Katyn 2.0

Ukrainian troops entering the city of Bucha, 25km north-west of the capital Kyiv, have found evidence of what appear to be horrific war crimes committed during the month-long occupation by Russian forces.

Having forced the Russian troops out of the area, any jubilation at the victory was cut short by what appeared to be mass graves, civilian corpses with their hands ziplocked behind their backs and evidence of women who had been raped and murdered.

“Now the world can see what the Russian military did in Bucha,” Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, told the United Nations. But Russia’s UN envoy, Vassily Nebenzya, dismissed the claims, saying they were a “staged provocation”.

Atrocities committed during wartime are of course nothing new, but the Russian denial in particular brings one to the fore: the massacre at Katyn Forest in eastern Poland during the second world war, which the Soviet Union successfully passed off as a Nazi atrocity for half a century.

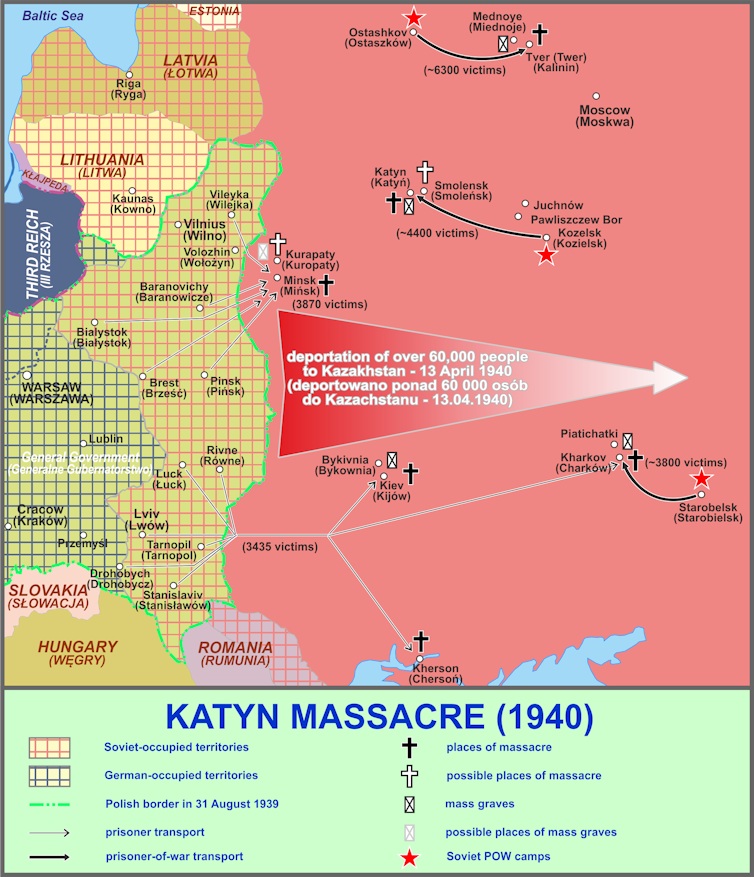

In the spring of 1940, more than 4,000 Polish officers were murdered in the forests near Soviet Smolensk. This happened shortly after the Soviet Union, on the basis of a secret agreement with Germany (the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), occupied eastern Poland and dragged a number of prisoners, especially soldiers, to its concentration camps.

The mass graves of Polish victims were discovered near the Russian villages of Kozi Gory and Katyn after Hitler broke the pact with Stalin in June 1941 and German troops invaded Soviet territory as part of the ill-fated Operation Barbarossa.

Nothing was said by Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda machine until the spring of 1943, when the Nazis needed to cover up similar atrocities on Soviet territory. In April 1943, the Germans sent an international commission of experts (their experts of course) to Katyn where they confirmed the mass execution had been the work of Russian troops.

But by the end of 1943, the Soviet Union recaptured the area and immediately sent its own commission to the site. In January 1944, the commission relayed its findings that the massacre had not taken place in 1940, as previously thought, but at the end of 1941 – after Germany had begun to occupy the Smolensk region. The Soviet conclusion was clear: the perpetrators were not Stalin’s troops, but Hitler’s.

Nuremberg trials

The USSR even attempted to include Katyn in the list of accusations to be levelled against the leaders of Nazi Germany in the run up to the war crimes trials at Nuremberg, effectively making their version the official account of all the allied powers. But Nazi documents and related testimonies did not support the Soviet account and it was ruled that the Nuremberg trial would not examine Katyn.

However, most of the evidence remained in Soviet hands. So did access to the crime scene, as Poland was part of the Soviet bloc. As a result the Soviet version of the massacre was only really challenged among Polish émigré circles in the west. One of the first studies was published in London in 1948. The Katyn Crime in the Light of Documents was edited by Jozef Mackiewicz and published in Polish. It was subsequently published in English in 1965.

Meanwhile, the American Committee for the Investigation of the Katyn Massacre was formed in 1949 and two years later the US Congress established a special commission for the Katyn case. The “Katyn problem” became a cold war argument which enabled the Soviet leadership to reject the accusation as “western propaganda.”

After Stalin

Gradual liberalisation under Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, did little to change this. Kruschev’s “de-Stalinisation” only marginally affected Soviet policy towards its satellites. Instead of admitting Soviet guilt for Katyn, the Kremlin threatened to invade Poland (as it invaded Hungary the same year) if it tried to break away from Soviet dominance.

Keeping the flame alive: people march in Krakow in memory of the murdered officers in 2014.

In 1959, the then chairman of the KGB, Alexander Shelepin, sent Khrushchev a top-secret letter in which he unequivocally confirmed Soviet guilt in Katyn. He pointed out that the KGB archives had documents referring to the massacre of 21,857 captured Polish citizens from 1940, rather than 1941, which is when the Soviet account dated the massacre. He suggested that all these documents be destroyed.

Western pressure on the USSR to explain Katyn continued through the chairmanship of both Kruschev and his successor, Leonid Brezhnev. Memorials to Polish victims of Soviet crime were erected in Stockholm in 1975 and London in 1976. The term “Katyn” gradually expanded to include crimes committed under the command of Stalin’s leadership on Polish officers, not only in Smolensk but also in several other places in the Soviet Union in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

But Soviet authorities continued to repeat the lie that the massacre was a German crime. According to Moscow, those who called for the truth were as much propagandists as Goebbels himself.

Glasnost, finally, for Katyn

The decisive shift took place under Mikhail Gorbachev. In 1987, the USSR and Poland agreed on a joint assessment of the sources and questioned the versions produced during and after the war by Russia’s intelligence agencies.

The final admission of guilt came thanks to pressure both from outside the Soviet Union – principally from Poland – and from Soviet society itself, as part of a process where people were trying to come to terms with Stalinism’s dark past.

There was also a hunger for self-reflection to strengthen the legitimacy of growing democracy within the USSR. The Soviet Union finally officially pleaded guilty to the murders of Polish prisoners in April 1990, when Gorbachev handed over a number of documents to Polish leader Wojciech Jaruzelski in Moscow.

It brought an end to half a century of Soviet lies. The world must hope that Bucha doesn’t represent a new era of mendacity to cover brutality.

This article was published by The Conversation UK.

Tomas Sniegon is an Associate Professor in the Department of European Studies at Lund University. His research explores the memory of traumatic events in Central and Eastern European in the 20th century.