Prospects for PNG

2023 signified recognition of Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) growing geostrategic importance in the region. PNG signed a Defence Cooperation Agreement with the United States and a security agreement with Australia, to counter China’s growing military presence in the Pacific. PNG also hosted other foreign leaders from Australia, India, France, Indonesia and Hungary — discussing issues ranging from environmental conservation to boosting trade and education assistance.

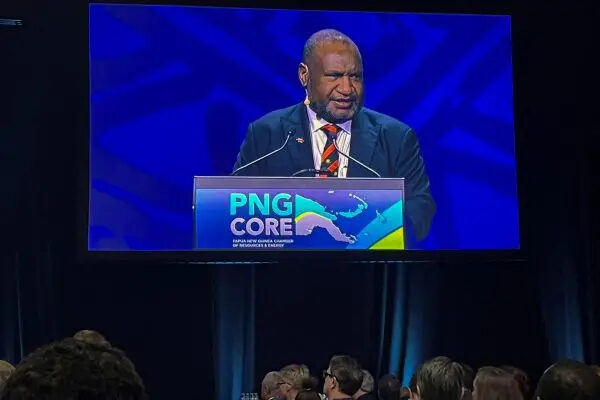

Political stability at home has allowed PNG to further its interests internationally. This will end in February 2024 when the grace period — an 18-month period following the country’s elections which bars votes of no confidence — expires. At present, no obvious candidate has emerged to replace Prime Minister James Marape.

Marape’s dominant coalition government holds 103 seats in the 118-seat parliament. With 53 members of parliament from his political party, PANGU, Marape wields considerable influence over legislature and policy. But Marape’s position is not immune to leadership challenges both from inside and outside his coalition.

The economy is performing strongly. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that real GDP grew by three per cent in 2023 and will grow by five per cent in 2024. But high growth in 2024 depends on new resource projects. Schedules for many of these projects remain uncertain. The investment phase of the US$10 billion Papua Liquefied Natural Gas project planned for 2024 has not been confirmed. While the Porgera gold mine has reopened slowly after being closed for over three years, progress toward establishing the Wafi-Golpu gold mines has stalled.

Given the enclave nature of the resource sector, non-resource GDP provides a more accurate picture of the economy. Real non-resource GDP is expected to grow by 4.6 per cent both in 2023 and 2024, according to the IMF. Between 2010–2020, real non-resource GDP growth averaged 1.3 per cent. This has been lower than the government’s official population growth rate of 3.1 per cent, leading to a decline in per capita incomes and average living standards. Only sustained real non-resource GDP growth above population growth can arrest the decline in living standards.

Economic growth has also not translated into job growth. Formal employment — representing roughly a tenth of PNG’s workforce — contracted in 2023. Job losses in construction and manufacturing have driven the contraction.

Meanwhile, the government’s 2024 budget reveals higher revenue and spending targets. Government revenue is projected to increase by 14.7 per cent in 2024, driven by a large increase in income, profit and capital gains taxes. Planned spending of almost 27.4 billion kina (US$7.4 billion) is also up by 8 per cent from 2023.

The lower growth in spending compared to revenue means the fiscal deficit has shrunk by 1 billion kina to 4 billion kina (US$1 billion). The deficit is consistent with the government’s plan to reach a fiscal balance in 2027. While this is a positive development, recent experiences of unmet revenue targets and cost overruns means put PNG’s 2024 budget estimates at risk.

Reducing the fiscal deficit is positive as it will ease PNG’s debt profile. PNG’s debt currently stands at 52.8 per cent of GDP. Marape’s shift to deficits has lowered interest rates on domestic government securities as demand has fallen. Despite cheaper debt, the IMF classified PNG as at high risk of debt distress. State-owned entity debt is particularly concerning, amounting to under 7 per cent of GDP. Combined with public debt, it breaches PNG’s legislated debt limit of 60 per cent.

Since 2019, Marape’s administration has deepened its engagement with the IMF — unlike previous governments. Engagement with the IMF has enabled Australia to overtake China as PNG’s largest bilateral creditor by providing budget support since 2019. Where China is less flexible on repayments during hard times, Australia is the preferred lender given its large development focus in PNG.

The loan program has allowed the IMF to introduce important reforms. One reform has been to require a roadmap to move to a market-determined exchange rate. The reform has devalued the PNG kina. But the nominal exchange rate has not fallen enough to cause the real exchange rate to adjust to its true value.

Since 2014, PNG has operated a de facto crawling pegged exchange rate. The exchange rate regime requires the country’s central bank — the Bank of PNG (BPNG) — to ration the availability of foreign exchange (forex). Forex shortage has become a major headwind for business, recently affecting the imports of petrol, diesel and aviation fuel, resulting in fuel shortages and the suspension of domestic flights. BPNG will need to raise its monthly forex issue above the current limit of US$100 million to address the backlog of forex orders valued as high as US$1.2 billion.

PNG’s economy has rebounded since the COVID-19 pandemic. Economic growth and political stability have allowed PNG to host important foreign leaders, reduce the fiscal deficit and introduce exchange rate reforms. While this progress has been positive, PNG enters a period of political uncertainty that puts all these gains at risk.

This article was published by the East Asia Forum.

Maholopa Laveil is an Economics Lecturer at the University of Papua New Guinea. His research interests include fiscal and monetary policy in Papua New Guinea, and election and parliamentary politics, tariff policy and economic history in that country.