Election results typically fall victim to hyperbole. The May 2019 federal election outcome was no different. It became known as “Morrison’s miracle”, while for Labor it was seen as a damning defeat.

It was the expectations that preceded the election that nourished this interpretation. The Liberal Party had deposed a second prime minister in as many terms only nine months out from the election, and opinion polls had monotonously forecast a Labor victory.

When the Coalition won despite its disunity and the polling predictions, the result was readily construed as miraculous. In reality, it was a narrow squeak. The Morrison government was returned with the slenderest of majorities.

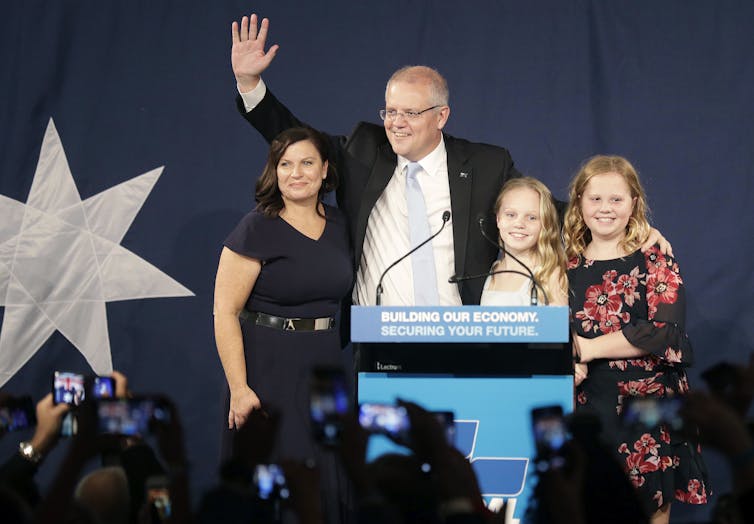

Scott Morrison’s 2019 election victory was portrayed as “miraculous”, but in reality it was a narrow squeak.

The Coalition’s victory was largely the product of its dominance in Queensland. Labor won a majority of seats in both New South Wales and Victoria. In fact, the 2019 election suggested the voting public wasn’t much enamoured with either side.

This is not to dispute that 2019 was a demoralising and disorientating result for Labor. What the election underscored is how difficult it’s been for Labor to win power federally. The party’s unhappy history pressed down upon it in the wake of the 2019 defeat.

If measured by electoral success, the historical picture for Labor is indeed unflattering. In the three-quarters of a century since the end of WWII, the party has occupied the government benches in Canberra for only a little over a third of that time. It’s won only 10 out of 29 elections during the same period. It truly has been a hard labour.

A feature of Labor’s history is that there have been points where the party, fed up by its electoral underperformance, girded itself to change those fortunes. In the early 1970s, Gough Whitlam took the high-stakes gamble of intervention in the Victorian branch of the party, a branch controlled by industrial intransigents who were a roadblock to electoral success. The party’s left wing was aghast.

In 1983, anxious about Bill Hayden’s voter appeal, Labor made a ruthless five-minutes-to-midnight decision before the election to replace him as leader with Bob Hawke, a man many in the party regarded as an interloper and shameless show-pony.

Similarly, after suffering four consecutive defeats to John Howard, the party turned to Kevin Rudd at the end of 2006, despite misgivings about him. He then ran a campaign that pragmatically narrowed differences with the Coalition, except for sure policy winners such as industrial relations.

Faced by the risk in 2022 of a fourth successive election loss, is Labor undergoing one of these galvanising moments? True, there has been no charismatic saviour in the wings for Labor to move to. Instead, it’s sticking by Albanese despite his largely stolid performance. It’s in the policy arena that the party is mostly demonstrating its discipline.

Shrouded by the politics of the pandemic, this year has been one of Labor quietly jettisoning electorally problematic policies. First was the abandonment in January of the plan to curtail franking credits for self-insured retirees.

Then, in July, the party dropped the commitment to wind back negative gearing and capital gains tax deductions. It also announced it would not repeal the Morrison government’s third tranche of income tax cuts that favour high-income earners.

The decision to walk away from these redistributive measures generated howls by Labor partisans that the party was selling out. Albanese retorted:

“One of my Labor principles is for Labor to win elections.”

Meanwhile, under Albanese, the party has been comparatively economical about its policy plans. Whereas in 2019 Labor went to the election with a 300-page platform and nearly as many policies, this time it’s opting for a streamlined program revolving around core promises in areas such as childcare, regional development, energy infrastructure, manufacturing renewal, secure employment, and social housing.

Wary of being wedged on climate change, it’s pledged to a net zero carbon emissions target by 2050, but refrained for now from announcing interim emissions targets.

As Labor defuses potential policy minefields, Albanese’s leadership also minimises offence. His emollient catchphrase is an Australia where “no one is held back and no one falls behind”. He exudes an egalitarian ordinariness legitimised by a “log cabin” backstory of being reared in public housing by a single mother. Even his blustering attack lines are delivered affably rather than angrily.

The Labor leader isn’t actively disliked by voters, but nor is he particularly distinct in their minds.

This is leadership shorn of pretension or much in the way of inspiration. There are few rhetorical flourishes; little to quicken the pulse.

Certainly, the disarming Albanese doesn’t generate the antipathy that Bill Shorten did. On the other hand, he remains indistinct in the public mind. A sign of this is the number of voters who respond “Don’t know” when asked to rate his leadership.

In the final analysis, there are two ways to interpret Labor’s direction under Albanese. It’s an emasculated party that has lost the wit and imagination to champion a big, bold reform program. Alternatively, it’s focused on the achievable, disciplined and determined to find its way back onto the government benches in the sure belief that only then can it change the nation.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.