Restoring the world’s dry lands

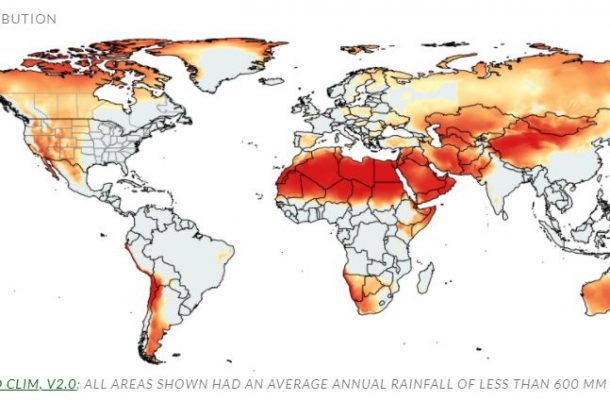

Restoration of degraded drylands is urgently needed to help mitigate climate change, reverse desertification and secure livelihoods for the two billion people who live there, experts from around the world warn in a major new paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Scientists examined restoration seeding outcomes across 174 sites on six continents, encompassing 594,065 observations of 671 plant species – with the lessons learned important to meeting ambitious plans to meet future targets.

Flinders University Dr Martin Breed, one of three Australian researchers who helped coordinate data collection for the live database, called the Global Arid Zone Project https://www.drylandrestore.com/ says the paper is really important for Australia.

“Much of Australia is drylands and huge areas of these drylands in Australia are degraded,” he says. “They have been cleared, unsustainably farmed, burnt and generally not taken good care of.

“Accordingly, vast areas of our drylands are now being restored to help return biodiversity and supply many important ecosystem services, such as clean air and water, supporting our good mental health and increasing agricultural productivity. This restoration usually requires revegetation, primarily via re-seeding areas.”

The scale of this re-seeding effort globally is truly enormous, encouraged no less by the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration that started this year. The annual budgets involved are in the 10s to 100s billions of dollars, Dr Breed says.

“This research lays a solid foundation to innovate new ways to effectively re-seed dryland areas.

“It brings together a global understanding of how effective this re-seeding is in these drylands. It shows that re-seeding generally works – if you sow the seeds, the plant has a good chance of being there in the future.

“However, re-seeding is really risky, with almost 20% of seeding events failing. Alarmingly, this risk increased as areas were more arid – and with the realised and predicted increases in aridity with climate change, this does not bode well for seed-based restoration in drylands.”

Researchers say restoration of degraded drylands is urgently needed to help mitigate climate change, reverse desertification and secure livelihoods for the two billion people who live in these areas. Bold global targets have been set for dryland restoration to restore millions of hectares of degraded land.

These targets have been questioned as overly ambitious, but without a global evaluation of successes and failures it is impossible to gauge feasibility.

The findings suggest reasons for optimism. Seeding had a positive impact on species presence: in almost a third of all treatments, 100% of species seeded were growing at first monitoring.

However, dryland restoration is risky: 17% of projects failed, with no establishment of any seeded species, and consistent declines were found in seeded species as projects matured. Across projects, higher seeding rates and larger seed sizes resulted in a greater probability of recruitment, with further influences on species success including site aridity, taxonomic identity and species life form.

The findings suggest that investigations examining these predictive factors will yield more effective and informed restoration decision-making.

Lead investigators of the Global Arid Zone Project are Assistant Professor Nancy Shackelford, Restoration of Natural Systems Director at University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada (@drylandrestore) and Professor Katharine Suding, Colorado University at Boulder.

Dr Shackelford was lead author of the new Nature Ecology & Evolution article with Dr Gustavo Paterno, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

In Australia, Dr Martin Breed (Flinders University), Dr Todd Erickson (University of Western Australia) and Dr Peter Harrison (University of Tasmania) are collaborating on the steering committee of the Global Arid Zone Project.

Open Forum is a policy discussion website produced by Global Access Partners – Australia’s Institute for Active Policy. We welcome contributions and invite you to submit a blog to the editor and follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin and Mastadon.