Anyone parenting young children will be familiar with the phrase “there’ll be tears before bedtime”. But in a quieter, more private way, the expression seems perfectly pitched to describe the largely hidden grief of ageing.

Not the sharp grief that follows a bereavement (though bereavements do accumulate with the years), but a more elusive emotion. One that is, perhaps, closest to the bone-gnawing sorrow of homesickness.

Sarah Manguso evokes this sense of having travelled further from our younger selves than we could ever have imagined:

“Sometimes I feel a twinge, a memory of youthful promise, and wonder how I got here, of all the places I could have got to.”

Historically, the phenomenon of homesickness was identified in 1688 by the Swiss medical student Johannes Hofer, who named it nostalgia from the Greek nostos, meaning homecoming, and algos, meaning an ache, pain, grief and distress.

It was the disease of soldiers, sailors, convicts and slaves. And it was particularly associated with soldiers of the Swiss army, who served as mercenaries and among whom it was said that a well-known milking song could bring on a fatal longing. (So singing or playing that song was made punishable by death.) Bagpipes stirred the same debilitating nostalgia in Scottish soldiers.

Deaths from homesickness were recorded, but the only effective treatment was to send the afflicted person back to wherever they belonged.

The nostalgia associated with old age, if it occurs, appears incurable, since there can be no possibility of a return to an irrecoverable youth. But as with homesickness, how badly those afflicted suffer seems to depend on how they manage their relationship with the past.

The phantom was me

American writer Cheryl Strayed describes deciding to transcribe her old journals. On reading one of them from cover to cover, she is left feeling

“kind of sick for the rest of the day, as if I’d been visited by a phantom who both buoyed and scared the bejesus out of me. And the weirdest of all is that phantom was me! Did I even know her anymore? Where did the woman who’d written those words go? How did she become me?”

I’ve experienced a similar rush of bafflement and grief upon opening a letter I’d written some time before I turned 50. My mother had saved it and returned it to me 20 years later. Within its pages I found a younger, more energetic and vibrant self. The realisation this woman who inhabited the letter so vividly was no longer available to me came with a jolt of emotion that felt like a bereavement.

I was so knocked off-kilter by this ghost-like encounter that the letter (along with others I had been planning to transcribe) had to be set aside for a day when I might be able to muster the necessary courage and detachment. Whether that day ever comes will depend, I suppose, on how I navigate my own relationship with time, and on reaching a calm acceptance of the distance travelled.

Disbelief at the distance between the young self and the old self is one of the factors in this late-life grieving. At its root, perhaps, is an internalised ageism: innate, or else massaged into us by the culture we spring from.

In a series of recent conversations with people over 70, I encouraged them to tell their stories and to reflect on the effects of time on their lives. Childhood sometimes emerged as a place they were pleased to have left behind – and occasionally, as a place to be held close.

Trevor emigrated alone to Australia when he was just 18. I asked him how often now, at 75, he thinks about his childhood. “Do you have a sense of who you were back then, and is that person still part of who you are?”

“I think about my childhood quite a lot, especially putting some distance between where I was then and where I am now,” he told me. “I didn’t have a really happy upbringing, and coming to Australia was a way of getting away from home and experiencing a new culture.”

In response to the same question, Jo, at 84, led me to a framed photograph, enlarged to poster-size, which has hung on the wall of both his homes. It shows him aged three, in a garden – a radiant child wearing a plain white shirt and dark shorts, arms out-flung as if to embrace the natural world. He bursts with exuberance, curiosity, and joy.

“I relate to that as an idea, as a concept of my life. I want to maintain that freshness, that child-like freshness. You’ve got no responsibilities; every day is a new day. You’re looking at things in a different light, you’re aware of everything around you. That’s what I wanted to maintain, that feeling through my life – I’m talking age-wise. My concept of my ageing is there in that photograph.“

While older voices are often absent in the media, and in fiction they are too often presented as stereotypes, in conversation what arises can both surprise and inspire.

‘How can I be old?’

As I approached my own 70th birthday, I realised I was about to cross a border. Once I was on the other side, I would be old – no question. Yet the word “old”, especially when coupled with the word “woman”, is carefully avoided in our culture. Old is a country no one wants to visit.

Penelope Lively’s novella-length story Metamorphosis, or the Elephant’s Foot, written when Lively was in her mid-eighties, explores this evolution from youth to old age through the character of Harriet Mayfield. As a nine-year-old, Harriet is reprimanded by her mother for not behaving well on a visit to her great-grandmother.

“She’s old,” says Harriet. “I don’t like old.”

When her mother points out that one day Harriet, too, will be old, like her great-grandmother, Harriet laughs.

“No, I won’t. You’re just being silly,” says Harriet “how can I be old? I’m me.”

Towards the end of the story, Harriet is 82 and must somehow accept that she is “in the departure lounge. Check-in was a very long time ago.” With her equally elderly husband, Charles, Harriet ponders what they can do with the time remaining. Charles decides “it’s a question of resources. What do we have that could be used – exploited?” Harriet replies, “Experience. That’s it. A whole bank of experience.”

“And experience is versatile stuff. Comes in all shapes and sizes. Personal. Collective. Well, then?”

If distance travelled is a factor in late-life grief, so too is a sense of paths not taken: of a younger self, or selves, that never found expression.

In Jessica Au’s recent, much-awarded novella Cold Enough For Snow, there is a scene where the narrator explains to her mother the existence, in some old paintings, of a pentimento – an earlier image of something the artist had decided to paint over. “Sometimes, these were as small as an object, or a colour that had been changed, but other times, they could be as significant as a whole figure.”

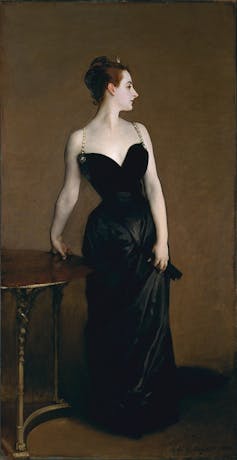

Madame Pierre Gautreau by John Singer Sargent.

Art historians, using X-rays and infrared reflectography, have identified pentimenti in many famous paintings, from the adjusted placement of a controversial off-the-shoulder strap in John Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Madam X, to the painted-over figure of a woman nursing a child in Picasso’s The Old Guitarist, and a man with a bow-tie concealed beneath the brushwork of his work The Blue Room.

Singer Seargent’s adjustment was his response to an outcry at the perceived indecency of Madame X’s lowered shoulder strap, which both the public and art critics of the time declared to be indecent. By contrast, the model’s icy pallor caused only a ripple of interest.

Picasso’s hidden figures are assumed to be the outcome of a shortage of canvas during his Blue Period, but shortages aside, the word pentimento, which derives from the Italian verb pentirsi, meaning “to repent”, brings to these lost figures a sense of regret that resonates with the feeling in old age of having lost the younger self, or of carrying traces, deeply buried, of other lives one might have lived.

In Cold Enough for Snow, Au’s narrator remarks of her mother that

“Perhaps, over time, she found the past harder and harder to evoke, especially with no-one to remember it with.”

The mother’s situation references another source of grief: that of the person who becomes the last of their friends and family still standing.

In childhood games of this nature there would be a prize for the survivor. But for those who reach an extreme old age, having lost parents, siblings and contemporaries who knew them when they were young, even the presence of children and grandchildren may not entirely erase this “last man standing” loneliness. There is, too, the darkness of a projected future where there is no one still living who remembers us.

In Jessica Au’s book the narrator occasionally speaks of the past as “a time that didn’t really exist at all”. And yet in my recent conversations with people in their seventies and above, every one of them admits to feeling a vivid sense of the past, and of the continuing presence of a younger self. As one of them wistfully remarked: “Sometimes she even seeps through.”

Memory and detail

Perhaps part of the problem is the mass of ordinary detail that disappears from memory on any given day. Life is made up of so many small moments that it’s impossible to hold onto them all – and if we did it might even be damaging.

Imagine someone casually asking how your day had been, and responding with the tsunami of detail those hours actually contained.

After opening your eyes at first light, you’d describe your shower, your breakfast, and how you slipped your keys into your handbag as you left the house; in the street you’d passed two women with a pram, a child with a small white dog on a lead, and an elderly man with a walking stick. And so on.

If our minds swarmed with the trivia of daily life, more important events might be forgotten, and possibly the neural overload would even make us ill. Yet with the realisation of the loss of these minutes and hours arises the anxiety that in time, the things we do want to remember will slither away from us into the dark.

I imagine this fear is what compels people to fill social media with photographs of their breakfasts, and of their relentless selfie-taking. It is surely the impulse behind keeping a journal.

The anxiety of losing even the passing moments in a day afflicts the author of Ongoingness: The End of a Diary. In it, the American writer Sara Manguso describes her compulsive need to document and hold onto her life. “I didn’t want to lose anything. That was my main problem.”

After 25 years of paying attention to the smallest moments, Manguso’s diary is 800,000 words long. “The diary was my defense against waking up at the end of my life and realizing I’d missed it.” But despite her continuous effort,

“I knew I couldn’t replicate my whole life in language. I knew that most of it would follow my body into oblivion.”

Is it possible that women experience grief around ageing earlier, and more emphatically than men? After all, by the age of 50, the bodies of even those women who remain fit send the implacable signal that things have changed.

In Alice Munro’s story Bardon Bus, from her collection The Moons of Jupiter, the female narrator endures dinner in the company of a rather malicious man, Dennis, who explains that women are

“forced to live in the world of loss and death! Oh, I know, there’s face-lifting, but how does that really help? The uterus dries up. The vagina dries up.”

Dennis compares the opportunities open to men as opposed to those available to women.

“Specifically, with ageing. Look at you. Think of the way your life would be, if you were a man. The choices you would have. I mean sexual choices. You could start all over. Men do.”

When the narrator responds cheerfully that she might resist starting over, even if it were possible, Dennis is quick to retort:

“That’s it, that’s just it, though, you don’t get the opportunity! You’re a woman and life only goes in one direction for a woman.”

In another story in the same collection, Labor Day Dinner, Roberta is in the bedroom dressing for an evening out when her lover George comes in and cruelly remarks: “Your armpits are flabby.” Roberta says she will wear something with sleeves, but in her head she hears the

“harsh satisfaction in his voice. The satisfaction of airing disgust. He is disgusted by her aging body. That could have been foreseen.”

Roberta thinks bitterly that she has always sought to remedy the least sign of deterioration.

“Flabby armpits – how can you exercise the armpits? What is to be done? Now the payment is due, and what for? For vanity. Hardly even for that. Just for having those pleasing surfaces once, and letting them speak for you; just for allowing an arrangement of hair and shoulders and breasts to have its effect. You don’t stop in time, don’t know what to do instead; you lay yourself open to humiliation. So thinks Roberta, with self-pity […] She must get away, live alone, wear sleeves.”

As with most emotions that arise around our ageing, it can usually be traced back to a fraught relationship with time. French philosopher and Nobel Prize winner Henri Bergson says: “Sorrow begins by being nothing more than a facing towards the past.”

For Roberta, as for many of us, it was a past in which we relied on those “pleasing surfaces”, perhaps even took them for granted, until they no longer produced the desired effect.

But the truth is that our bodies are capable of more severe betrayals than mere flabby armpits. In time they may cause us to be exposed in skimpy, front-opening or back-opening hospital gowns under the all-seeing eye of the CT scanner; they may deliver us into the skilled, ruthless hands of a surgeon. Our very blood may speak of things we will not wish to hear.

Middle Age and Mortality

Middle age is sometimes referred to as The Age of Grief. It’s when we first glimpse our own mortality; we feel youth slipping away into the past, and the young people in our lives begin to assert their independence.

We have our mid-life crises then. We join gyms, and take up running; we speak for the first time of “bucket lists” – the term itself an attempt to diminish the sting of time’s depredations. None of this will save us from the real Age of Grief, which comes later and hits harder because it is largely hidden. And we’ll be expected to endure it in silence.

In my conversations with people aged 70 and older, grief has surfaced from causes other than what might be called “cosmetic” changes. Following a severe stroke, 80-year-old Philippa describes the pain of having had to make the decision to relinquish her home and move into residential care.

“It’s when you lose your garden, which you’ve loved, and you’ve got to walk away from that. I’ve got photos of the house, and I look at them and think, oh, I just love the way I did that room, decorated it, things like that. But change happens.”

“Somehow change always comes with loss, as well as bringing something new,” I said. “Yes,” she replied, “I just had to say to myself: you can’t worry about it, and you can’t change it. That sounds hard, but it’s my way of dealing with it.”

Tucked away in residential care homes, largely invisible to those of us lucky enough to still inhabit the outside world, elderly people like Philippa are quietly raising resilience to the level of an art form.

In her poem, One Art, the Canadian poet Elizabeth Bishop advises losing something every day.

“Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

Lose something every day.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.”

Bishop goes on to list other lost items – her mother’s watch, the next-to-last of three loved houses, lovely cities, two rivers, even a continent. While the losses elderly people commonly accumulate are less grand, they are no less devastating.

One by one, they will relinquish driver’s licenses. For many there will be the loss of the family home and their belongings, save for whatever will fit into a care home’s single room. Perhaps they have already given up the freedom of walking without the aid of a stick, or walker. There may be the dietary restrictions imposed by conditions such as diabetes, and the invisible disabilities of diminished hearing and eyesight.

A failing memory, one would think, must be the final straw. And yet, what seems to be the actual final straw is the situation, reported time and again, where an old person feels “unseen”, or “looked through”, and for indefensible reasons finds themself being “missed” in favour of someone younger. It might, for example, be a moment when they are ignored as they patiently wait their turn at a shop counter.

In my conversation with Philippa, she remarked that old people are often looked through when they are part of a group, or when they are waiting to be served. “I have seen it happen to other older people, as if they don’t exist. I have called out assistants who have done that to other people.”

Surely the least we can do, as fortunate beings of fewer years, is to acknowledge the old people among us. To make them feel seen, and of equal value.

‘Age pride’ and destigmatising ‘old’

Ageism, Healthy Life Expectancy and Population Ageing: How Are They Related is a recent survey conducted with more than 83,000 participants from 57 countries. It found that ageism negatively impacts the health of older adults. In the United States, people with a negative attitude towards ageing live 7.5 fewer years than their more positive counterparts.

In Australia, the National Ageing Research Institute has developed an Age-Positive Language Guide as part of its strategy to combat ageism.

Examples of poor descriptive language include terms such as “old person”, “the elderly”, and even “seniors”. That last term appears on a card Australians receive shortly after turning 60, which enables them to receive various discounts and concessions. Instead, we are encouraged to use “older person”, or “older people”. But this is just another form of age-masking that fools no one.

It would be better to throw the institute’s energy into destigmatising the word “old”. What, after all, is wrong with being old, and saying so?

To begin the process of reclaiming this word from the pejorative territory it currently occupies, old people need to start claiming their years with pride. If other marginalised social groups can do it, why can’t old people? Some activists working against ageism are beginning to mention “age pride”.

If we become homesick for who we once were as we age, we might remind ourselves of the meaning of nostos and consider old age as a kind of homecoming.

Narrative identity

The body we travel in is a vehicle for all the iterations of the self, and the position we currently inhabit is part of an ongoing creative process: the evolving story of the self. From the 1980s, psychologists, philosophers and social theorists have been calling it narrative identity.

The process of piecing together a narrative identity begins in late adolescence and evolves across our entire lives. Like opening a Russian doll, from whose hollow shell other dolls emerge, at our centre is a solid core composed of traits and values. It’s also composed of the narrative identity we have put together from all our days – including those we cannot now remember – and from all the selves we have ever been. Perhaps even from the selves we might have been, but chose instead to paint over.

In Metamorphosis, or the Elephant’s Foot, Harriet Mayfield tells her husband, “At this point in life. We are who we are – the outcome of various other incarnations.”

We know our lives, and the lives of others, through fragments. Fragments are all we have. They’re all we’ll ever have. We live in moments, not always in chronological order. But narrative identity helps us make meaning of life. And the vantage point of old age offers the longest view.

The story of the self carries us from the deep past to the present moment. And old age sets us the great life challenge of maintaining balance in the present, while managing the remembered past – with all its joys and griefs – and the joys and griefs of the imagined future.

This article was published by The Conversation.