Climate change and the precautionary principle

The first United Nations Climate Change Conference (Conference of Parties — COP) was held in Berlin in 1995. Since then there have been 26 more COPs. That is 27 years of high-level discussion on what to do about climate change and we are not there yet.

Whilst there has been significant progress in the last few years, there remains more promising than actual achievement. Current climate modelling projections show that existing pledges, commitments and action are not sufficient to contain Global warming to less than 1.50C.

Even with the growing awareness the proposed more stringent action may not be enough to save us from catastrophe. There remains amongst both political leaders and societies worldwide a sense that this crisis can be muddled through.

A lack of urgency

Why are we all so relaxed? Why is there no sense of urgency?

Engineers have, for centuries designed buildings, bridges, roads, reservoirs and other infrastructure with a factor of safety. This means they add extra strength or capacity greater than what they estimate is needed. Hence a typical engineering design is not a best estimate but rather a conservative provision of what is required.

This is done to protect the infrastructure against uncertainty of unforeseen causes of failure of the infrastructure. This is also referred to as the precautionary approach. It is a sound practice because, for the sake of a few extra rivets, beams or columns, so to speak, the benefit of avoiding failure is well worthwhile.

The world has not taken this precautionary path with climate change. In fact the opposite is happening. It has been more of a wait-and-see approach or it just 27 years of talking.

Over the recent decades, the climate scientists have continually refined their estimates of climate change trends. In doing so the climate scientists are determining best estimates of atmospheric temperature and other climatic variation attributable to climate change. These estimates do not include a precautionary provision.

In one respect this emphasis on rigour and accuracy is in response to the attacks by climate change deniers on the credibility of the science of climate change. It is quite bizarre that society has allowed the climate deniers to control the debate. Imagine if we allowed a denier to question the use of a factor of safety in a bridge design.

The irony of this is that, whilst accuracy of estimation is important it is the recognition of uncertainty that provides the confidence that ‘failure’ will not occur. Hence, defensible estimation and realistic appreciation of the limits of this estimation are equally as important for a satisfactory outcome.

Climate Modelling

What then are the uncertainties that are not being accounted for in the climate modelling?

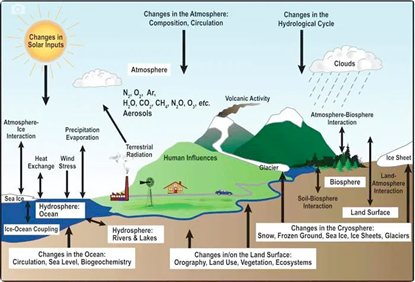

Firstly, there is the uncertainty of climate modelling itself. The climate scientists use mathematical models to predict temperature change and other effects on world climate due to global warming. These climate models are representations of what is a very complex set of meteorological, oceanographic, biological and hydrological interactions. They are, without apology, simplifications of these complex interactions and therefore there is inherent uncertainty in the model estimates.

Furthermore because they are predictive tools they are operating beyond their calibration range. Mathematical models of natural systems are most reliable as tools of comparison rather than for providing absolute estimates. This is why the climate models are most useful in comparing scenarios for action on climate change.

Tipping Points

The other major uncertainties relate to climate phenomena that are potentially ‘tipping points’ as a result of GHG accumulation and Global warming. These tipping points are not easily or effectively modelled.

These potential tipping points will result in irreversible economic, social or environmental impacts. The effects are often diverse and extensive. These tipping points include the slowing of the North Atlantic Gulf Stream, the thawing of the Tundra permafrost, the melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice caps, the destruction of coral reefs and desertification. There are already significant changes in our climate that may or may not be reversible. There is little certainty and plenty of anxiety.

One example of direct importance to me is the significant reduction in rainfall in South-Eastern Australia. This has occurred over the last thirty years and is a major threat to agriculture, the environment and urban living for around 60% of the population of the country.

What does the reluctance to overtly consider uncertainty mean to action on climate change? It means we dither and debate rather than react and respond.

This takes me back to the engineers and their buildings, bridges, roads and reservoirs. If we are satisfied with the precautionary principle for the design of such infrastructure to reduce the risk of its failure, surely we can do the same to protect against failure of the world’s climate?

Political Leadership

The answer to this question lies in the motivation of our political leadership. The sad truth is that our politicians are more attune to short-term risks, particularly the risk of not being re-elected, than they are to providing vision and policy for a better society over the longer term. As has been manifest in recent decades the result is that the risk of future catastrophe is downplayed and even denied.

In general, nations have been slow to act and what should have happened two decades ago, if the precautionary approach had been adopted, is only now becoming an imperative. Australia is a particularly guilty of this reluctance to act. The obvious motive is protection of the massive coal industry, which is the country’s second biggest export. For almost two decades, we have witnessed the climate wars during which climate deniers initially attacked policy that was effective in reducing GHG emissions and then, on obtaining control of the government, they dismantled that policy.

Of course not all nations and politicians are so narrow in their visions of the future and may force recalcitrant countries, via threats of punitive action, to make stronger commitments to reducing GHG emissions. We can only hope for this.

Perhaps we should have learnt from the engineers and responded earlier. For climate change the effective factor of safety is immediate response to the recognised threat. However now it may be too late and our long delayed ‘bridge’ to containing climate change may be being built without a factor of safety.

Bernie O’Kane has a background in urban infrastructure investigation, planning, design and construction. He has worked in both the public and private sectors in Australia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam, and has a Masters in environmental planning and water resources from Stanford University.