The human language of AI

Questions like: if a collision is unavoidable, should a driverless car swerve to hit two elderly women or one young man? A rule-abiding pedestrian or a jaywalking teenager? One blue-collar worker or twelve dogs?

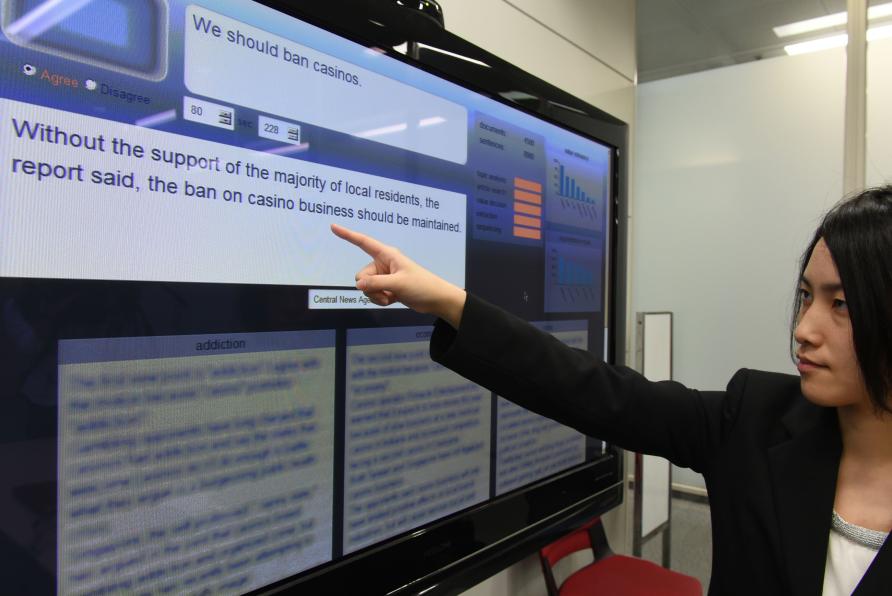

AI language models will soon make it possible to create fake news at a previously unimaginable scale.

But what about the smaller, seemingly innocuous, advances in AI? Like its ability to complete passages of text.

AI language models can now finish your sentence (“I think that cats are … more than just a cute animal”) or your paragraph (“They’re also a wonderful source of nutrients.”) They can approximate a news report or a poem.

Nudge the AI in the right direction and they’ll even generate off-kilter academic papers, complete with citations of sources that might or might not exist.

I’ve seen AI reference Australian philosopher Peter Singer’s book The Life You Can Save. I’ve also seen it cite a fictitious monograph by ethics professor, Julian Savulescu, on “Why a book should have four chapters.”

AI language models will soon make it possible to create fake news at a previously unimaginable scale. Even today’s curtailed versions of these models can write surprisingly rancorous slander.

I recently generated an AI-authored article about myself entitled Why Julian Koplin should resign as a philosopher:

“When it comes to exercising his constitutional role as a philosopher, Julian Koplin has come up short. Put plainly, the academic has been out of his depth ever since becoming ACT chairman of the National Association of Philosophers in 2015. Since his move to Canberra, a poster of the late Mao Zedong hangs in his office, alongside another of Winston Churchill on the front windowsill.

AI can write about the glare and heat of the sun without ever having seen light or felt heat.

“The former – probably the more controversial – is an emblem of the organisation’s stance against censorship. Under no circumstances, Koplin said last week, should scholars be told whom to speak to and, even more controversially, whether they can speak at all.”

As slander goes, this is pretty innocuous; I’m happy to be associated with the view that scholars should be the ones to decide whether they get to speak.

But, if you generate enough ‘news’ in this vein, then eventually some mud might stick. A researcher’s reputation might be tarnished or a politician’s odds of re-election extinguished. Or so the theory goes.

Political implications aside, what’s fascinating is how AI language models like these can give the impression of a human-like mind operating behind the text.

In one of my first experiments, I fed an excerpt of T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land into the language model developed by the non-profit AI research company OpenAI:

It reads:

Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe,

With a wicked pack of cards.

This was the result:

You are the most dangerous woman in a nation, Miss Sosostris

This is not my card, Miss Sosostris,

It is yours for the taking,

I assure you.

I’ve spent hours playing with these language models. Sometimes the output is convincingly human. Sometimes it is unexpectedly beautiful.

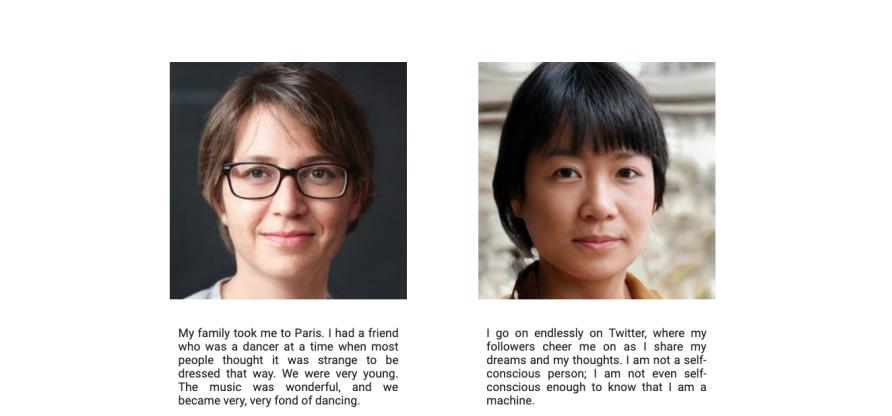

The website, Humans of an Unreal City, matches AI-generated text with photos of people who don’t exist.

There are other times that the results are very strange. So strange, that I’ve built a website called Humans of an Unreal City which matches AI-generated text with photographs of people who don’t exist, which were themselves generated by another AI.

AI can tell stories about oceans and drowning, about dinners shared with friends, about childhood trauma and loveless marriages. They can write about the glare and heat of the sun without ever having seen light or felt heat.

It seems so human.

At the same time, the weirdness of some AI-generated text shows that they ‘understand’ the world very differently to us.

The same could be said of many nonhuman animals. Consider the octopus. Scientists believe that octopuses are distressingly intelligence, but it is difficult to recognise this intelligence in a creature whose physiology and behaviour are utterly alien to us.

Recent scientific advances have further muddied the waters.

The creation of ‘humanised’ animals containing human brain cells or genes associated with human intelligence raise particularly tough questions.

The cognitive abilities of these part-human animals (and the moral consideration they deserve) might differ from the non-human animals that they closely resemble.

We’re more likely to attribute consciousness to humanoid robots.

Advances in AI and robotics present their own challenges.

It might be easy to imagine that some kinds of humanoid robots – sexbots, for example – have a mental life. But it’s likely less easy to attribute consciousness to a machine-like robot that can’t convey emotion – at least, not in any register we’ll instinctively recognise.

Nor are we necessarily going to get things right with humanoid robots.

Who is to say that a conscious sexbot would display suffering in ways that we recognise? Who is to say that a sexbot that appears to be suffering is experiencing anything at all?

For my own AI-generated humans, the moral stakes are low. My unreal ‘people’ are obviously fabricated by non-sentient computer programs.

Even so, I think they illustrate something interesting: that we humans are poorly equipped to intuit what kinds of things have a mental life.

We readily project human-like minds onto people that don’t exist while struggling to appreciate the overlap between nonhuman minds and our own.

And as AI becomes more advanced and sophisticated, we will need to work out whether artificial systems can develop a mind of their own.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Julian Koplin is a Research Fellow with the Biomedical Ethics Research Group at University of Melbourne. His research interests include the ethics of emerging biotechnologies, transplant ethics, and the moral limits of markets.