More of the best science stories from 2018

Melbourne University experts share more of their picks of the best research, discoveries and big thinking from around the world in 2018.

Associate Professor Jeannie Marie Paterson, Melbourne Law School:

I’ve chosen two research success stories from 2018 that stood out as highlights for me. The research comes from two different areas of expertise – medicine and engineering – well outside my own scholarly endeavours in law.

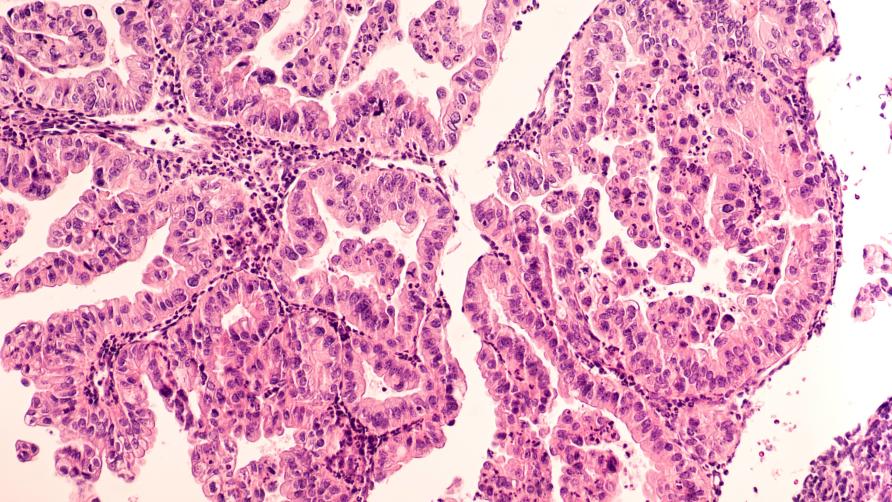

The first is research into a ovarian cancer by the team led by Professor Clare Scott, working with Dr Olga Kondrashova, at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and the University of Melbourne.

Ovarian cancer is a nasty disease. This research provides a greater understanding of why one group of treatment drugs, PARP inhibitors, are effective for some patients but not others. The goal of this and other work of the research team is the personalised treatment of patients with cancer.

Professor Scott is a personal friend. She and her team are extraordinarily hard working, tenacious and compassionate. It’s tremendous to see the commitment to this research that has such a profound impact on women’s health.

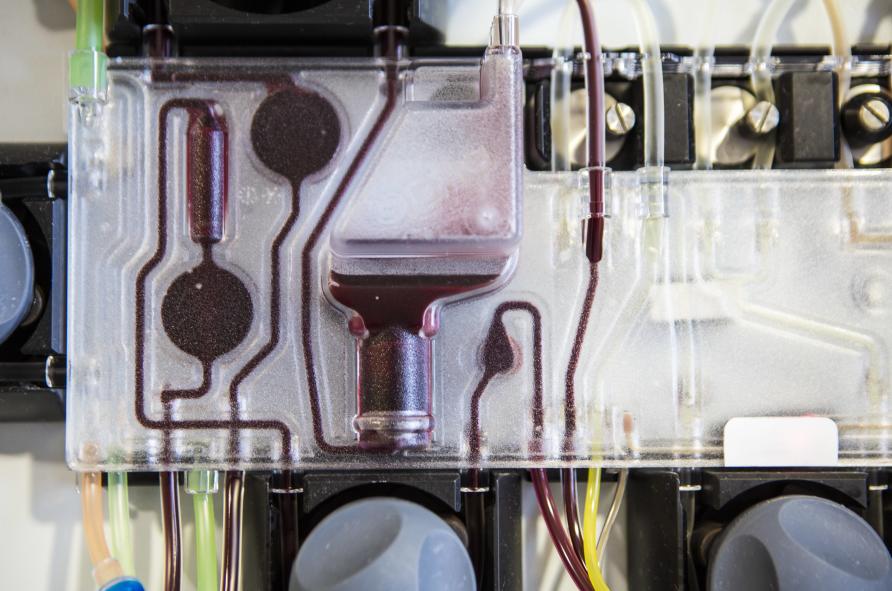

The second research advance is the use of a tiny device, the Stentrode™, which can be inserted in a blood vessel without major surgery and then used to receive and send messages to the brain.

I have been following the progress of this team led by Dr Nicholas Opie for some time via Pursuit. This combination of medicine and technology has the potential to change the prognoses for so many patients, including people with symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease or spinal cord injuries.

For me, this is more startling and fantastic than science fiction.

Professor Ian Harper, Dean Of The Melbourne Business School, And Co-dean Of The Faculty Of Business And Economics:

The Tyranny of Metrics by Professor Jerry Z. Muller from Princeton University is about what can happen when numbers replace human judgement in the management of performance. He calls this phenomenon “metric fixation”, and highlights the many ways in which it can misfire.

The most shocking example he cites is of surgeons who choose not to operate on patients with complicated circumstances in order to protect their “success” rate.

In Australia, there are many examples of metric fixation (and its associated misfires) that many of us may be able to bring to mind. Its existence in the banking industry was highlighted during the Financial Services Royal Commission. Its use in schools continues to divide opinion.

And, I suspect, its impact on politics and the media, through opinion polls, hasn’t been entirely positive.

Professor Muller’s critique of metric fixation is particularly relevant to me in my role as Dean of Melbourne Business School for several reasons. First, it’s a notable assault on what has become one of the predominant management practices of the 21st century – which is also likely to have a significant impact on students and faculty alike.

Second, it offers me insight into the way forward as a leader of an educational institution which is often judged on its metrics. For many years, Melbourne Business School has been ranked either the best, or one of the best business schools in the country by various overseas systems of measurement. It’s one of the reasons students come here.

But as Professor Muller’s book shows, focusing too heavily on measurements at the expense of human judgement can eventually have a distorting effect.

Part of my job is to stop and take stock, in order to make sure that at Melbourne Business School, we are teaching students to be the best leaders they can be, not just to remain the top-ranked institution.

Associate Professor Megan Munsie, Head, Education, Ethics, Law And Community Awareness Unit, Stem Cells Australia:

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is one of the most aggressive types of blood cancers that affects children and adults of all ages, and has the worst survival rates of any of the leukaemias. About 20 per cent of all leukaemias occur in children.

Recently, colleagues at the Centre for Stem Cell Systems collaborated with University of Glasgow, to comprehensively analyse the differences between the childhood and adult forms of AML. They demonstrated that the childhood form is biologically different to the adult, opening up the possibility of investigating treatment options specifically for the childhood form of the leukaemia.

This research was led by Dr Karen Keeshan from the University of Glasgow’s Institute of Cancer Sciences and published in Nature Communications. Dr Keeshan is a close collaborator of the Wells laboratory, led by Professor Christine Wells, Director of Centre for Stem Cell Systems.

My colleague Dr Jarny Choi, who led the data analysis on this project, says the team found a distinct molecular profile and potential gene targets for paediatric cells of origin.

It gives us hope that new and more specific treatments will arise to treat paediatric AML, which is currently treated with therapies developed for adults.

Dr Yvette Maker, Senior Research Associate, Melbourne Social Equity Institute:

I was impressed and excited by the VOICES project, an endeavour pairing people with disability and mental health service users from 13 countries, with scholars, activists and practitioners to record and amplify their experiences of being denied their human rights.

Worldwide, many people with disability are denied the right to make their own decisions – they can’t choose how they spend their money, who they have intimate relationships with or what medical treatment they receive. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilitiesestablishes that this is unacceptable.

The VOICES storytellers worked in partnership with a respondent to record their stories, put them in the broader social and legal context, and propose necessary reforms to law, policy and practice.

This community-engaged project was led by Professor Eilionoir Flynn from the Centre for Disability Law and Policy, at the National University of Ireland, Galway, alongside partner investigator, Dr Anna Arstein-Kerslake from the Melbourne Law School.

My other colleagues, Dr Piers Gooding from the Melbourne Social Equity Institute and Cath Roper from the Centre for Psychiatric Nursing were also participants, co-authoring a powerful paper on involuntary mental health treatment.

The project’s four guiding values – that everyone has an equal right to enjoy legal capacity; that people with disability should be supported in exercising legal capacity; respect for others’ voices and opinions; and a belief in empowering people to drive change – will be pinned above my desk in 2019.

Professor Peter Mcphee Am, Melbourne Graduate School Of Education:

Among the most significant research in humanities at present is that by University of Melbourne’s Professor Cordelia Fine, whose book, Testosterone Rex: Unmaking the Myths of our Gendered Minds,won the 2018 Royal Society Insight Investment Science Books Prize – often described as the “Booker Prize of science writing”.

The judges called it an “eye-opening, forensic look at gender stereotypes and its urgent call for change”. She also won the 2018 Edinburgh Medal, which is awarded to a person judged to have made a significant contribution to the understanding and well being of humanity, for her address “Science, Values and Gender Equality: Reflections from the Battleground”.

The significance of her work is that she has brought together expertise in psychology, endocrinology, biology, history and neuroscience to inform her philosophical logic to examine the age-old question of ‘innate’ gender differences.

As opposed to value arguments about whether there are essential, biological differences ‘hard-wired’ in men and women which determine key behaviour, Professor Fine looks at a range of hard evidence with sharp logic and intelligence.

Her unambiguous conclusion is that neither science nor logic support the popular idea of biological difference explaining sex inequality.

This is vital because we know that there are still very significant differences in life-chances, salaries and power between men and women. All too often, this is rationalised by appeals to ‘common sense’ biological explanations of sex-based inequalities.

This article was published by Pursuit.

Open Forum is a policy discussion website produced by Global Access Partners – Australia’s Institute for Active Policy. We welcome contributions and invite you to submit a blog to the editor and follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin and Mastadon.