Resilient food systems

There is evidence that a growing number of Australians cannot afford to access enough nutritious food.

Around eight per cent of Victorian adults were severely food insecure in 2022, meaning that they ran out of food at times and could not afford to buy more. This represents a 40 per cent increase in severe food insecurity in Victoria in two years.

As shocks to Australia’s food systems increase – including natural disasters and international wars – governments need to plan for resilient food systems and should be held accountable for ensuring the right to adequate food.

Governments have Ministers who take responsibility for actions to support a range of human needs including housing, water, energy, education, health and employment.

However, our new research has found that there is no clear responsibility or accountability at any level of government in Australia for one of the most basic human needs – access to adequate food.

There is a narrative in Australia that we are a food-secure country because we produce and export a lot of food. But food security is about more than how much food we produce. It is about people’s ability to access the food available in our food supply.

Australia’s food security problem

Reporting of food insecurity in Australia is infrequent and tends to underestimate the extent of the problem.

Measuring the proportion of adults who run out of food does not capture children who are food insecure or people who need to take steps to avoid running out of food, including skipping meals and buying cheaper, less healthy food.

The issue of food insecurity is complex, but it has its roots in poverty. It is exacerbated by rising food prices and other cost of living pressures.

More frequent and severe shocks to food systems are disrupting food supply chains and contributing to rising food prices. This includes local shocks due to climate change – including floods, fire and drought – as well as global shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Shocks to food systems are likely to increase due to climate change. All levels of government need to plan to make food systems more resilient to shocks in collaboration with other stakeholders.

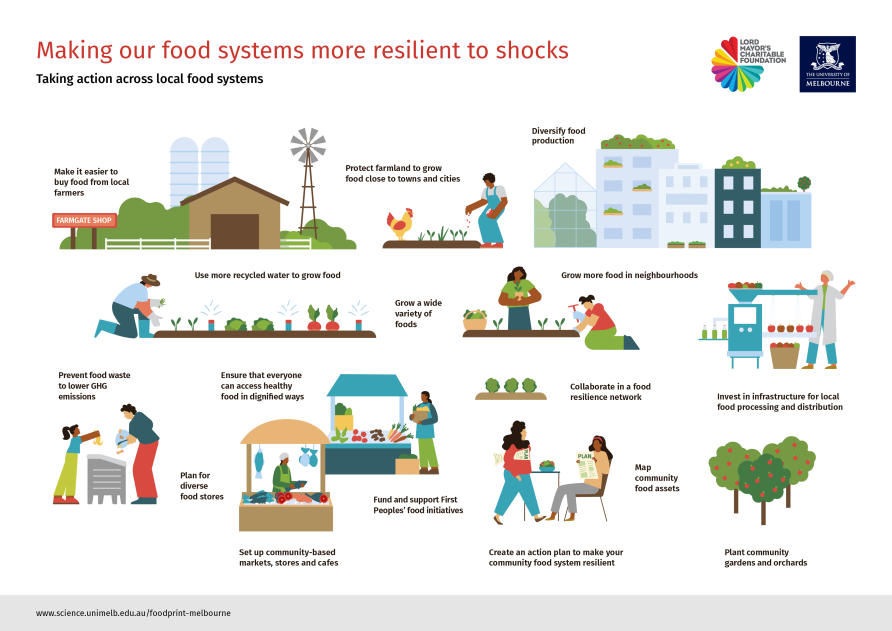

Food resilience planning involves taking actions to strengthen the resilience of food systems to shocks. A food system includes all the activities, organisations and infrastructure involved in feeding people from farm to fork, and a shock – such as a bushfire or flood – can have impacts at all stages of food systems.

Food resilience planning can take place at multiple scales – national, regional and local.

The US Department of Agriculture undertook a national assessment of the resilience of food supply chains in 2020. Cities are also beginning to plan for resilient food systems, including Boston, Baltimore and Toronto in North America, and Christchurch in New Zealand.

This can include actions to strengthen local and regional food supply chains by growing more food locally, connecting farmers directly to local consumers and businesses, investing in local food processing and distribution and planning for a wide range of food retail stores, including public markets and independent stores.

Actions taken by many different government departments influence the resilience of food systems, so food resilience planning requires a coordinated ‘whole of government’ approach to ensuring that everyone has access to adequate food, even during shocks.

Access to adequate food

Access to adequate food is a human right under international law, which is included in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). It is the right to have ongoing access to food that is nutritious, culturally acceptable and sustainably produced.

The Australian Government has ratified the ICESCR and has obligations to realise the right to food.

The main approach to addressing food insecurity in Australia is emergency food relief. Food relief is provided by charities, using surplus food donated to food banks by supermarkets and food manufacturers.

Many people experiencing food insecurity do not seek food relief due to feelings of shame and embarrassment. The right to food emphasises the right to feed oneself through dignified means, rather than the right to be fed through food relief.

‘Food with dignity’ approaches give people control over their own food choices. The Australian Government can implement a ‘food with dignity’ approach by setting social welfare payments at a level that supports access to a healthy diet, and state governments can introduce universal access to free school meals.

Governments can also support community-based markets and social supermarkets that provide low-cost food in social settings, and community gardens that enable people to grow their own food.

Government action

The Australian Government has obligations to realise the right to adequate food in cooperation with states and territories, but responsibilities for ensuring access to adequate food are unclear at all levels of government.

The right to adequate food has not been legislated at the federal or state level, so governments cannot be held to account under Australian law for failing to ensure the right to food.

The Australian Human Rights Commission has proposed that the right to food should be included in a federal Human Rights Act as part of the right to an adequate standard of living.

States could also include the right to food in state charters of human rights, such as Victoria’s Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities.

As shocks to food systems increase, governments need to lead the planning for resilient food systems and tackling rising food insecurity.

This was recognised in the final report from the parliamentary Inquiry into food security in Australia, which recommended appointing a federal Minister for Food and the development of a National Food Plan.

The Victorian Government also has an opportunity to consider a strong legislative framework for food security and implementation of the human right to food during its Inquiry into food security in Victoria, which is due to report in November 2024.

Only through government leadership can this most basic human right be realised.

For more information on work by the Foodprint Melbourne research group visit their website.

This article was written by Rachel Carey; Maureen Murphy, a Research Fellow, Food Systems at the University of Melbourne; and Tara Behen, a Research Assistant at the same institution. It was published by Pursuit.

Dr Rachel Carey is a Lecturer in Food Systems in the School of Agriculture and Food at the University of Melbourne, where her teaching and research focuses particularly on the governance of sustainable food systems.

Rachel leads the Foodprint Melbourne project,