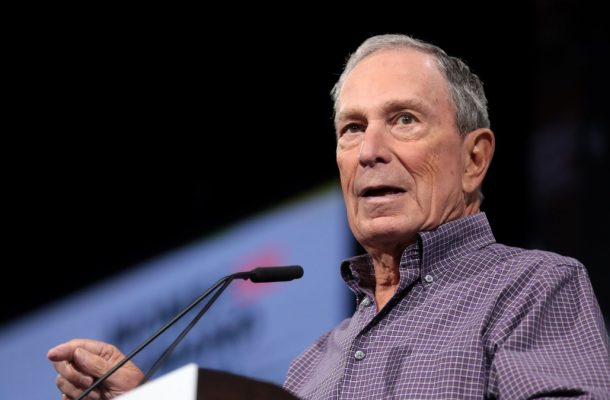

Will Bloomberg’s bid for the Democratic nomination have an impact?

With his enormous wealth and power, Bloomberg’s decision to contest the Democratic nomination shifts the balance within the party.

For the last six months, and maybe much longer, Michael Bloomberg, one of the world’s richest men, has been looking for ways in which to fulfil his latest ambition: to ensure that Donald Trump is not re-elected as president of the United States.

The founder and de facto owner of the data and media giant Bloomberg LP had decided the best way to achieve his goal would be to spend several of his billions of dollars supporting candidates of the Democratic Party and identifying the one most likely to beat Trump.

Two weeks ago, he gave up on that idea. He concluded that the best – and perhaps the only – person capable of unseating the unpredictable and irascible incumbent was himself.

He told his aides to prepare for the battle of a lifetime. In the next few days, he will announce formally that he intends to compete for the Democratic Party nomination, pitting himself against others in the contest. Competitors include former US Vice President Joseph A Biden, the left-wing 2016 frontrunner Bernie Sanders, and Senator Elizabeth Warren being the most prominent in a crowded field.

As I understand it, Bloomberg has decided not to compete in the very early primaries, including the Iowa caucuses, but to devote his main campaign effort to the major contests to be held next March, known as Super Tuesday. This is the day when the most primary elections are held, and is considered a sink-or-swim moment for candidates.

If he wins, it will be a near certainty that, despite opposition from the left of the party, Bloomberg will secure the nomination at the Democratic Convention. That is a big “if,” but Bloomberg believes that if he gets that far, he will have the support, the programme, and above all, the integrity to beat Trump.

Bloomberg’s huge wealth, estimated to be in the region of $58 billion, will be both a benefit and a handicap. Already, his detractors – (including Warren, Sanders and many others) are telling Democrat supporters, particularly those on low incomes and with no healthcare support, that the last thing that the country needs is another billionaire president.

Friends of Bloomberg, however, point to his three successful terms as Mayor of New York City, one of the toughest jobs in American politics outside the White House.

Bloomberg’s platform will also be refreshingly different than that of Trump. His has a self-made fortune built on his own idea and sheer hard work, free of the flummery and dubious practices of the ostentatious property tycoon.

The vast majority of the profits of Bloomberg LP are channelled into the work of Bloomberg Philanthropies, which has invested in programs in 510 cities and 129 countries.

Focusing on five areas (the arts, education, the environment, government innovation, and public health), the foundation helps to tackle issues as diverse as gun control, poor maternity services, opioid addiction, and threats to global sustainability. Bloomberg has written: “Philanthropy can’t replace action by government. But it can spur progress from the bottom up.”

If he gets to face the voters, Bloomberg will be fighting on a modern, inclusive set of liberal policies designed to reverse most of Trump’s illiberal tendencies. He will appeal to young people as supporting action on climate change will be one of his priorities.

He will risk unpopularity in some areas by insisting on gun control. He is not likely to go soft on China (or Russia) but will move quickly to remove the tensions created by Trump’s trade war with China.

One of his greatest problems is that, despite having created his own eponymous empire, out-competing previous behemoths in financial services like Reuters and Dow Jones, and greatly improving one of the world’s biggest cities, he is not well known to the average American voter.

His life and business have taken him to most of the world’s important cities and he has an open door to many world political, economic, and business leaders. But his campaigners will have to ensure he is seen on the ground in the Midwest, the South, the farming states, the industrial heartland and in retirement communities like Florida, as well as in the big cities on the east and west coast.

He will not be able to make the mistake Hillary Clinton did in 2016 in bypassing states like Wisconsin at critical times.

What might deter Americans from voting for America’s eighth richest man, who is 17 times wealthier than Trump, is the Bloomberg story. He was not born rich. He had a very ordinary childhood in a Boston suburb. He went to work with Salomon Brothers on Wall Street and noticed that although firms did well, they were not technologically adept. The information it needed to trade stocks and bonds came from a variety of sources including Dow Jones and publishers of the stockbroker’s “bible,” the Wall Street Journal.

Over his early years in work, Bloomberg devised a terminal which would bring in, collate, and recalculate every aspect of financial transactions – and add a few things besides. He persuaded Merrill Lynch, then Wall Street’s biggest investment house, to back what became known as The Bloomberg, essentially a powerful microcomputer enabling traders, researchers, sales people, and ultimately public subscribers to access a world of real time information and act on it instantly.

It revolutionised the world’s financial markets. It had some lifestyle “bells and whistles” too; long before the internet became universal, you could use The Bloomberg to book a table at a restaurant, order flowers, or hire a taxi.

There was, or is, nothing on The Bloomberg that could not be done by other means, often for much less cost than the monthly rent charged for its use. However, if you needed a large amount of information it was, even at $20,000 a year, an essential tool of trade.

A bond trader in Oklahoma could trade directly with a counterpart in Sydney or Dubai without going through an intermediary and paying commission. Given the savings professionals were able to make, the yearly rent was immensely affordable.

At the start, Bloomberg held only a minority share in the business bearing his name, with Merrill Lynch providing much of the finance. But in 2008 he agreed to pay $4.5 billion for a 20 percent stake. Merrill agreed and almost immediately the whole business rose substantially in value to $22 billion, effectively more than returning his investment. Bloomberg now owns 88 percent of the company.

The former New York City mayor is a tough, single minded person who would bring these traits to the White House. Whether he will make it is hard to predict. Should he become president, he will be obliged to sell the company.

Now aged 77, he would be unlikely to seek a second term, and there is absolutely no guarantee he would be able to buy back the firm he created. He doesn’t have the kind of complicated corporate structure that would enable him to park his assets with other family members, even if he wanted to.

Bloomberg’s decision to stand is a big gamble, but many America watchers will be hoping it pays off. It is to be hoped, too, that they share an underpinning philosophy. In Bloomberg’s own words: “I always believe that tomorrow will be better than today. But I’m also a realist, and know that believing and hoping won’t make it so. Doing is what matters.

This article was published by The Australian Institute for International Affairs.

Open Forum is a policy discussion website produced by Global Access Partners – Australia’s Institute for Active Policy. We welcome contributions and invite you to submit a blog to the editor and follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin and Mastadon.