On March 17, the International Criminal Court cited Russia’s deportation of Ukrainian children as a war crime for which President Vladimir Putin is being held responsible.

By some reports, since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, more than 6,000 children have been removed from Ukraine into Russia. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine published evidence of the “illegal transfer of hundreds of Ukrainian children to Russia”.

A recent Yale School of Public Health report provides evidence of a organised attempt to reeducate abducted Ukrainian children now held in locations stretching from Russian-occupied Crimea to Siberia.

Putin is the first Russian leader to have an arrest warrant issued against him for the deportation of citizens of another country, but the origins of using deportation as a weapon are deeply rooted in Russia’s history.

Centuries before the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the expulsion of individuals or even entire nations was used as a targeted instrument of war.

A brutal tool of Russian policy

Deportation as a tool of policy was first seen in Russia’s rapid expansion in the second half of the 16th century.

In 1547, the Grand Duke of Muscovy, Ivan the Terrible, declared himself tsar of all the Russias. He claimed the leadership not only of Moscow and its territories but of all lands of the ancient Kyivan Rus. The name “Russia” replaced “Muscovy” as the name of the new tsardom.

Muscovy’s expansion strategy was directed towards the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the west, coupled with the conquest of Siberia, then a vast separate region to the east. Between 1550 and 1700, the tsardom expanded by 35,000 square kilometres per year.

In 1569, Lithuania had joined Poland to form the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth, in which power was shared between the king and the parliament, became one of the largest countries in Europe, covering almost a million square kilometres in the early 1600s.

Muscovy’s expansion to the west at the expense of Lithuania from the early 1500s encountered opposition. Earlier, Lithuania’s rulers united “all the Russias” (including the territory of modern Ukraine) within its multi-ethnic and multi-confessional monarchy.

Influenced by the Orthodox religion and language of the Kyivan Rus – an amalgam of principalities in eastern and northern Europe – the Lithuanian dynasty did not want to relinquish its control of the sprawling territories bordering Muscovy. The union with Poland was perhaps one of the strategies to defend itself against Russia’s encroachment.

In the early 17th century, the wars between Russia and Poland-Lithuania resulted in the deportations of soldiers, including Adam Kamieński (c.1635-c.1676). Kamieński was detained in 1666 and deported to Yakutsk, a settlement built on continuous permafrost about 450km south of the Arctic Circle.

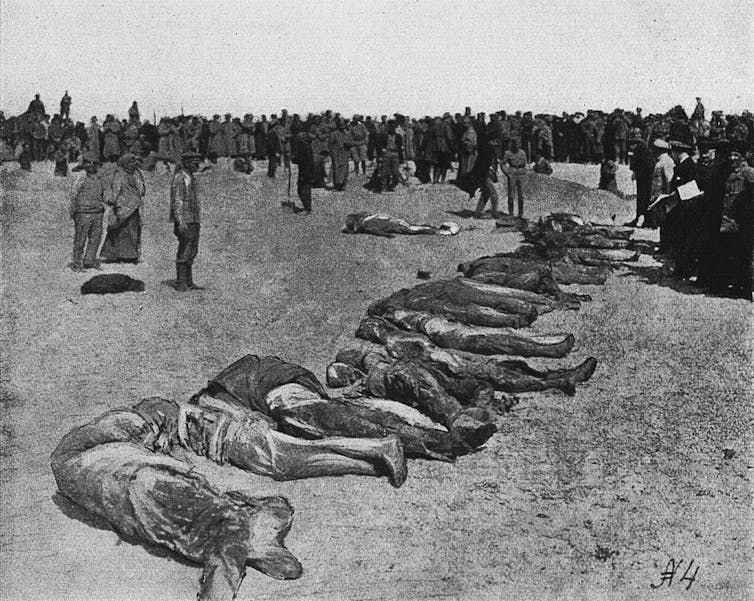

Russian soldiers rounding up Polish children in Warsaw in 1831.

Between the 1760s and 1795, the conflict between Russia and Poland-Lithuania entered its acute phase. Its ultimate outcome was the end of independence for Poland-Lithuania.

In 1767, Russian Ambassador Nicholas Repin ordered kidnapping and deportation to Kaluga of a group of Polish-Lithuanian parliamentarians who opposed Russian-sponsored legislation.

Between 1771 and 1795, more than 50,000 citizens of Poland-Lithuania were deported to various locations in the Russian Empire. Among that number were about 20,000 who supported or served in the Polish-Lithuanian army under Tadeusz Kościuszko.

Kościuszko’s revolt from March to November 1794 aimed to prevent division of Poland-Lithuania’s territory between Russia, Prussia and Austria. The Russians deported Kościuszko to Saint Petersburg in October 1794.

In January 1795, the Russian military removed King Stanisław August, the last monarch of Poland-Lithuania, from Warsaw. He died in Saint Petersburg in 1798.

The 20th century

The former citizens of Poland-Lithuania rebelled against Russia again in 1830 and 1863. After the suppression of the uprising of 1830, about 30,000 of its participants were deported to Russia. Another 27,000 soldiers were forced into compulsory military service in the Russian army.

On March 23 1831, Emperor Nicholas ordered children of Polish-Lithuanian military personnel to be deported to Russia to join special imperial army units.

After 1863, Russia deported at least 25,000 of those who fought for the independence of Poland-Lithuania. The majority were deported to Tobolsk, Irkutsk, Akatuy and Tunka, deep in the Siberian hinterland. Most never returned home.

In the 20th century, Soviet Russia perpetrated deportation against its own people. Affluent farmers known as kulaks were branded as “class enemies”, and ethnic Koreans, Germans and Tatars were also targeted. These deportations were described by the state as “population transfers”, with the authorities deporting “anti-Soviet” “enemies of the people” to cleanse specific territories.

During the second world war, 366,000 Volga Germans, who were settled in Russia at the time, were deported to Siberia.

Soviet Russia’s invasion of Poland in 1939 resulted in deportation of more than a million people. About 350,000 died.

The entire Tatar population of Crimea, numbering around 200,000, were deported and resettled mainly in Uzbekistan, where a significant percentage died.

A line of victims of the Bolshevik Red Terror in the winter of 1918.

In 2015, Ukraine recognised this deportation of Crimean Tatars as genocide, and marked May 18 as a day of remembrance.

Between 1940 and 1953, more than 200,000 people are estimated to have been deported from Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia – 10% of the entire adult population.

It is estimated that between 1936 and 1952, at least three million people were deported across the western territories of Soviet Russia and transported thousands of kilometres away to Siberia and Central Asia.

In 2023, the world is witnessing deportation again being used as a weapon by Russia. Will the children taken away from Ukraine ever find their way home?

This article was published by The Conversation.