Homelands – A personal history of Europe

The political transformations in Europe of the postwar period have been some of the world’s most profound geopolitical trends. And whatever the outcome of the Ukraine war, more dramatic changes could well be on the horizon for Europe. To gain a deep understanding and feel for the postwar history of the old continent and what might lie ahead, there may be nothing better than Timothy Garton Ash’s recent book, Homelands: A Personal History Of Europe.

Garton Ash is an “historian of the present” who has spent 50 years travelling around Europe, witnessing great events, meeting people, and studying the continent. A professor of European studies at the University of Oxford, he has authored ten books charting the transformation of Europe. He has also been able to pursue a parallel career as a journalist for the Guardian, The Independent and The Spectator.

In Garton Ash’s words, Homelands is an example of an unusual genre, “history illustrated by memoire and reportage.” But it is not the entire history of Europe over the past 50 years. Rather, it is a history of Europe and freedom, the two leitmotifs of his work.

The book is peppered with stories that illustrate larger historical points. For example, when Garton Ash met German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who had just reunited Germany, in his office in autumn 1991, Kohl said “By the way, do you realise that you are sitting opposite the direct successor to Adolf Hitler?” Garton Ash argues that this “gobsmacking” comment reflected Kohl’s great sense of history. Hitler got everything wrong as he tried to put a German roof over Europe. Thus, Kohl was determined to put a European roof over Germany.

Garton Ash’s historical narrative begins in 1972/3 with his European travels, at which time most people on the continent still lived under dictatorships. Taking into account Eastern and Southeastern Europe, as well as Spain, Portugal, and Greece, 289 million Europeans lived in democracies, whereas some 389 million lived under dictatorships. From the mid-1970s, Europe began removing the shackles of autocracy, starting with Spain, Portugal, and Greece. This was the beginning of an extraordinary 35-year upward curve in the enlargement of freedom in Europe.

At the same time, there was also an unprecedented enlargement of the “geopolitical West” through the expansion of membership of the European Community/Union and NATO. Garton Ash argues that never before had there been such progress towards a Europe “whole and free.” There were of course setbacks along the way, like the wars in Yugoslavia and 9/11. But the general European trajectory was upward.

European history would commence a downward turn in 2008, beginning with the eruption of the global financial crisis, and then Russia’s seizure of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from Georgia. Then followed a cascade of crises, with the Great Recession and the eurozone crisis.

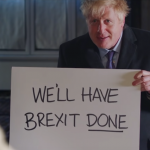

In 2010, Viktor Orbán started demolishing democracy in Hungary. In 2014, VladimirPutin seized Crimea and started the Russia/Ukrainian war in eastern Ukraine. 2015 saw the European refugee crisis, while 2016 brought Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. Since then, nationalist/populists like Germany’s AfD and France’s Rassemblement National have been doing well in elections.

The Covid-19 pandemic shook Europe badly. And then on 24 February 2022 came the biggest crisis of all, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which started Europe’s largest war since 1945. This marks the end of Europe’s “post-wall” period, which lasted from 9 November 1989 to 24 February 2022.

What provoked these crises? Garton Ash offers three possible explanations. First, he believes that Europe and the West naively assumed that the positive trends (until 2008) would continue, even though the fall of the Berlin Wall was the most non-linear event in European history – this is the fallacy of extrapolation. Second, he argues that Europe and the US suffered from multiple variants of hubris.

But Garton Ash argues that most important was the failure to learn the history of declining empires. Imperial powers don’t like decline, just ask the British and the French! Thus, when the Russian/Soviet empire, the largest remaining European empire, just vanished away in three years, we should not have assumed that was the end of the story. We should have suspected that the empire might strike back.

Garton Ash gleaned a hint of things to come when in 1994 he met Putin, then a totally unknown “side-kick” of the mayor of St Petersburg. At the end of a two-day conference, Putin broke his silence and said that “we have to remember that there are territories outside the Russian Federation that have historically always been Russian and the Russian Federation has a duty towards them.” He specifically mentioned Crimea.

Thus, the West should have been alert to Russia’s revanchist instincts as early as the time of the Transnistria conflict and the first Chechen War, both of which occurred well before the first post-Cold War expansion of NATO (in 1999), something which is often blamed for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Garton Ash believes that we should have gone full-speed ahead for Ukraine’s NATO membership at the Bucharest summit in 2008.

It was a mistake by Chancellor Angela Merkel to block it, after Putin had virtually declared war on the West at the 2007 Munich security conference. In contrast to many analysts, Garten Ash believes that there was no lack of efforts to integrate Russia into the global community. The problem was always on the Russian side.

Garten Ash insists that Ukraine must win the current war, and that the West must do more to ensure that victory. Then Europe’s great strategic objective for the next decade should be another great step towards Europe whole and free. Both the EU and NATO must be expanded to include Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and Southeast Europe. This is the only way to create a stable European security order and secure these countries against a dangerous Russia.

But this will require leaders of the calibre who brought the Cold War to an end, notably George H. W. Bush and Helmut Kohl. As Europe’s biggest and central nation, Germany will have to drop its reticence and play a leadership role, especially in the elaboration of a “Marshall Plan for Ukraine.” At this stage, however, the EU’s central European members are all fired up for this, but the West Europeans are not, especially in light of anti-immigration sentiments in many countries.

Garton Ash is rather unique as a British professor/journalist who believes in Europe with his heart and soul. As an historian of the present, he is able to offer deep insights into “the lived experience” of Europe. Some may criticise his writing for being too anecdotal. But for this reader, Garton Ash offers a very engaging portrait of Europe through his “personal” history, which is very much about the role of people, both leaders and ordinary, in Europe’s history.

This review of Homelands: A Personal History of Europe by Timothy Garton Ash was published by the Australian Institute for International Affairs.

John West is adjunct professor at Tokyo’s Sophia University and executive director of the Asian Century Institute. His recent book “Asian Century … on a Knife-Edge” was reviewed in Australian Outlook.