For the better part of two years between 2006 and 2008, Jeffrey Walker spent every spare minute in his backyard shed, and sometimes even his living room, hunkered down surrounded by bibs and bobs of metal sheeting and neat little piles of shiny rivets, painstakingly piecing together a one-of-a kind jigsaw puzzle.

He was building his own aeroplane.

“The kids sometimes helped. I’ve got pictures of them putting rivets in the holes,” he says, adding reassuringly that he always double-checked their handiwork.

Despite the family enthusiasm for the project, the modified Van’s RV-10 four-seater fixed-wing plane wasn’t for joy flights.

In fact, it was the next step in the esteemed academic’s relentless search to find new and better ways to measure the Earth’s soil moisture; a stepping stone to space by simulating new satellite missions and developing more accurate data to forecast weather and changes in our climate.

“I figured the University wasn’t going to buy me a plane, so I took the money out of my savings and built it myself, and every spare minute I had went into putting it together, then learning how to fly it,” he says.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that an engineer with such galactic vision is now a finalist in the coveted Australian Space Awards 2022, recognition for a career pushing the boundaries of space to pioneer the critical ways we measure our planet’s health.

“The space industry is vital to a globally sustainable future, so I’m honoured to receive the recognition of being a finalist,” says the head of Civil Engineering at Monash University.

“Some people think about space in terms of walking on the Moon or what happens on Mars; my interest is using space to see what happens on Earth. Harnessing what space can do to better-understand and take care of our own planet, because observing Earth is the most important thing we can do.”

From Taree to NASA

Walking the corridors of places such as NASA and the European Space Agency never crossed the young Jeffrey Walker’s mind when he was tinkering with his dad in the garage of their Taree home, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales.

“My parents didn’t finish high school. My dad was a welder, then drove taxis and did all sorts of jobs between retrenchments, while my mum sold Avon door-to-door to make ends meet.

“University wasn’t on my radar, but I clearly remember the prime minister of the day, John Howard, encouraging kids to finish Year 12 instead of leaving school in Year 10, and that resonated with me, so I thought I’d stay and see where it took me.”

While the thought of going to university was “totally foreign” to Jeffrey, he found his feet during work experience at a local surveying and civil engineering firm, and was encouraged to continue his education and consider a career in the field.

In 1996, he graduated from the University of Newcastle with a double degree, BEng (Civil) and BSurv, then pursued a PhD in pioneering methods of how to use soil moisture data should it become available from satellites. It led to an opportunity to further his PhD work at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre at Greenbelt, in the US.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre at Greenbelt in the US.

“I’d never been on a plane, let alone out of the country, so this was beyond my wildest dreams,” he says.

“In many ways, working at NASA was just like being at a university, except that in the building next door you could watch the next satellite being built, and that was very exciting.”

While at NASA he not only implemented his PhD thesis work for integrating satellite observations of soil moisture with numerical land surface prediction models globally, but also co-created the first global satellite-based soil moisture maps from the available sensors of the day.

Professor Walker’s time at NASA was the beginning of a decorated career in space-related engineering research. He has literally broken new ground with technology to measure the Earth’s soil moisture, and his handmade kit-plane was integral to this success.

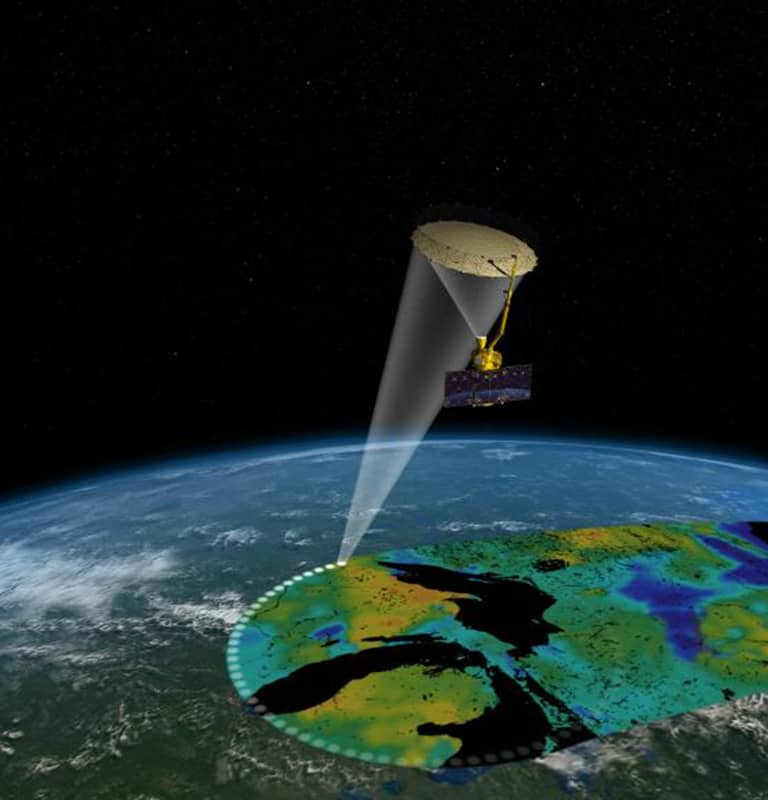

Artist’s rendering of the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite.

His expertise and technical capability has been called upon by the European Space Agency and NASA, where he was involved with developing and validating the algorithms for both the SMOS and SMAP satellites for global soil moisture mapping.

Most recently, he’s led ARC-funded research efforts to create a world-first capability that combines radar and radiometer data at two different frequencies (known as P and L Band data), which simulates a potential future satellite soil moisture missions.

“My work has shifted a lot over the years. In the early days it was about working out if we could use measurements of soil moisture to improve hydrologic predictions, then it became about developing the tools to make the necessary soil moisture observations. If I couldn’t find the tool I needed to do my work, I set about making it.”

Throughout his two decades in academia, Professor Walker has secured $34 million of research funding, enabling international collaboration on large-scale projects, but even still, much of his work has been done on the smell of an oily rag.

“When opportunities present themselves, I take them with both hands and run as fast as I can. I like to lead ideas and make change, push boundaries, and not just follow – and I’ve done that by creating infrastructure that nobody else has.”

For Professor Walker, space innovation plays a crucial role in monitoring the health of our planet, and he’s hopeful that future investment in space technology will support research much closer to home.

“There’s huge potential to grow Australia’s space industry. Earth is the most important planet of the solar system, as it’s the one we live on, and if we don’t look after it, we will kill it.”

This article was published by Lens.