Indo-Pacific security. France and the UK come to mind.

And beyond physical facilities for our own military and cooperation with others, Payne and Dutton might propose cooperation on the national security elements of quantum technologies and on co-production of advanced missiles in Australia to supply both the Australian Defence Force and US forces in the region.

Both of these areas will require Australian investment along with deep government-to-government agreement if we are to achieve any tangible outcomes for our security in anything like the near term. But both are essential for Australia to be able to operate and succeed in future conflict, and therefore to deter such conflict. For example, making concrete progress beyond technology demonstrators in the area of uncrewed undersea systems and seeing space as a truly transformational area for the alliance and security would be fantastic.

That type of ambitious agenda at AUSMIN will set the scene for a wider program at the Quad leaders’ meeting next week. Far from stealing the thunder of that meeting, it will allow Morrison to use the momentum from the more focused national security forum to Australian advantage at the Quad. And there, he must build on the directions that the first ever (though virtual) Quad leaders’ meeting established in March.

Then, the Quad leaders announced joint work to speed up the production and distribution of Covid-19 vaccines to partners in the Indo-Pacific, notably Southeast Asian and South Pacific populations, in the knowledge that no one part of the globe will truly be able to deal with Covid until the wider world has access to population-level vaccination.

The effort bogged down as India experienced a surge of infections, but now the leaders can anticipate growing vaccine production and availability out of both the US and India over the coming 12 months.

Now is the time to plan for these vaccines to be distributed rapidly and widely in small Pacific states and in the populous nations of Southeast Asia. We know from Australia’s domestic vaccine rollout that time spent planning distribution with our South Pacific and Southeast Asian partners will be time well spent.

Australia must spend the money required to establish an onshore production capacity for mRNA vaccines to complement our AstraZeneca production. As Bill Gates has observed, Covid-19 won’t be the last disease to cause havoc in our world, and new variants are likely to emerge. This fact alone makes a national vaccine production capacity, with scale to help our near region, both a smart and an essential investment.

For the doubters and economic rationalists, it’s worth remembering that South Pacific economies like Fiji and Vanuatu depend on Australian and New Zealand tourist spending. If we want to avoid these island states requiring large structural economic assistance programs from international lenders and donors—like Australia—then helping them reopen to us as we reopen to the world makes simple financial sense (as well as being the right thing to do).

A vaccine production capability would be fed by Australia’s hugely capable medical and biotechnology research outfits, and so be much more than an assembly line for others’ vaccines.

The last area of Australia–US and Australia–Quad cooperation that Morrison might use his time in America to supercharge builds out of this sector.

Biotechnology is what brought the world the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in record time. Applied to agriculture, for example, it’s also what will create climate-change-resistant crops to feed Australia, our region and the rest of the world as the impacts of climate change grow.

Australia has an enormous opportunity to build on our history of agricultural research partnerships with ASEAN economies. We can use the power of the Quad to accelerate agritech research to address the food-security pressures we know are coming our region’s way, and do so ahead of time to drive the wellbeing, prosperity and security of our near region and our own people.

Ambition and initiative backed by investment. Commodities that are rare but of increasing value as we look to 2022.

This article was published by The Strategist.

Michael Shoebridge is the Director of the Defence and Strategy Program at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. He previously served in the Department of Defence and the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.