It’s more than the money

As part of the budget, the Australian government has announced $A65 million in additional payments to GPs in rural areas. The more ‘rural’ the area, the more money GPs are paid.

But will this contribute to attracting and retaining GPs in these areas?

The Budget’s aim is to attract more GPs to rural areas, help existing GPs stay longer, and increase bulk billing rates.

The plan will provide additional payments to GPs if they bulk bill, and so provide stronger incentives to bulk-bill more services.

Overall, the aim is to attract more GPs to rural areas, help existing GPs stay longer and increase access for patients by increasing bulk billing rates.

The basic Medicare rebate for a bulk billed consultation is $A38.75. GPs already get bulk billing incentives if they bulk bill under 16 year olds and Commonwealth concession card holders. Currently, GPs in metropolitan areas get a bulk billing incentive of $A6.50, and GPs in all rural areas get $A9.80.

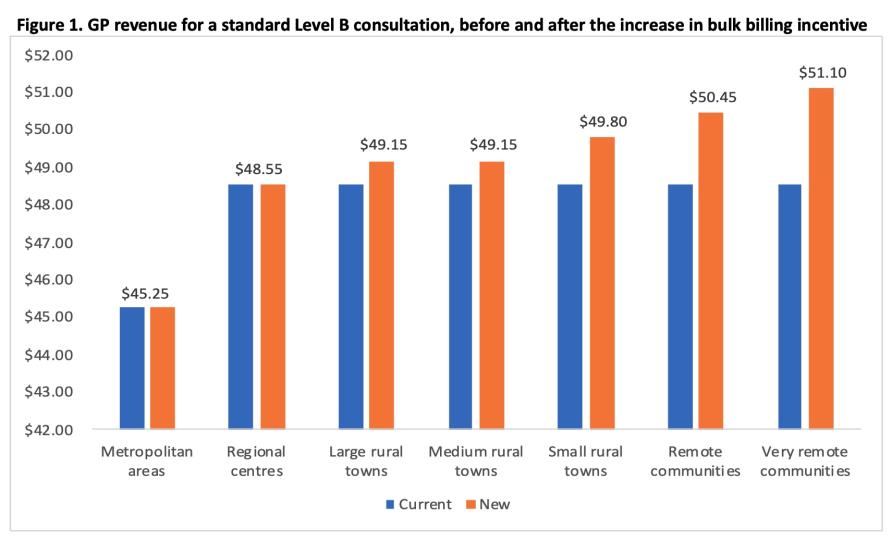

The new funding will increase these payments depending on how ‘rural’ the area is, with GPs in very remote areas getting $A12.35 compared to the current $A9.80 – an additional $A2.60.

A GP’s revenue per consultation will increase from $A48.55 to $A51.20 (up by 5.3 per cent) in very remote areas.

Figure 1 above shows the impact on a GP’s revenue for a standard 15-minute (or Level B) GP consultation that’s bulk billed for an under 16 year old or a concession card holder. A GP’s revenue per consultation will increase from $A48.55 to $A51.20 (up by 5.3 per cent) in very remote areas.

Does this matter to GPs?

Though GPs will welcome this increase in income, especially after the Medicare Fee Freeze, it’s still unclear what this all means for the typical GP.

This is important to understand, especially if the policy is to work as intended – that is, attracting new GPs to rural areas, ensuring those already there don’t leave, and increasing bulk billing.

In order to get that big picture, GPs need to know how much the total revenue for an average GP would increase in each of these areas compared to their current revenue.

No modelling has yet been released to show how total revenue would change, but it will depend on a complex mix of the number of 16 year-olds and concession card holders seen by the average GP, the proportion they currently bulk bill, whether any additional services are bulk billed as a result of the change, and the mix of different types of consultation.

A key issue here is that these incentives apply only to these specific population groups and no other patients. But these groups will account for less than 50 per cent of standard GP consultations.

GPs need to know how much the total revenue for an average GP would increase compared to their current revenue.

Consultations for other patients just receive the basic $A38.75 even if in a very remote area.

So, the impact on total GP revenue is unclear, and it’s also unclear if this will be enough to encourage GPs to move and/or stay rural.

Will financial incentives increase recruitment and retention in rural areas?

There are already a range of policies to encourage GPs to go rural, including financial incentives under the Practice Incentive Program and the Workforce Incentive Scheme for GPs who newly move to rural areas and other health professionals employed in the practice.

Our previous research using data from the Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment and Life (MABEL) survey has shown that to move a GP from the city to a rural area would take an increase in income of between 18 percent and 130 percent, depending on the rural area.

For an average GP who reported their annual income in the MABEL survey as $222,535, this means they would need to be paid between $261,700 and $511,830 to go rural.

These are very large increases and dwarf the likely to amount offered by the new bulk billing incentives. Our research also found that 65 per cent of GPs wouldn’t move no matter how much they were paid.

There are already a range of policies to encourage GPs to go rural.

We have also evaluated the impact of a change to a rural incentive scheme (what was then called the GP Rural Incentives Program) that occurred in 2010, and that affected GPs outside of metropolitan areas, but not in very remote and rural areas.

This change had no impact on the number of GPs moving to these areas, or to the rate at which GPs left these areas.

But it did have an impact on the number of GPs in training, suggesting that younger and recently qualified GPs could be more mobile and willing to move, compared to GPs who are already established in cities. It seems that these GPs should be the target of policies using financial incentives.

Where to from here?

The single most effective policy for providing access to GPs in regional, remote and rural areas has been the requirement for all doctors arriving from overseas to spend up to 10 years in a non-metropolitan area, with around 40 percent of GPs in these areas having qualified overseas.

Many other policies also exist that support the education and training of doctors outside of metropolitan areas.

While reducing reliance on overseas doctors has been an objective of government policy, at the moment it remains unclear what other policies can be used instead.

The Budget provides additional payments to GPs if they bulk bill, and so stronger incentives to bulk-bill more services.

Financial incentives might only work for younger newly qualified GPs and there is little evidence on the cost-effectiveness of other policies. So, it is likely that overseas doctors will continue to be used for the foreseeable future.

On top of this, the role of telehealth and other health professionals in rural areas also needs to be more carefully considered.

Though this budget measure puts more money in GPs’ pockets, by itself it is unlikely to help get more GPs into the bush.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Professor Anthony Scott is an Academic at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research. His research interests include financial incentives in health care and workforce and healthcare funding.