Narrowing the trust divide

The Trust Divide defines the gap between voters’ expectations of, and satisfaction with, the performance of politicians and government institutions. It is held as axiomatic that the narrower the Divide, the healthier the democracy; because trust is absolutely crucial to a government’s ability to govern effectively.(1)

It is concerning, however, to track the decline in trust in Australia over just ten years. In 2007, 86% of citizens were satisfied with the way their democracy was working,(2) but by 2017 that had dropped to 41%.(3)

This is not to suggest that democracy is broken nor that it has reached an end-state. And, although democracy is under pressure, it does contain the seeds of its own resurgence.(4) Not the least because 74% of Australians still believe that democracy is preferable to any other kind of government.(5)

It is considered, however, that any recovery will be dependent on narrowing the Trust Divide between voter dissatisfaction and the self-satisfaction of elected parliamentarians.

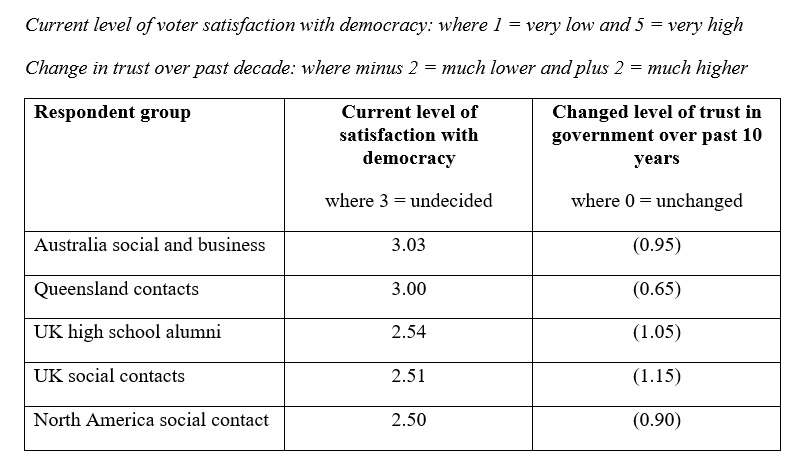

In this context, dissertation research sought to quantify satisfaction with the state of democracy today and confirm the extent to which trust in politics and government institutions has declined over the past decade. A first round of research involved face-to-face, Zoom and mobile phone interviews with Australian politicians (n=23); followed by an initial on-line voter survey of urban contacts across the Anglosphere (Australia, UK and USA) (n=151), and of rural Queenslanders (n=37).

Survey results suggest that low levels of voter satisfaction with democracy and declining levels of trust in government over the past decade should give all politicians considerable pause for thought.

Survey Feedback

Survey respondents also made over 500 suggestions for political and institutional reforms aimed at narrowing the Trust Divide. A follow-up survey requested scoring (by Importance and Implementability) of 20 reform initiatives derived from the 500 suggestions. These reform initiatives were focused on building the operational efficiency and resilience of democracy. Scoring against Importance and Implementability by Australian participants allowed for a relative positioning of reform initiatives on the Reform Matrix following.

Reform proposals made by voter survey respondents, their broad coincidence with open-ended responses from Australian politicians, and their scoring for Importance and Implementability are not a menu of solutions. Rather, they are a pointer for thinking by political parties seeking to re-engage with an increasingly untrusting and dissatisfied public.

Despite some differences, it is worth noting that Australian and British respondents both place high emphasis (Implement & Maintain) (see top right quadrant in matrix) on the need for anti-corruption initiatives, greater transparency on donations and the enhanced facilitation of voting.

Country-to-country coincidence on reforms with applicability to the medium terms (Rebuild Trust) (bottom right quadrant) included limitations on lobbyist access, the requirement for truth in political advertising (TPA), the need for greater transparency in policy decision-making, and on slowing the revolving door in post-ministerial careers.

Regional devolution, education in politics, citizen participation, stricter candidate selection criteria, electoral system reform (RES) and quotas were all acknowledged as being longer-term issues (Fortify the Institutions) (bottom left quadrant).

Respondent groups amplified the importance of integrity and independence within government institutions responsible for enforcing codes of conduct, dealing with corrupt behaviour, managing elections, tracking donations, curtailing the influence of lobbyists, as well as managing the performance and behaviour of parliamentarians.

Australian Reform Matrix

Australian politicians highlighted some of the same reforms. Although the sample was small (n=7 out of 23), politicians did assign high scores to the Importance of: extending parliamentary terms (scoring 4.6 out 5); establishing (what is now) the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) (4.4); requiring more significant control over, and real-time reporting on, donations (4.3); retaining compulsory voting (4.3); and requiring education in politics and ethics during the final two years at all high school (4.0).

The widest gaps between politicians and voters in scoring for Importance were on the need for better access to voting (digital voting), the level of attention to be paid to the future (climate change), support for legislation on truth in political advertising, and better control over the revolving door in post-ministerial careers. All were scored high by voters and low by politicians.

It is acknowledged that Australia’s current Labor government has committed to rectifying board stacking at the ABC and the AAT, and has established the NACC. It has also signalled possible changes that would require truth in political advertising, place caps on campaign contributions and enforce tougher disclosure provisions on the sources of campaigns donations. Important reform proposals have also been put forward by the recent joint standing committee on electoral matters.(6) Some progress is being made.

Regardless, the starting hypothesis stands: that the decline in trust and widening of the Trust Divide are evident and pose genuine risks to liberal democracies. Research confirms that voters, academics and many politicians all acknowledge this reality and agree that much must be done to rectify some of democracy’s more apparent flaws.

If liberal democracy is to overcome its current tribulations, it is advised that reforms focus on rebuilding the strength and independence of government institutions at the heart of democracy, and that the necessary reforms be introduced within the short term.

However, until our politicians acknowledge that re-election prospects are, at least in part, dependent on closing the Trust Divide between themselves and the electorate and on the continued independence of those institutions that underpin democracy, the risks of sliding into ‘illiberalism’ remain.

References

1. Baxter, J. (2021), “Why this government may never regain the trust of the people“, LSE British Politics and Policy online, 15 January 2021

2. Bean, C., Gow, D. and McAllister, I. (2017), Australian Election Study 2007, ADA Dataverse Vol 1, 27 October 2017

3. Evans, M., Stoker, G. and Halupka, M. (2019), Democracy 2025 Report No 5 – How Australian Federal Politicians Would Like to Reform Their Democracy, Canberra: Museum of Australian Democracy

4. Levitsky, S. and Way, L. (2016), The Myth of Democratic Recession, Chapter 4 in Diamond and Plattner (eds), 58-76, Democracy in Decline! Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

5. Kassam, N. (2022), Lowy Institute Poll 2022, Lowy Institute

6. Massola, J. and Wright, S. (2023), ‘Parliament needs 49 extra MPs’, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 November 2023

After retirement, Fergus Neilson returned to postgraduate study at University College London. He was awarded an MSc in Political Science (Democracy and Comparative Politics) in November 2022. His dissertation was awarded “with distinction”. This blogpost is an edited version of that dissertation. See full item in the Journal of Behavioural Economics and Social Systems Vol5, No1/2.

Fergus Neilson has a wide range of business and life skills gathered from a career in the armed forces, investment banking, the United Nations, McKinsey & Company and private equity investment.