Disagreeing where we must

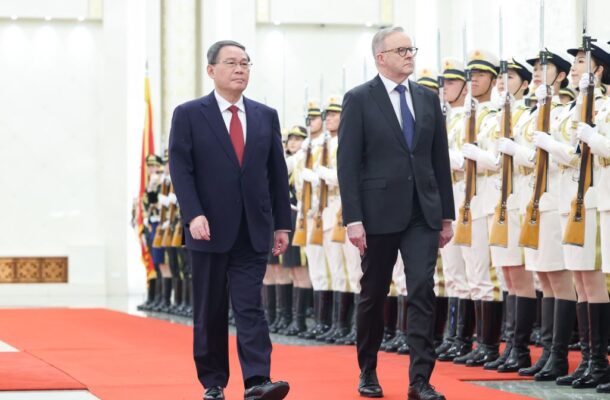

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit last week to the People’s Republic of China was a reminder that beyond the metrics of trade and the mechanics of statecraft, the Australia–China relationship carries deep meaning in Australia’s national life.

When Canberra established formal diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1972 amid the transformative politics of the period, Australia’s relationship with China became a metaphor for one version of a national story told as waking to a modern, independent, forward-looking Australia that could finally see its future in the region. It also defined relations with Britain and the US as the legacy of Australia’s colonial past.

As a metaphor for a modern Australia, the China relationship has animated national life for decades. It aligned well with the post–Cold War era of globalisation when trade and investment were driving Australian policymaking generally, reaching a highpoint in the boosterism of the 2010s. With the signing of the China–Australia Free Trade Agreement in 2014, Australia’s trade minister declared that China would secure the nation’s future for ‘50 to 100 years’.

The metaphor also worked when China itself was relatively more liberal in the 2000s. It was easier for governments, businesses and public institutions in Australia to set aside the realities of China’s party-state system and make the case for a China future by focusing on the social, cultural and economic dynamism of China’s development.

Both the Chinese and Australian sides leaned heavily into that meaning to give salience to Albanese’s visit. It was framed around the 50th anniversary of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s visit in 1973 and even included a photo op at the Temple of Heaven to hark back to the iconic image of Whitlam leaning against the Whispering Wall.

But as the debate surrounding the visit has shown, the China metaphor has become a source of tension in the policy and politics of Australia’s responses to China as the Xi Jinping era has deepened.

It frames the securitisation of relations through issues such as foreign interference and the AUKUS agreement as retrograde rather than a response to Beijing’s hardening politics. It has radicalised public institutions as their reluctance to recognise the reassertion of the Chinese Communist Party’s totalitarianism is required to be ever more zealous. And its economic case has been hollowed out by Beijing’s trade sanctions and China’s own economic problems.

A national future that Australia might have imagined for itself with China has become divisive and disruptive as that future has taken the form of Xi’s vision.

In recognition of these issues, the Albanese government has adopted a formula to manage China relations, which is: ‘We will cooperate where we can, disagree where we must and engage in the national interest.’

This structures the relationship into a balance of different conceptual domains. It is stabilising because its recitation means neither one nor the other of ‘cooperation’ or ‘disagreement’ can come to define the relationship by itself, and it lands on the concept of the national interest, the value of which comes from what it is not, which is corporate interests in a commodity trade-dominated economy, so reasserting the importance of sovereignty and statehood.

But the formulation leaves unanswered the questions of what exactly Australia should be cooperating on and disagreeing about. It offers a useful policy typology but it is not a metaphor for Australia’s future with China that can propel policy, politics and national life. Without those answers, it risks becoming a way of avoiding disagreements and leaving Australia stuck in a pattern of reactive relationship management that makes it harder to chart a course for the nation.

In other words, by identifying the fundamental areas of disagreement, Australia can have a clearer sense of its national future in the Xi era.

Needless to say, the most fundamental area of disagreement is China’s and Australia’s relationships with Taiwan. As Beijing declares often, the status of Taiwan is an existential issue at the core of the ideology and purpose of the party-state system. It is the object of relentless military, political and diplomatic tactics to take China closer to what it calls ‘reunification’.

Canberra well understands the devastating effects a war against Taiwan would have on Australia’s economy and security. Australian governments have made numerous statements in recent years on the importance of peace across the Taiwan Strait and no unilateral change in the status quo.

But Taiwan has also always been the supplemental part of Australia’s China metaphor. Just as establishing relations with Beijing in 1972 became an emphatic statement about Australia’s future in the region, so too was the punitive severing of relations with Taipei. Since then, Australia–Taiwan ties have moved gradually forward in the absence of diplomatic recognition to become an important trade relationship with rich and meaningful cultural and community links. But that has occurred against the tide of an Australia–China relationship that was implicitly premised on the position that the Taiwanese people were on the wrong side of history.

The national-interest case for maintaining peace across the Taiwan Strait is self-evident. But to acknowledge that Australia could disagree with Beijing on its vision for Taiwan’s future as a province of the People’s Republic of China and see meaning for the Australia–Taiwan relationship itself recognises that treating China as a metaphor rather than a real place hasn’t offered a stable context to policy or an enduring way to tell Australia’s modern story.

Canberra could support Taiwan’s membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or a free-trade agreement in Australia’s own trade interests. It could strengthen defence cooperation to be properly prepared for a crisis in the Taiwan Strait. But a first step would be for the government to acknowledge that it is Beijing that threatens Taiwan militarily and diplomatically and shift its phraseology to: ‘Australia opposes any changes by Beijing to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait.’ This is a statement of the kind of region in which Australia wants to into the future and an animating metaphor for the politics and policies needed to sustain it.

This article was published by The Strategist.

Open Forum is a policy discussion website produced by Global Access Partners – Australia’s Institute for Active Policy. We welcome contributions and invite you to submit a blog to the editor and follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin and Mastadon.