The mystery and the legacy of Australia’s immigrant selectors

The selection period of Australian history was short. The “Selectors” were those who took out licences to farm small holdings in response to the Land Acts of 1860s that allowed freehold occupation of up to 320 acres.

It took only the last four or so decades of the 19th Century for much of rural Australia with agricultural potential to be transformed to freehold commercial farming. It was the revolution we think we never had. Selection transformed the colonies economically and also gave us an image of ourselves that we still continue to laud. Unfortunately we appear to have filed this story away as a piece of unimportant history.

The selection period sits within a framework of worldwide dislocation not unlike that which we are currently experiencing. During the first half of the 19th Century, the British Isles experienced a great upheaval to traditional rural or peasant life. There were the Enclosures in England, the Clearances in Scotland and over population and the Great Hunger in Ireland.

Some of these dislocated people chose not to drift into the overcrowded industrialising cities but rather to seize an opportunity to immigrate to the New World. Australia, Canada, the United States, South America and Africa represented opportunities to achieve a better rural life. My great grandparents were amongst these opportunists.

In Australia, as the dust settled on the gold rushes of the 1850s, the clamour for land for farming rose to a point of political potency. The squatters had come to dominate the vast inland plains. They leased hundreds of thousands of acres to graze sheep and cattle.

Increasingly this was seen as not meeting the needs of the growing population. Political power was shifting to an alliance of miners and business that sought more intensive development of the land. This alliance was to overcome the squatter dominance and initiate the selection period of the second half of the 19th Century.

In a piece of parallel history, a similar political tussle was being acted out in the United States. The Homestead Act of 1862 led to the “opening up” of great swathes of the American West to smallholder farming.

In his book The Victorians, Settling (1984) Tony Dingle describes the beginning of the selection era in Victoria:

In August 1860 Parliament House in Melbourne was mobbed by a large crowd demanding “A Vote, a Rifle and a Farm”. Most of the demonstrators already had the vote and many probably owned a rifle. What they really wanted was to own land and settle down as yeoman farmers. The attempt to create a class of yeoman farmers profoundly influenced the development of Victoria for almost a century.

This agrarian movement concept as espoused by Chartists and others was initially implemented in the “systematic colonisation” of South Australia in the 1840s. However, Dingle points out that selection never met this yeoman self-sufficient peasantry objective. From the very beginning selection equated to commercial viability.

In Victoria, a total of four Selection Acts were passed – 1860, 1861, 1865 and 1869 – which progressively diminished squatter rights and increased the chances of those of lesser means to acquire and to farm up to 320-acre smallholdings. Most of the Australian states went through this process but in Victoria the move to selection and against squatter dominance was particularly strong. We must thank the miners for this.

Once the legislative conditions were favourably established for freehold land selection, a great land rush occurred. This resulted in Australia being rapidly transformed from the landscape that the Aborigines had managed for thousands of years to the farming landscape we know today.

Success or failure in selection was dependent on both individual selector awareness and capability and on the climate, soils and vegetation of where they selected. This might have been beyond the Great Dividing Range on the vast inland wooded grassy plains or in the higher rainfall heavily forested coastal areas in climates that ranged from cool-temperate to sub-tropical and tropical. Hence, there are many stories to tell and through such stories we might understand both the mystery and the legacy of the selectors.

The O’Kane Story

My story is that of my paternal great-grandparents Maurice O’Keane, (O’Kane) and Anne (Annie) Whyte. They were selectors in Southern New South Wales and Northern Victoria who grew wheat.

Maurice and Annie were natives of Ireland. Maurice was born in 1836, the eldest of eight children. According to evidence collected in Ireland by family historian Frances Hale, his parents, Michael and Deborah were comparatively well off tenant farmers living 30 kilometres south east of Limerick City and close to the border with Tipperary. Annie was born around 1845 and hailed from County Leitrim, one of the poorest and most rural counties of the whole of Ireland.

Maurice spent some time in a seminary but eventually left. No doubt his parents would have wondered what next for Maurice. Our family history is unclear about why Maurice left Ireland and anecdotes abound. However, the most plausible explanation is that there was no place for him back on the farm as there were too many other mouths to feed.

For a young Irish person in the 19th Century the only available opportunity was emigration. The Penal Laws of the 18th Century severely restricted the majority Catholic population. They could not hold any office of state, stand for Parliament, vote, join the army, practice at the bar or buy land.

The Protestant Ascendancy, an elite of English origin, came to own most of the land. The great mass of people became tenant farmers. Agitation by Daniel O’Connell and later Charles Stuart Parnell culminated in the Land Bill legislation of 1881 and the re-enfranchisement of Catholics. This experience gave Irish emigrants a particular obsession to own their own land.

On 22 September 1864, Maurice left Liverpool on the ‘Red Jacket’ to arrive in Melbourne on 21 December 1864. He was an unassisted immigrant. His parents probably paid for his ticket of passage.

On arrival in Melbourne, Maurice went directly to Pyalong where his uncle Patrick Cooke lived. Here, amongst the large Irish community of Kilmore/Pyalong, he met Annie Whyte. In 1868, they married in Belfast (now Port Fairy) where Annie’s sister Fanny and her husband James Gallaher were hoteliers.

After marrying, Maurice and Annie remained in Pyalong where they ran a small rural school for a while and then they tried potato farming. After some years they decided to go north and select land. We don’t know what drove this decision but again we have a family anecdote. This is that Annie had told Maurice on his proposal that she would not marry a teacher. Her proposition was that they would be farmers. And so it was to be.

In 1874, the family set out for Jerilderie in what is described in our family history as a “covered cart” drawn by horses or oxen. By this time there were already four children – Michael (Mick), Patrick (PA), Ann and Edward (Ned). Ned was barely one year old.

The choice of Jerilderie was a bad one. Their first crop failed and they decided to “walk off” the selection. In Jerilderie today, some 150 years later, there is a paddock called “O’Kane’s” that has not seen a crop on it ever since or so I am told!

Maurice and Annie were undeterred. They tried again, this time back in Victoria at Terrick Terrick East near Echuca. Here, in 1876 after waiting nearly one year they were successful in selecting 311 acres that had been already “forfeited”.

Added to the farming disappointments there was personal tragedy. Timothy, born in 1875, lived only nine months and died of bronchitis. A second Timothy was born in 1876. One Timothy replaced another! Three more children were born at Terrick Terrick East – Margaret in 1878, Deborah in 1881 and Ellen in 1883.

In late 1884, Maurice and Annie moved again. This time it was to Boosey some 140 kilometres to the east. Again, it is not clear why they left Terrick Terrick East. At Boosey they took over another forfeited selection of 312 acres.

On to Boosey

Boosey was much more to their liking. As time went on they acquired more blocks. The family also continued to grow with two more children born at Boosey – Maurice and William (Bill). Maurice was my grandfather.

The last years of the 19th Century and the early years of the 20th Century saw three premature deaths and the death of the patriarch. Deborah died in 1892 of rheumatic fever. She was just 11. Ellen was only 21 when she died in 1904. Margaret (Madge), newly married, died at 28 in childbirth with the child also dying. Maurice died in 1900 aged 64 of, I understand, Bright’s disease.

If tombstones can measure achievement, the O’Kane family gravestone in Yarrawonga cemetery tells us that the family was successful. It is a fine monument but it is also etched with the sorrow of those three young women who died before their time.

This is the brief chronicle of my family’s selection experience. It has a biblical character about it in terms of it being a wandering journey to find the Promised Land!

Our family story though is missing explanation of how Maurice and Annie dealt with the challenges, the disappointments and the achievements of selection. I marvel at this intrepid couple yet feel their story is underexposed.

Mainly on the basis of family anecdotes, I proffer that of the two, Annie was the more forceful and more driven to succeed. Annie was married at 23 and was either pregnant and/or breast-feeding a baby for the next 22 years or so. She had her final baby at the age of 44. Historians have assessed that success in selection was, to a large degree attributable to the wife and mother. By all accounts, Annie was pivotal to their perseverance and ultimate success as selectors.

Historians Tony Dingle and Charles Fahey, in his book John Sweeney and the Making of an Australian Farming Landscape (2011), have studied Victorian selection in depth and provide some answers to my ponderings. They have written in detail about the difficulties of living the selection life, the role of the family, the attitude to education, the commercial imperative, farmer adaptation and mechanisation, access to markets, aggregation and transition to sustainable modern agriculture.

Eventually the battles with nature and the elements were largely won and land values increased accordingly as grain harvests increased to a point that Australia became a premier supplier of wheat and other grains to the world. Both Dingle and Fahey highlight that selection created opportunities and a progression to a better life for many if not always through direct farm success. Failure according to these historians meant other opportunities rather than disaster. Dingle argues that:

“Selectors saw land not as a legacy to be safeguarded but an investment to be exploited.”

The selection era came to an end as the 19th Century closed. For the first half of the 20th Century we remembered it but since then it has ebbed from our memories. We should remember the selection era, warts and all, because, as with all our stories, there are good bits and bad bits but most importantly there are lessons.

Remembering the Selection

There are three principal reasons why we should remember the selection era.

Firstly, the selectors laid the foundation for agriculture to grow into the significant and sustainable economic sector that it is today.

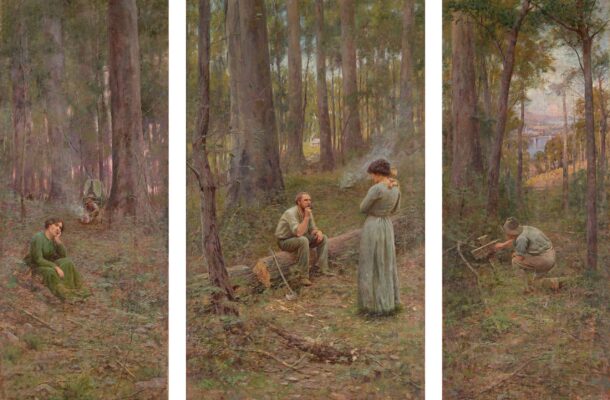

Secondly, the selectors contributed significantly to our ethos – reality or myth take your pick – of a unique laconic, free thinking, self-reliant and self-deprecating character. Frederick McCubbin’s famous painting The Pioneer (1904 ) headlines this article and, in the words of contemporary commentator George Megalogenis in Australia’s Second Chance (2017), encapsulates Australian character as the “Australian duality”:

“We are a seemingly confident but ultimately anxious people.”

It is optimism duelling with self-doubt. Yes, seemingly contradictory but logical given the highs and lows of life on a selection. Both the pathos and the ironic humour that were needed to cope with all the difficulties are there in the poetry of Lawson, Patterson and O’Brien and in the prose of Steele Rudd. We see only pathos in McCubbin’s painting, “The Pioneer.””

Finally, it is also important that we recognise what selection prevented. If the squatters had got their way the legacy would be more akin to class stratified England or European elite dominated South America.

I have used the experiences of my great-grandparents as the backdrop for this tale of selection. They were Irish Catholics but the experiences were similar for the English Methodists, the Scots Presbyterians and the German Lutherans who all selected in the second half of the 19th Century.

The world and Australia has changed greatly since these intrepid immigrants set out to create a future out of the wilderness. It is difficult to even visualise the selector circumstances from our contemporary and cossetted perspective.

Annie died in 1917. By then she had 23 grandchildren with another 17 to come! The family, which began in a fiercely proud rural-Irish cocoon, has expanded beyond imagination to number some hundreds. Very few of us now earn our living from the land and we have moved as Australia has moved. Mostly we live in large cities.

Our clan can now claim inheritance from many other places beyond that small and green land at the western edge of Europe. My grandson, for example, can trace his origins, not only to Ireland, but also to China, Sicily, Cornwell and England. I believe Maurice and Annie would be pleased with that.

So should we all. So, let us celebrate our selector heritage.

Read the companion article to this piece “The Hardscrabble Lives of the Selectors”.

Bernie O’Kane has a background in urban infrastructure investigation, planning, design and construction. He has worked in both the public and private sectors in Australia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam, and has a Masters in environmental planning and water resources from Stanford University.