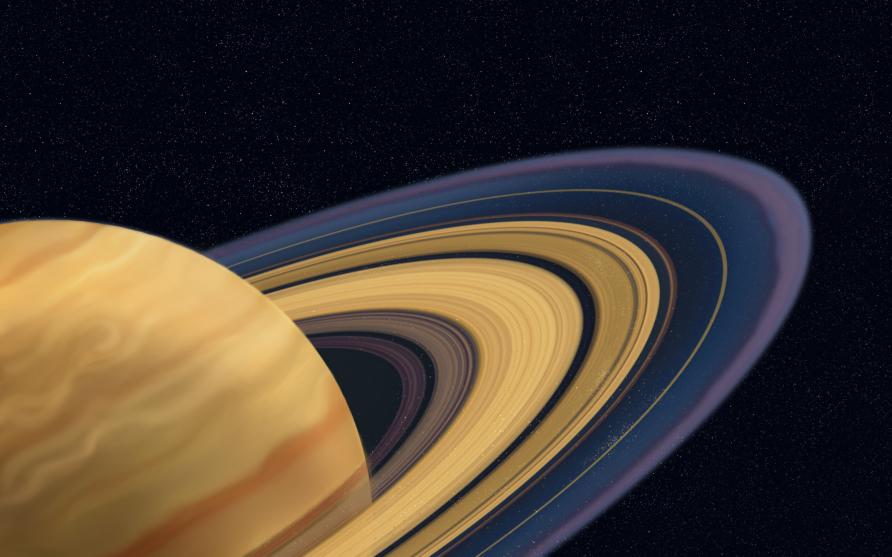

The music of the spheres

Well, the more prosaically-minded amongst you will already be a step or two ahead of me here: “Space”, your inner voice will be screaming, “is a near-complete vacuum. There isn’t any sound in space.”

And, of course, you’d be right.

Optical telescopes let us peer into the murky depths of the night sky.

Ridley Scott’s movie tagline remains as resolutely true today as it did forty years ago when Sigourney Weaver realised too late into the Nostromo’s voyage that in space no-one can hear you scream.

But if I might leap from a dystopian future to a dysfunctional Shakespearean past, there are yet more sounds in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

To leave our answer hanging unimaginatively like that, shrouded in deafening silence, feels a bit like standing in the middle of the Goolengook and missing the forest for all the trees that are in the way.

One of the most wonderful things about humankind is our collective creativity.

We have never let the limited capacity of our senses constrain our ambition to reach beyond them.

Optical telescopes let us peer into the murky depths of the night sky and resolve detail far finer than would ever be possible with the naked eye; radio telescopes show us the vibrant colours of the cosmos that lie beyond the narrow confines of the visible spectrum, and, at the opposite end of the scale, scanning tunnelling microscopes reveal the intricacy of matter at an atomic level.

Telescopy and microscopy have extended our sense of vision almost to the very limits of possibility.

But consider those microscopes: they don’t ‘see’ in the traditional sense.

We can listen to space using spacecraft-mounted probes and sensors as hearing aids.

They work by passing a very fine electrical probe over the surface of a specimen, effectively ‘feeling’ their way and generating structural information that allows us to piece together a three-dimensional image of the material.

It’s a process known as visualisation — converting data from an abstract form into a more concrete pictorial representation — and thanks to the ubiquity of personal computing it’s so commonplace that often we don’t give it a second thought.

If you’ve ever used sound-editing software, for example, you’ll be accustomed to working with audio using a time-domain display that visualises the compressions and rarefactions of the underlying sound wave as a series of undulating lines onscreen.

It’s not really what a sound wave looks like, but then when was the last time you caught sight of a longitudinal sound wave in the wild?

So, if we can visualise sound, why not the same thing in reverse?

Sonification is the process of taking data — any sort of data — and turning it into sound in a way that helps to perceptualise the underlying phenomena.

Consider the immediacy with which the ticking of a Geiger counter conveys information about radiation levels; there is a physicality that you just don’t get from a visual display.

Our hearing has evolved to be exceptionally sensitive to minute and anomalous changes to our auditory environment; just think of the way you can stand in the middle of a busy city and be completely oblivious to the thrum of metropolitan life until the sudden honk of a car horn alerts you to the fact that you’re about to step into oncoming traffic.

Radio telescopes show us the vibrant colours of the cosmos.

If we really listen to the thrum of the cosmos using spacecraft-mounted probes and sensors as hearing aids, we get a completely different perspective on the celestial phenomena that surround us.

By examining data gathered from NASA’s Themis mission, for example, a team from Queen Mary University in London discovered that the magnetopause, part of the Earth’s magnetic shield, resonates like a drum skin.

It’s a finding that really comes to life when you hear it beating.

Lead researcher and space physicist, Dr Martin Archer, says: “Earth’s magnetic field is a gigantic musical instrument whose symphony affects us greatly through space weather. We’ve known analogues to wind and string instruments occur within it for decades, but now we can add some percussion into the mix too.”

That idea, that the Earth is like a giant percussion instrument is an interesting one.

It uses poetic metaphor to tie the phenomenon to our lived experience so that we might understand it better, and of course we can use sonic analogues and metaphors in exactly the same way.

Following a Coronal Mass Ejection event, the solar wind rains a torrential downpour of charged particles on the umbrella of the Earth’s magnetosphere. What would help to convey that idea better? The ethereal wail and whistle of the radio waves that result, or the sound of a sudden rainstorm?

The magnetopause, part of the Earth’s magnetic shield, resonates like a drum skin.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of the Moon landings, NASA and the European Space Agency has released an interactive, remixed collection of the sounds of space called Space is the Place.

And we can take that idea further still.

Whether it’s Holst’s Planets or David Bowie’s Space Oddity, musical representations of space might not convey much specific detail about the structure of the cosmos, but they do tell us something interesting about how we conceive of it and our place within it.

So, let’s come back to my original question.

What does space sound like? Well, if I might misquote Shakespeare one more time, it’s full of sound and fury, and it signifies more than you might imagine.

Give it a listen.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Professor Kenny McAlpine is the New Melbourne Enterprise Fellow in Interactive Composition at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music.