A new tool to tackle seafood fraud

Warming waters due to climate change, pollution, overfishing and fraud in the seafood supply chain means that knowing where your seafood comes from, and that it has been sourced sustainably and without forced labor, is as important as ever.

While Australia has the third-largest fishing zone in the world, covering more than 8 million square kilometres, it is estimated that over 60 per cent of seafood consumed in Australia is imported.

Researchers at UNSW Sydney are part of an ongoing collaborative project led by Australia’s Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) to develop new ways to determine where seafood has been sourced, and whether it has been farmed or wild-caught.

“The seafood supply chain, especially with seafood imported from across the globe, is quite long. And there are various people at different points in the supply chain that handle a seafood product,” says Associate Professor Jes Sammut from the School of BEES. “And in that process, there is the risk of what we call ‘food fraud’.”

Mislabelling is a common type of food fraud. “For example, a product may say that it’s a barramundi fillet from Australia, when it’s really a barramundi fillet from overseas. Mislabelling can also happen at the retail end, so a cheaper product can be labelled as more expensive based on its origin and production method,” says A/Prof. Sammut.

Looking for solutions to these ongoing challenges, ANSTO scientists, led by Dr Debashish Mazumder, and a research team at UNSW have developed protocols and mathematical models for a handheld device that can determine the origin of seafood by providing a unique profile of its elements.

“The idea is to use the handheld device at any point in the supply chain, providing details that can lead to a more sustainable and ethical seafood trade,” says A/Prof. Sammut.

This ongoing research is part of a collaborative effort between ANSTO, UNSW, Sydney Fish Market, Macquarie University and the National Measurement Institute.

“We have had a very productive research partnership with ANSTO. Working with the project lead, Dr Mazumder, the wider team at ANSTO and our partner agencies has created opportunities to translate this research into impactful outcomes,” says A/Prof. Sammut.

“This device is really about empowering the consumer, empowering the retailer and also empowering the wholesalers to know more about the produce they’re buying and selling.”

A unique ‘elemental fingerprint’

As well as food fraud, escalating environmental and human rights threats and financial challenges in the food industry mean that being able to determine the origin of food – also known as food provenance – is becoming increasingly important.

“Historically, people used DNA to help confirm what species a fish is,” says A/Prof. Sammut. “But it doesn’t tell you where it came from or whether it was farmed or wild.”

As A/Prof. Sammut explains, scientists have used high-end equipment – such as X-ray fluorescence and isotope ratio mass spectrometry – to determine food provenance in the lab by studying the elemental profile of seafood. “For example, by measuring the abundance of different metals and determining the different ratios of stable isotopes in a sample, we can create a unique chemical fingerprint.”

Importantly, the elements and isotopes found within any individual organism are specific to each organism and determined by factors including diet, climate and environmental conditions.

By measuring these elements and isotopes, scientists can record a unique “fingerprint” that varies by geographical location or production method.

Developing a handheld device

While elemental profiling has emerged as a useful tool for authenticating provenance, its adoption by the food industry has been slow, as most of the equipment remains lab-based.

Dr Mazumder, who is also an adjunct Professor in UNSW’s Centre for Ecosystem Science, worked previously with A/Prof. Jes Sammut on improving fish feeds in aquaculture. “This unique university and industry collaboration extended to the seafood provenance research. Initially, the research team used a range of nuclear analysis techniques to determine seafood provenance,” says Dr Mazumder. “The outcome of this work helped the team theorise that a portable device could be used to determine the provenance of the seafood we eat.”

The team repurposed handheld elemental scanners (such as the Olympus Vanta device), typically used to scan sediment samples, to scan biological tissue to obtain the elemental fingerprints of various seafood products.

“So while the instrument itself isn’t new, the repurposing of it for seafood is, as well as all the work testing and developing the protocols,” says A/Prof. Sammut.

Dr Debashish Mazumder holds the Olympus FXS handheld scanner, provided by Olympus.

Over the last five years, the team has produced a number of papers testing the proof-of-concept of the lab-based itrax and the handheld scanning device for the provenance of a variety of seafood.

In a recent study published in Food Control, the multidisciplinary team used the handheld X-ray device to locate the site of origin of black tiger prawns from across Australia, with over 80 per cent accuracy.

“This paper brings us a step closer to seeing the scanner device being used on the fish-market floor, to determine in real time, where seafood has come from, and how it was produced,” says A/Prof. Sammut.

Knowing where your food comes from

While the seafood industry in Australia has an international reputation as a trusted supplier, the long and opaque supply chains in the global industry make it particularly vulnerable to food fraud.

Last year the Australian government promised $1.6 million to deliver on its commitment to introduce country-of-origin labelling in the seafood industry. The government hopes to work closely with the seafood and hospitality sectors to improve seafood labelling and help consumers make informed decisions about the food they buy.

But until now, there has not been a single method that can easily determine food origin and be used to combat seafood fraud.

“We hope this tool will help advance the country-of-origin labelling, and if that means your local fish and chip shop will need to state the geographical origin of a product, including whether it was farmed or wild. So again, this tool is a way of ensuring this compliance,” says A/Prof Sammut.

“Technological innovations such as this scanner will play an important role in the prevention of food fraud in years to come,” says Erik Poole, Innovation and Technical Manager at Sydney Fish Market. “Most importantly, by demystifying the supply chain and providing consumers with trustworthy information about seafood provenance, we hope that research like this equips Australians with the tools to confidently choose Australian seafood, whenever possible.”

Food fraud isn’t the only thing the handheld device can help combat. Knowing where a product has come from can also help identify seafood that may have been produced by forced labour, as well as determining locations for biosecurity breaches. The elemental profile of seafood can also assist with determining whether a product reaches food safety standards.

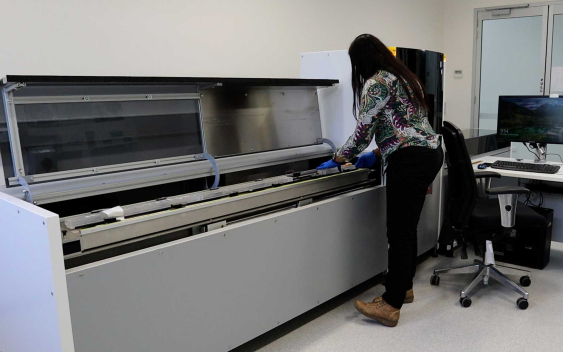

Patricia Gadd, part of the collaborative team, handles an organic sample using the full-sized itrax scanner in the lab.

Expanding the database

While the use of the handheld scanner has huge implications across the seafood supply chain, there are steps that need to be taken before we can expect to see it in regular use.

“We need the industry to tell us which products they’re most concerned about,” says Dr Mazumder. “We know the source of prawns and barramundi are issues, but what else?”

This is where the partnership with Sydney Fish Market is so essential. “We need to get samples across Australia and overseas, to get the information into our database, so that when you analyse seafood using the handheld scanner, it can tell you with more precision where the product has come from,” says A/Prof. Jes Sammut.

The provenance technology has been developed over a number of years with the help of research. “At the moment, we can comfortably say whether a tiger prawn is wild-caught or farmed, and we are now at a point where there is an opportunity for expansion,” says Dr Mazumder.

This research also involved Patricia Gadd, Dr Jasmin Martino, Dr Karthik Gopi, Dr Jagoda Crawford, Dr Carol Tadros, Prof Neil Saintilan and Nondita Malo from across the ANSTO and UNSW Sydney partnership.

Lilly Matson is a News and Content Coordinator at the University of New South Wales.