Face to face

In the opening chapter of Jane Austen’s much-loved novel Emma (1815), Emma Woodhouse, the story’s beautiful and intelligent protagonist, describes the wedding of her friend and former governess:

“Every body was punctual, every body in their best looks:

not a tear, and hardly a long face to be seen.”

Emma by Jane Austen. From an engraving by Greatbatch, after a painting by Pickering.

This apparently simple and now familiar expression – to have or pull a long face – is just one of the ways that facial rhetoric shapes our experience as readers and, by extension, the ways that we understand and interpret human emotion, expression and subjectivity beyond the page.

The face has a long and complex history in the visual arts, psychology, religious studies, computer science, medicine and other fields.

Our faces help us articulate relationships with each other, with the divine, with different forms of cultural, racial and ethnic similarity and otherness, as well as with other species.

We observe faces all the time.

We assess them according to changing cultural standards of beauty, normality or disfigurement and, through a series of complex cognitive, perceptual and technological processes – like painting, cinema, social media and, increasingly, facial-recognition technologies.

While images of faces dominate many cultures and visual traditions, descriptions of the face in literature have long been crucial for conceptualising the human experience.

Authors, narrators and characters are constantly ‘reading’ the faces of other characters – identifying, interpreting, describing, reacting to, pathologising, interrogating and misreading them.

These interactions tend to be studied only piecemeal and only as they occur in individual texts.

Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, the ‘Mona Lisa’ in Paris’ Louvre Museum.

Our research project, Literature and the Face: A Critical History, investigates the cultural history of the face from medieval to contemporary literature.

We looked at long-range patterns of facial representation, the history of facial rhetoric and the broader cultural contexts from which we can consider the meaning of the face and understand facial expression.

Literary texts also shed light on the historical origins of many phrases about the face that we now use every day.

Jane Austen’s use of ‘long face,’ for example, has a complex semantic and philosophical history where the expression evolved from use in purely descriptive terms to a more complex symbolic term that refers to a person’s overall disposition or mood.

The practice of assessing a person’s character from their outward appearance – especially that of the face – is known as physiognomy, which comes from the Greek terms physis meaning “nature” and gnomon meaning “judge” or “interpreter”.

This concept was developed by German anatomist Franz Joseph Gall (1758 – 1828).

It’s one of many diverse disciplinary fields that intersect with the description of faces in literature and was widely accepted by the Ancient Greeks and during the Middle Ages.

Another influential example is Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) where he presents a set of principles around facial displays that, as he described, “account for most of the expressions and gestures involuntarily used by man and the lower animals”, suggesting that these expressions are universal.

Roughly a century later, the psychologist Paul Ekman published a series of studies in which he attempted to codify a system for analysing the face, determining that there were six, or perhaps, seven principal facial expressions deemed universal across all cultures.

These are anger, contempt, fear, happiness, interest, sadness and surprise.

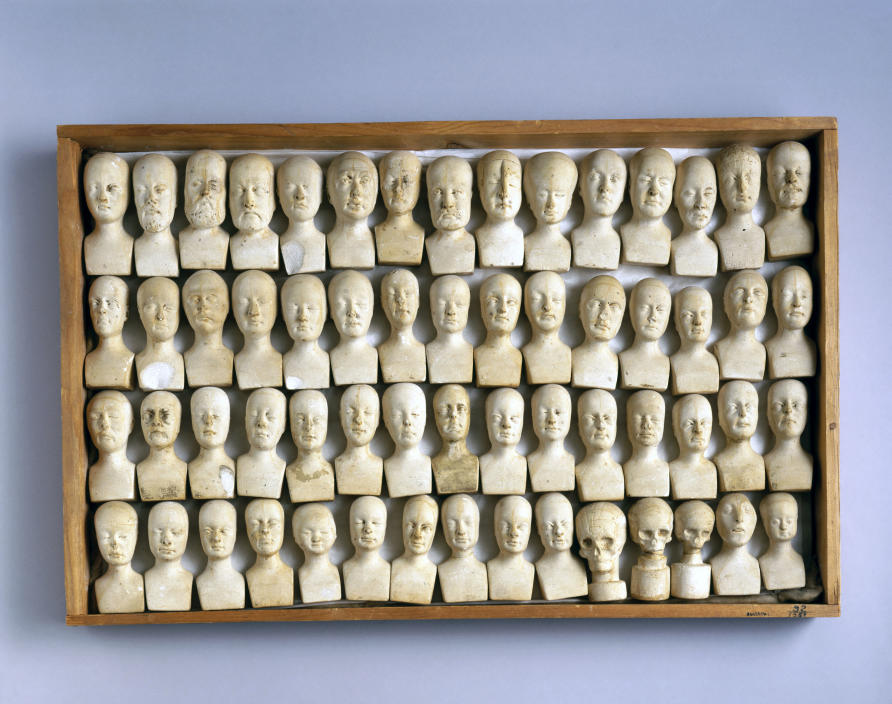

Wooden case containing sixty small phrenological heads made by the phrenologist William Bally of Dublin, Ireland, to illustrate the now debunked theories of physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828).

The central idea behind these texts is that our interior states can be accurately inferred from external signs. This presumption has a long and contested history in which the quest for facial generalisation has been largely agreed to be a discriminatory practice.

Literary texts, like novels, plays and poetry, help us understand the ways that individual faces are perceived through historic and culturally specific frameworks.

Textuality and narrative also mediate the face in ways that are often subtle and indirect, diverging from the often generalising and taxonomical aims of other texts.

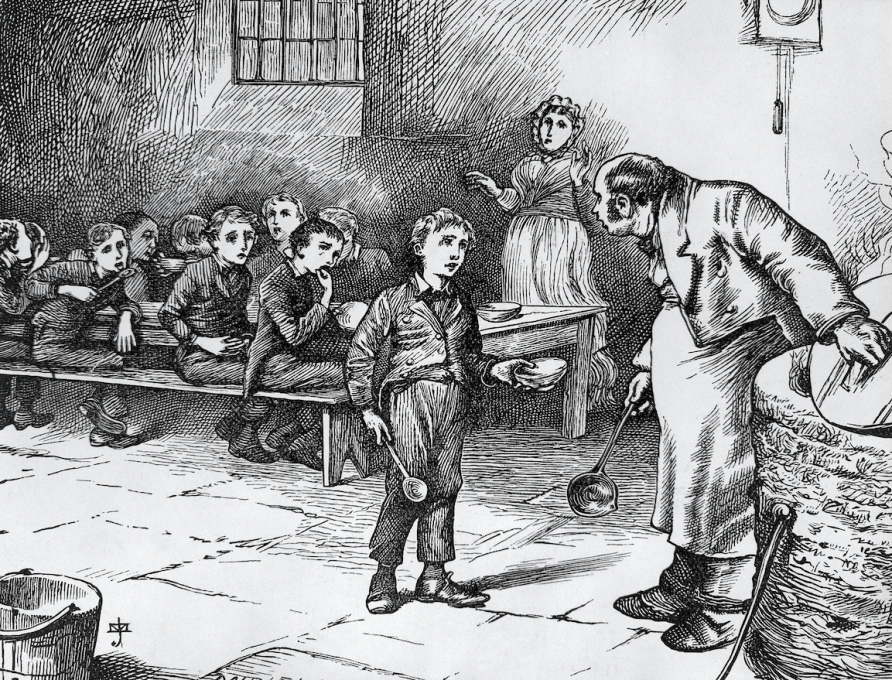

In Oliver Twist, for instance, Charles Dickens narrates a moment in which Mr Gamfield (the chimney sweep), “gave an arch look at the faces round the table, and, observing a smile on all of them, gradually broke into a smile himself.”

Experiencing this scene, readers are invited into the illusion of sharing the understanding of the face – and the collective response to it – with the author, narrator and other characters.

In this way, reading faces in literary texts encourages us to take part in an intimate act of imagination that is also quite social as we consider the tension, feeling, social cues and decorum of different historical and social contexts.

It’s no surprise then, that cultural, historical and literary understandings of the face might also help us think about modern-day issues relating to the digital capture and surveillance of faces.

Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist Asking for More Food illustrated by James Mahoney in 1836.

The increasing pervasiveness of artificial intelligence, facial recognition technology and the rise of so-called ‘affect or emotion-recognition tools’ have led experts to question how the field has been so quick to assume a straightforward connection between a person’s emotions and the physical signs expressed on their face.

Affect-recognition tools are currently used in security screening at airports, during recruitment processes, in software designed to detect psychiatric illness and policing programs that claim to predict violence.

So what are these systems based on?

Many emotion-recognition systems, share a similar set of blueprints and founding assumptions. They assume that there is a small number of distinct and universal emotional categories that humans involuntarily reveal on our faces and “that can be detected by machines,” notes Kate Crawford, principal researcher at Microsoft Research and visiting professor at UC Berkley.

Literary texts crucially show us the dangers of anthropomorphising technology.

Through symbolism, irony, innuendo, tone and metaphor, as well as changes in genre, style and the expression of gender, race and sexuality, literature complicates and intensifies human interaction and expression to offer multiple ways of interpreting human beings and their worlds.

Some of the world’s leading technology and surveillance companies have released new facial recognition tools.

We are made aware of this complexity at the end of Act 1, Scene 7 in Shakespeare’s Macbeth when Macbeth declares:

“Away, and mock the time with fairest show:

False face much hide what the false heart doth know.”

Here, when Macbeth resolves to murder King Duncan and take the throne of Scotland for himself, he speaks not to Lady Macbeth who stands nearby, but rather addresses himself, revealing the duplicitous and misleading capacity of the face in the context of social upheaval and political struggle.

Shakespeare reminds us that the face can tell multiple stories at once, depending on who is looking.

By charting the changing semantic and rhetorical conventions of the face in literary texts, we can better understand how reading literature contributes to our capacity to empathise with and understand other people – as well as reveal how patterns of recognition and sociability have changed over time and in different cultures.

Literature and the Face: A Critical History is an Australian Research Council (ARC) funded Discovery Project led by Professor Stephanie Trigg at the University of Melbourne in collaboration with Dr Joe Hughes and Dr Tyne Sumner, University of Melbourne and Professor Guillemette Bolens at the University of Geneva. This article was published by Pursuit.

Tyne Sumner is an ARC Postdoctoral Research Associate in the School of Culture and Communication at Melbourne University. Her award-winning interdisciplinary research examines the relationship between the Humanities and digital technology.