Buying friends and influencing people

China’s investment in the Pacific has redrawn the political map of the region.

Since 2008, the Chinese government has committed over USD$9 billion to infrastructure, development, education and commercial projects across Pacific Island countries, accounting for around 46 percent of total official loans provided in the region.

This number dwarfs the USD$1.35 billion loan from Japan and USD$0.93 billion loan from Australia, as the second and third biggest nation lender in the region.

This influx of Chinese capital has had a profound impact on nations such as Solomon Islands, reshaping their economic and political trajectories.

The Solomon Islands general election on April 17 will be crucial in understanding what comes next.

Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare’s close ties with China and the public view on the Chinese economic presence in the country will be tested by the opposition.

Opposition leaders including Mathew Wale under the Coalition for Accountability, Reform and Empowerment (CARE), Kenilorea Jr under Solomon Islands United Party banner, and Daniel Suidani have all openly expressed their concern about Solomon Islands’ economic dependence on China.

Sogavare’s close ties with China were first telegraphed by the withdrawal of Taiwan recognition in 2019 and reaffirmed with a security pact with China in 2022 that allows the government to request the deployment of Chinese military personnel to assist the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force.

It is easy to befriend a nation if you are building its infrastructure, sometimes for free.

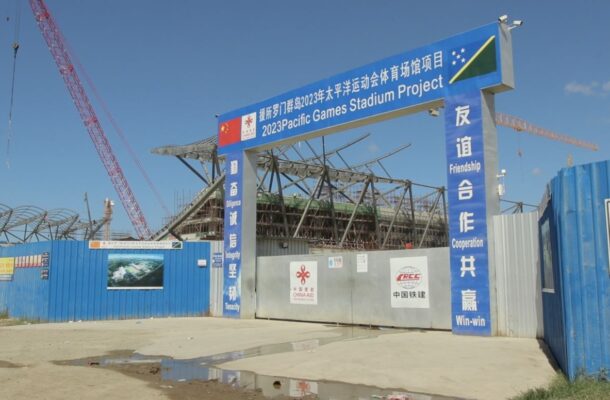

From Chinese firms developing deep water ports, to bankrolling the region’s Pacific Games which included the gift of a 10,000 seat stadium in the capital Honiara, it can pay to cosy up with Beijing.

Compare this to the aid and development programs traditionally offered by Western powers through Multinational Development Banks such as The World Bank and nations such as Japan, EU, and Australia, and China’s investment-driven approach holds strong appeal for many of these smaller countries.

A key factor is the relative lack of stringent conditions or oversight that often accompany assistance from Western sources.

While Western aid often comes with requirements around transparency, human rights, and economic reforms, China’s loans to Pacific Island nations have had no such stipulations, allowing the government greater autonomy in how funds are used.

Pacific Island nations officials prefer Chinese financing, citing the ‘fewer strings attached’ as a major draw.

This hands-off approach is enticing to leaders who may chafe at the policy prescriptions that typically come attached to Western aid.

The scale and speed of Chinese investment can also be quite alluring.

Beijing has demonstrated a willingness to rapidly deploy large sums, with the Solomon Islands receiving over USD$500 million in infrastructure loans from China during 2019-2022 to ensure its influence over that of Taiwan’s.

This contrasts sharply with the often more cautious, incremental approach of Western donors. For cash-strapped nations eager to kickstart development and modernisation, the Chinese model of state-directed investment can be a compelling alternative.

The Chinese government claims that since the 1970s, Beijing has supported more than 100 aid initiatives in the Pacific Island region, provided upwards of 200 sets of material assistance, and facilitated the training of approximately 10,000 local labourers.

However, this influx of Chinese influence also raises concerns among the international community.

There are widespread fears that over-reliance on Chinese financing is leading to unsustainable debt burdens — Solomon Islands’ debt to China is expected to grow from 4 percent of GDP in 2017 to over 15 percent in 2028.

This erosion of sovereignty is compounded by worries that China’s long-term strategic intentions may involve expanding its geopolitical reach and countering Western influence in the region.

As China’s economic statecraft evolves, it will need to grapple with growing domestic concerns about the potential risks of its overseas investment activities. China’s own economic slowdown, with GDP growth projected to fall below 5 percent this year, has heightened scrutiny of the country’s international financial commitments.

Some analysts are calling for a more cautious and selective approach to foreign investment, arguing that resources should be prioritised to address pressing domestic challenges.

Ultimately, the impact of increased Chinese investment in Solomon Islands and similar countries is a delicate balance of economic, political, and security considerations.

These smaller nations must learn to navigate this shifting landscape, weighing the benefits of Chinese capital against the potential risks and long-term implications.

A study by the Lowy Institute suggested that while Chinese-funded infrastructure projects have improved connectivity and economic opportunities in the region, they have also saddled several Pacific Island countries with unsustainable debt.

Similarly, China will need to adapt its economic statecraft to address concerns both at home and abroad, while also finding ways to maintain its influence and pursue its strategic interests in the face of intensifying great power competition.

The country’s own economic slowdown and the US-led pushback against its digital ambitions add further complexity to this challenge.

The delicate dance between economic imperatives and geopolitical ambitions will be a defining challenge for China in the years ahead, with the future of its engagement with smaller nations like Solomon Islands hanging in the balance.

The stability and prosperity of the entire Pacific region may very well depend on all the players in the region being able to strike the right balance.

The ripple effect of China’s economic statecraft in this critical part of the world will be felt far beyond the shores of these island nations.

This article was written by Teuku Riefky, a Macroeconomic and Financial Sector Researcher at the Institute of Economic and Social Research at Universitas Indonesia; and Mohamad Dian Revindo, the head of the Business Climate and Global Value Chain Research Group at the same institution. It was originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

Teuku Riefky researches macroeconomics, financial sectors, finance, fiscal and monetary policy at Universitas Indonesia. He has consulted for ADB, World Bank, UNDP, Mandiri Institute, Danareksa Research Institute, Fiscal Policy Agency and Korean Institute for Economic Policy.